Table of Contents

Seth Berlin: Some further thoughts about K-12 student speech, including the on-campus/off-campus distinction — First Amendment News 442

First Amendment News is a weekly blog and newsletter about free expression issues by Ronald K. L. Collins. It is editorially independent from FIRE.

Last month I posted a piece that argued that public school officials too often mistakenly assume they have the power to regulate off-campus speech, absent some specific state legislation authorizing such actions.

The point of that authorization argument was clearly articulated by Larry Levy (the respondent’s father) in the 2020 Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. case: “The school stepped outside of their gates and took action . . . when it would have been my [duty] as a parent to deal with.”

Furthermore, the spirit of that same authorization argument is likewise captured by Judge Cheryl Ann Krause in her thoughtful Third Circuit opinion in Mahanoy:

The heart of the School District’s arguments is that it has a duty to “inculcate the habits and manners of civility” in its students. . . . To be sure, B.L.’s snap was crude, rude, and juvenile, just as we might expect of an adolescent. But the primary responsibility for teaching civility rests with parents and other members of the community. As arms of the state, public schools have an interest in teaching civility by example, persuasion, and encouragement, but they may not leverage the coercive power with which they have been entrusted to do so. Otherwise, we give school administrators the power to quash student expression deemed crude or offensive — which far too easily metastasizes into the power to censor valuable speech and legitimate criticism. [Emphasis added]

In the discerning post below, Seth D. Berlin (a noted media lawyer) elevates the discussion to a related and important level — namely, to the question of the distinction between speech on-campus and off-campus.

In reflecting on Ron Collins’ Sept. 17 First Amendment News post on whether the Supreme Court can empower public schools to regulate off-campus speech (the title emphatically declares, “No!”), I was struck by the complexity of the question posed, especially in light of the decision in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., which features prominently in Ron’s piece.

A thorny question with no clear rules

I take Ron’s point about the difference between what a state authorizes and what the Supreme Court allows as a constitutional matter. But before he gets there, he starts with a series of circumstances that he describes as “off-campus.” With apologies for challenging the setup of the question he answers, the issue of what is “on-campus” and “off-campus” — and the related question of the role that dividing line plays in K-12 speech cases — seems to me, both as a factual and legal matter, to be a thorny one.

Given the facts of the case, involving a cheerleader’s after-hours speech on social media about a school program, the Court was clearly struggling with the boundaries between “on-campus” and “off-campus,” a question made far more difficult in the age of the internet. As a result, Justice Breyer’s opinion for the Court in Mahanoy (with only Justice Thomas in dissent) is pretty clear that it was not adopting categorical rules. “Particularly given the advent of computer-based learning,” the Court explained, “we hesitate to determine precisely which of many school-related off-campus activities” may be regulated. To the contrary, the Court expressly said it would “leave for future cases to decide where, when and how” the general principles it articulated ought to apply, noting that this case provides but one example. While an opinion eschewing categorical rules is no surprise coming from Justice Breyer, it was more surprising that he was joined by eight of the nine members of the Court (with a separate concurrence by Justice Alito, joined by Justice Gorsuch, both of whom also signed onto Justice Breyer’s opinion).

Expansively defining ‘on-campus’ speech

Despite the absence of clear rules for future cases, one reading of the decision is that the student prevailed, she was off-campus, and schools should therefore be extremely hesitant to try to regulate off-campus speech. But that conception is arguably undermined not only by the Court’s cautionary language described above but also by (a) how the Court seemed to broadly define what counts as “on-campus” and (b) its discussion of areas where indisputably off-campus speech can still lawfully be regulated and punished. As to the former, the Court appeared to credit the student and her amici’s expansive definition of what counts as “on campus,” including:

- All times when the school is responsible for the student.

- The school’s immediate surroundings.

- Travel en route to and from school.

- All speech taking place on school laptops or on a school’s website.

- Speech taking place during remote learning.

- Activities taken for school credit.

- Communications to school email accounts or phones.

- Speech either related to, or at least occurring during, extra-curricular activities, such as team sports.

Justice Alito, while railing against the idea that all parental responsibility is somehow transferred to a public school simply by enrolling a student, nevertheless largely reiterated in his concurrence that conception of “on-campus” speech, i.e., speech that can more readily be regulated.

Regulating even ‘off-campus’ speech

In addition to this broad conception of what it means to be “on-campus,” especially in the internet era, the Court also stated that school officials retain at least some degree of latitude to regulate even indisputably off-campus speech, explaining that “[t]he school’s regulatory interests remain significant in some off-campus circumstances." Instead of limiting its discussion to just the off-campus speech before it, the Court enumerated categories in which it would be appropriate to regulate off-campus speech, including:

- Serious or severe bullying or harassment targeting particular individuals.

