Table of Contents

Supreme Court justices don’t line up politically on free speech — and that’s a good thing

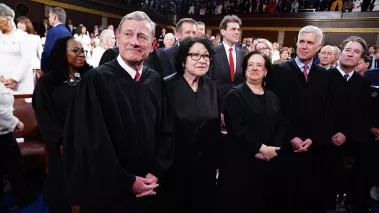

SHAWN THEW / Pool via USA TODAY NETWORK

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Roberts (front) — along with Associate Justices (left to right) Ketanji Brown Jackson, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh — ahead of the 2024 State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress.

The American people’s trust in the United States Supreme Court is low. The public increasingly sees the court’s decisions as political and the media often portrays rulings in terms of which president appointed each justice. One might expect First Amendment cases to follow suit.

But they don’t — and that’s a good thing.

Despite the widely covered, ideologically divisive 6-3 cases, Supreme Court justices agree with one another most of the time. As Sarah Isgur and Dean Jens have argued, Supreme Court justices fall into three camps that predict most of their non-unanimous rulings. There are the liberals (Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Jackson), the conservative “high institutionalists” (John Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett), and the conservative “low institutionalists” (Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch). The two conservative groups differ in their willingness to overturn precedent.

In non-unanimous cases, the six conservative justices only voted together 17% of the time. Sotomayor, the most liberal justice, voted with Alito, the most conservative justice, 63% of the time. Kavanaugh voted 80% of the time with both liberal Jackson and “low institutionalist” Alito. That said, justices agreed with members of their own group more than 90% of the time.

But First Amendment cases do not follow this trend. Of the 18 First Amendment decisions in the last three terms, 11 were unanimous. And even in difficult First Amendment cases that do not produce a unanimous ruling, the justices do not always conform to their ideological grouping. Of the seven decisions that were not unanimous, only three saw each group vote as a bloc. Of those three, only two pitted the six conservative justices against the three liberals.

The 8 First Amendment cases the Supreme Court will decide this term

News

The Supreme Court is poised to decide cases determining online speech rights and when government ‘jawboning’ crosses a constitutional line.

This is remarkable because First Amendment issues present the justices with potentially divisive issues. Take Twitter v. Taamneh, where the Court held that social media platforms are not liable for terrorism even if certain content radicalizes people to become terrorists. Despite the socially charged underlying facts, the decision was unanimous.

In Counterman v. Colorado, the state prosecuted a man for stalking a woman online, but the Court said Colorado must prove he had a “subjective understanding” that his comments were threatening. One might assume the liberal justices would vote to uphold the conviction. But Justice Kagan wrote the court’s opinion, with Justice Thomas and Justice Barrett dissenting.

Or take Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, which saw unusual groupings of justices fight over the scope of the fair-use defense against copyright infringement. The Court held that Andy Warhol’s depictions of Prince are not protected by fair use. Justice Sotomayor wrote the Court’s opinion and was joined by Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Jackson. Gorsuch and Jackson concurred, arguing for a narrow reading of the holding. But Justice Kagan and the chief justice joined in a scathing dissent, in which Kagan contended that her fellow liberal Sotomayor was “indifferent” to the First Amendment.

Finally, the Court’s recent decision in National Rifle Association of America v. Vullo saw all nine justices unite around the clear First Amendment principle that the government cannot punish groups based on ideology. Although the speech at issue was the NRA’s pro-gun advocacy, a conservative cause, Justice Sotomayor authored the majority opinion.

The Court must continue to impartially assess the government’s power to censor or compel speech regardless of the content of that speech. If we stray from this task, the First Amendment will hold no weight.

This lack of predictability is good for the country. Unanimous rulings and idiosyncratic voting alignments indicate that the justices consider the merits of each case rather than the messages of the speakers. Imagine if instead, today’s conservative Court only protected conservative speakers.