- Threats aimed at teachers or other students.

- The failure to follow rules concerning lessons, the writing of papers, the use of computers. or participation in other online school activities.

- Breaches of school security devices, including material maintained within school computers.

It is hard to take in the totality of all these supposedly helpful examples in Mahanoy and find a clearly marked line as to what may properly be regulated or the ostensibly significant distinction between on-campus speech and off-campus speech. To my eyes, the decision leaves those questions rather out of focus.

Beyond the blurred conceptual on-campus/off-campus line

That fuzzy line aside, the decision also had quite a bit of good news for student speech — including to explain that grappling with controversial speech plays a vital role in educating our adult citizens of tomorrow. Indeed, particularly given that the speech before the Court did not involve political or deeply ideological speech, the decision is extremely solicitous of the free speech rights of minors in a number of respects.

As an initial matter, by my count, the decision marks essentially the first time since Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), was decided 52 years earlier that the Court ruled in favor of a high school student in a free speech case, following a string of losses in cases like Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986), Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988), and Morse v. Frederick (2007). And both Justice Breyer for the Court and Justice Alito in his concurrence continued to recognize that students enjoy meaningful protection for their speech even while on campus.

Turning to off-campus speech, Justice Breyer laid out three “features” of such speech that diminish a school’s interest in regulating it. First, where a school is not functioning in loco parentis, the regulation of a student’s speech is presumptively the parents’ job, not the school’s. Justice Alito offered a lengthy and forceful explication of this point in his concurrence. Second, and relatedly, if the school were permitted to broadly regulate on-campus speech and off-campus speech, students’ speech would effectively be regulated 24/7. Justice Breyer explained that the lower courts must be “more skeptical” of a school’s efforts to regulate off-campus speech when it leaves the student no room to speak at all, especially where the speech is political or religious. Third, and significantly, the Court explained not only that students have free speech rights, but also that a part of a school’s educational mission is to teach the importance of protecting unpopular expression. With respect to that final factor, Justice Breyer pointedly explained (594 U.S. at 190):

America’s public schools are the nurseries of democracy. Our representative democracy only works if we protect the “marketplace of ideas.” This free exchange facilitates an informed public opinion, which, when transmitted to lawmakers, helps produce laws that reflect the People’s will. That protection must include the protection of unpopular ideas, for popular ideas have less need for protection. Thus, schools have a strong interest in ensuring that future generations understand the workings in practice of the well-known aphorism, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

Justice Alito picked up this same theme in his concurrence. He explained that “schools have the duty to teach students that freedom of speech, including unpopular speech, is essential to our form of self-government.” He went on to confirm that:

…there is a category of speech that is almost always beyond the regulatory authority of a public school, [speech] that addresses matters of public concern, including sensitive subjects like politics, religion, and social relations. Speech on such matters lies at the heart of the First Amendment’s protection.

Moreover, the Court notably rejected several interests proffered by the Mahanoy school system in defending its punishment of the cheerleader’s speech at issue. First, it rejected an interest in punishing the use of vulgar language, including because the school was not operating in loco parentis when the student was at home. Second, the Court rejected the school’s assertion that the student’s off-campus speech resulted in on-campus disruption — namely, that the cheerleading coach, who also taught algebra, had to devote 10 minutes of class time to addressing the kerfuffle. This was a noteworthy holding in light of the Court’s admonition that teaching students how to deal with controversial speech is part of a school’s mission. Third, the Court rejected the school’s interest in preserving school morale. As a practical matter, these holdings rejecting the school’s asserted bases for penalizing student speech should, especially when viewed in combination, provide enhanced protection for student speech.

Some conclusions

In sum, while the on-campus/off-campus distinction is likely to feature prominently in future student speech cases, I think it will often prove analytically hard to apply, as the Court’s ruminations in Mahanoy illustrate. Or put differently, while it is fair to ask whether schools have been granted the authority to regulate off-campus speech (as Ron’s piece does), given the fuzzy boundaries between on-campus and off-campus, I suggest it would be far more useful for lawmakers, courts and litigants to focus on the Court’s pronouncements that (a) afford meaningful protection for student speech even when they are at school, (b) curtail significantly the ability of schools to regulate speech designated as off-campus, and (c) admonish schools to teach students how to engage with controversial speech, rather than punishing or suppressing it in the name of teaching morality.