The Roberts Court has generally kept America from allowing, as Justice Antonin Scalia once opined, one side to fight “freestyle” while subjecting the other to “Marquis of Queensberry rules.” From banning flag burning to kicking someone out of a public legislative gallery for wearing a shirt with a disfavored political slogan, the government will always try to regulate disfavored views — or ban them outright. If the justices simply rubber-stamp every policy that censors speech with which they disagree and overturn every policy that does the opposite, the First Amendment will lose all meaning.

A turning point for First Amendment methodology?

Although agreement and idiosyncratic voting are still the norm in First Amendment cases, some methods of constitutional interpretation allow justices to smuggle their own ideological predispositions into First Amendment cases. In a few recent cases, the cracks have shown.

In Vidal v. Elster, the Court unanimously held that the Lanham Act’s names clause does not violate the First Amendment. That clause requires trademark applicants to get consent before trademarking someone’s name. Five conservative justices argued for a “history and tradition” approach to such cases, but they couldn’t agree on how it applies. Justices Barrett and Sotomayor called for a standard based on precedent. Barrett wrote against following “pedigree rather than principle” while Sotomayor said the majority “found its friends in a crowded party to which it was not invited,” meaning it had injected historical analysis where no one had requested it.

Looking to history — even when a precise historical analogue exists — reframes First Amendment rights as a historical privilege that courts dole out in the proper context rather than framing free speech as a fundamental right. Plus, as Justice Sotomayor points out, lawyers are not historians, so disagreements about historical interpretation can too easily become proxies for ideological disputes.

Already some justices are beginning to veer away from the Court’s staunch defense of free speech. In 303 Creative v. Elenis, the Court ruled 6-3 on a conservative-liberal split in favor of a website designer who violated Colorado’s anti-discrimination statute by refusing to make websites for same-sex weddings. Writing for the majority, Justice Gorsuch said the First Amendment protects speech regardless of content, adding that under the dissent’s view, the government could compel a Muslim director to produce a Zionist film. He left the lower courts with the neutral principle that states cannot force designers to “create expressive designs” containing messages with which they disagree, thus protecting liberal and conservative artists alike.

Breaking with Gorsuch and her Vidal concurrence, Justice Sotomayor failed to follow First Amendment precedent in her dissent. She engaged in no such hypotheticals, nor did she present any neutral principles. Instead, she focused on the content of the speech, calling the Court’s opinion a “profoundly wrong” attack on gay rights. With a vague guiding star of social justice, Justice Sotomayor incorrectly claimed the majority gave permission to refuse service to protected classes, even though both parties had said this was not the case and that the designer had only refused to design certain messages.

Thankfully, these ideological disputes are currently few and far between, and usually only appear in the most divisive cases. Recently, the Court reaffirmed its commitment to strong First Amendment protections in the divisive cases Murthy v. Missouri and Moody v. NetChoice. Murthy dealt with government-pressured censorship, and Moody addressed state intervention in social media content moderation. The Court resolved both cases on non-First Amendment grounds, but discussed the First Amendment issues. In Murthy, the Court indicated its approval of the Vullo holding that the government cannot pressure private entities based on their speech (although it declined to apply the principles in that case on standing grounds). And, in Moody, a six-justice consensus of liberal and conservative justices articulated a strong First Amendment framework for rejecting government interference with social media companies’ content moderation.

Today, in First Amendment cases, the 3-3-3 and 6-3 breakdowns are rare, suggesting the justices generally base their decisions on First Amendment precedent instead of partisan concerns. But certain methods of interpretation threaten this adherence to First Amendment precedent. The Court must continue to impartially assess the government’s power to censor or compel speech regardless of the content of that speech.

If we stray from this task, the First Amendment will hold no weight.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

Walz/Vance VP debate another reminder it’s time to extinguish the ‘fire in a crowded theater’ trope

Seth Berlin: Some further thoughts about K-12 student speech, including the on-campus/off-campus distinction — First Amendment News 442

American writer living in Germany could face jail time for using satirical swastika to voice dissent