One final observation about language

Neither Justice Breyer nor Justice Alito were especially bothered by the vulgarity of the student’s speech and her repeated use of word “fuck.” In particular, it is noteworthy that, in reciting the challenged speech, Justice Breyer spelled out the word four times in his opinion for the Court. It has been my unscientific observation that the result in speech cases often follows how the court treats the language at issue. In the 1970s, the court had no problem using the full word, including in cases like Cohen v. California (1971), which involved a jacket bearing the words, “Fuck the Draft,” or in Hess v. Indiana (1973) (per curiam), an incitement case involving the statement, “We’ll take the fucking street later.” But by the time of FCC v. Fox Television Stations (2009), Justice Scalia repeatedly elided the word, referring to the “F-word” or “f****ing.” And just a few terms ago, in Iancu v. Brunetti (2019), Justice Kagan managed to address the trademark “FUCT” without even mentioning the word it evokes.

One hopes that Mahanoy will mark a return to the Court’s comfort with vulgar or offensive language that is often at issue in its speech cases — and that such a practice will translate into more expansive protection for speech for all of us.

Seth Berlin is Senior Counsel in the Washington, D.C., office of Ballard Spahr LLP. He is the author of “Teach Your Children: High School Students and the First Amendment,” in Communications Lawyer among other publications. The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of his firm or its clients.

Related

- Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. (3d Cir. 2020) (Kraus, J.) (“. . . our rule leaves some vulgar, crude, or offensive speech beyond the power of schools to regulate.”)

- Amicus brief in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. (SCOTUS) on behalf of Mary Beth and John Tinker in support of respondents (Robert Corn-Revere, counsel of record) (“The Third Circuit properly read Tinker as a narrow exception that allows only limited speech restrictions.”)

- Comment, Mahanoy Area School District v. B. L., Harvard Law Review (2021) (“If modern judicial interpretations of in loco parentis are applied to student speech, the effects could be similarly devastating. As defined in the eighteenth-century writings of William Blackstone, a school’s in loco parentis authority arises implicitly out of a consensual contract with a parent for a child’s private education. Under this framework, in loco parentis authority derives from and is commensurate with the authority implicitly delegated by the parent to the teacher or school. But modern courts applying in loco parentis have failed to capture this important limitation in its historical meaning and have instead construed it as a source of plenary power for schools. . . . This omission is particularly inappropriate because parents in today’s state-mandated education system enjoy far less choice to decide between schools than did parents schooling their children centuries ago when private, contractual arrangements were the norm.” (footnotes omitted).

Smartmatic and Newsmax settle defamation case

- Randall Chase, “Voting Tech Firm, Conservative Outlet Reach Settlement in Election Defamation Case,” Associated Press (Sept. 27)

A settlement was reached Thursday in a defamation lawsuit brought by electronic voting machine manufacturer Smartmatic against conservative news outlet Newsmax for airing accusations about vote manipulation in the 2020 election made by allies of former President Donald Trump.

The settlement was announced just a few hours after jury selection began in the lawsuit filed by Florida-based Smartmatic against Newsmax.

Smartmatic claimed that Newsmax program hosts and guests made false and defamatory statements in November and December 2020 implying that Smartmatic participated in rigging the results and that its software was used to switch votes.

Newsmax argued that it was simply reporting on newsworthy allegations being made by Trump and his supporters . . . Newsmax has said the lawsuit represented a threat to freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

[. . .]

The terms of the settlement were not disclosed, but Newsmax has said Smartmatic recently dropped its damages claims by more than $1 billion.

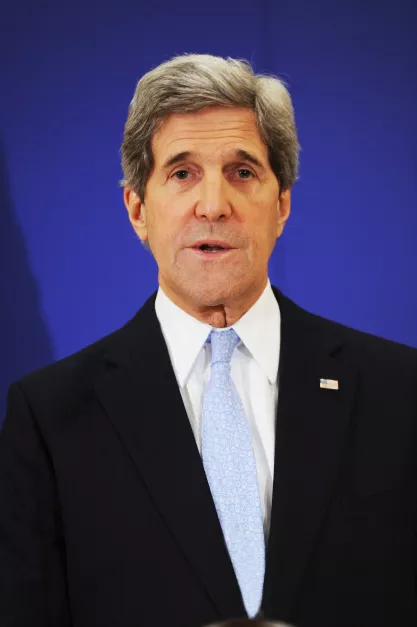

John Kerry: First Amendment is ‘major block’ to weeding out disinformation

- James Lynch, “John Kerry Says the First Amendment Is Getting in the Way of Online Censorship,” National Review (Sept. 29)

Responding to an audience question about “climate misinformation,” Kerry described how social media makes it difficult to form consensus and said the First Amendment makes it difficult to weed out “disinformation” online.

“But, look, if people go to only one source, and the source they go to is sick and has an agenda, and they’re putting out disinformation, our First Amendment stands as a major block to the ability to be able to hammer it out of existence,” Kerry said.

“What we need is to win the ground, win the right to govern by hopefully winning enough votes that you’re free to be able to implement change,” he added, while acknowledging that different people have other visions for change.

Rauch and DiResta on free speech and content moderation

- “Debating social media content moderation,” “So to Speak” podcast (Sept. 26)

Can free speech and content moderation on social media coexist?

Jonathan Rauch and Renee DiResta discuss the complexities of content moderation on social media platforms. They explore how platforms balance free expression with the need to moderate harmful content and the consequences of censorship in a digital world.

Jonathan Rauch is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the author of "The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth" and "Kindly Inquisitors: The New Attacks on Free Thought." Renee DiResta was the technical research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory and contributed to the Election Integrity Partnership report and the Virality Project. Her new book is “Invisible Rulers: The People Who Turn Lies Into Reality.”

Gene Policinski’s new First Amendment book

- Gene Policinski, “From the Village Green to the Village Screen,” Freedom Forum (2024)

The First Amendment, adopted in 1791 with the rest of the Bill of Rights, protects our core individual freedoms from encroachment or abuse by the government.

The five freedoms in the First Amendment — religion, speech, the press, assembly and petition — were seen by the nation’s founders as the natural rights of each human being, not as rights given or granted by those in power. It’s necessary to note that this aspirational declaration fell short from the start because enslaved people, some 700,000 people at that moment, and Native Americans (as tribes made treaties — often coerced — with the U.S.) were excluded from its direct protection.

The nation has struggled ever since to fully correct not only this injustice but also to interpret and apply the amendment’s 45 words to a dynamic, increasingly complex industrial and technological society.

That struggle has moved through three eras:

- Debate and dissent on colonial Village Greens, rooted in freedom of conscience and religious faith, and expressed through free speech and a free press that powered the creation and first century of a revolutionary democratic republic.

- Foundational decisions in courtrooms and Congress in a second century, often driven by public voices powered and

- A dynamic, turbo-charged exchange of information and debate in today’s era of social media communities, our “Village Screens.”

Along the way, the extent, range and questions over the very need for First Amendment protections have been at issue.

The great social media revolution has, in many ways, brought us full circle in terms of public engagement, affording us, via the village screen, quick access to virtual communities that would have been available to our predecessors centuries ago through a simple stroll to a place of public gatherings.

More in the news

- Eugene Volokh, “MSNBC Pundit's Tweet Accusing Lawyer of ‘Coach[ing a Witness] to Lie’ Is a Potentially Defamatory Factual Assertion, Not an Opinion,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Oct. 1)

- Michael McGrady, Jr., “Robbins’ Age Verification Law harms more than the First Amendment,” Alabama Political Reporter (Oct. 1)

- Jennifer Palmer, “State seeks to decertify teacher over 5-year-old Instagram family photo,” Free Speech Center (Oct. 1)

- Chuck Douglas, “Bow Schools violate the First Amendment,” Concord Monitor (Sept. 30)

On Tuesday, Sept. 17, the Bow school system clearly violated the First Amendment when it told a resident he could not come on school property “until further notice.” His offense? Wearing a pink armband with two XXs on it.”

- Alex Riggins, “Judge blocks California city from enforcing 1895 disorderly conduct law, rules it likely violates First Amendment,” The Mercury News (Sept. 30)

- Graham Piro, “In major hit to tenure, Muhlenberg fires pro-Palestinian professor,” FIRE (Sept. 27)

- Susanna Granieri, “South Carolina ACLU’s Legal Director on Alleged ‘Suppression’ of Incarcerated Voices,” First Amendment Watch (Sept. 27)

- FIRE, “VICTORY: Federal appeals court rules tweeting about Cardi B shouldn’t get a graduate student expelled,” (Sept. 17)

2024-2025 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Pending petitions

- 360 Virtual Drone Services LLC v. Ritter

- Coalition Life v. City of Carbondale

- Henderson v. Texas

- Murphy v. Schmitt

- Villarreal v. Alaniz

- No on E, San Franciscans Opposing the Affordable Care Housing Production Act, et al. v. Chiu

Last scheduled FAN

FAN 441: “What’s on deck for the upcoming Court term”

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE or Mr. Collins.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

VICTORY: Court vindicates professor investigated for parodying university’s ‘land acknowledgment’ on syllabus

Can the government ban controversial public holiday displays?

DOJ plan to target ‘domestic terrorists’ risks chilling speech