Table of Contents

Whittier Law Professor Instructs Students on the Dangers of Censorship

A group of law students sent an anonymous letter to one of their professors objecting to the fact that she wore a “Black Lives Matter” T-shirt to class; her response has gone viral.

Inside Higher Ed’s Scott Jaschik verified the authenticity of the correspondence, identifying students at Whittier Law School in California as the authors of the original letter and Professor Patricia Leary as the author of the response. The students were offended by Leary’s T-shirt because they found it disrespectful. Professor Leary was not impressed with either their demand that she stop wearing the shirt or the logic behind it. Her rebuttal shows why one of the primary purposes of a university is to provide a “safe space” for the clash of ideas.

Jaschik characterized the students’ letter this way:

The letter said wearing the shirt was “inappropriate” and “highly offensive.” Further, it said “we do not spend three years of our lives and tens of thousands of dollars to be subjected to indoctrination or personal opinions of our professors,” and urged the professor to avoid “mindless actions” that might distract students at a law school where not everyone is passing the bar.

Leary’s response to the students’ demand that she keep her opinions to herself is curt:

Premise: You are not paying for my opinion.

Critique: You are not paying me to pretend I don’t have one.

Behind Leary’s quip lies an important principle of academic freedom: namely, the idea that professors do have a right to express themselves on a range of issues without fear of retaliation. The students’ nod to Leary’s “sacred right to the freedom of speech” does not undo the fact that they don’t want to have to confront Leary’s views. FIRE has defended numerous professors punished for their extracurricular commentary, including Laura Kipnis, who was investigated by Northwestern University over an article she wrote about Title IX, and John McAdams, who was suspended by Marquette University for statements on his personal blog related to a graduate instructor’s discussion of gay marriage in class. The students are correct that they should not be subjected to indoctrination, but a professor wearing a T-shirt does not force anyone to change his or her beliefs.

Much of Leary’s response addresses the students’ criticism of the Black Lives Matter movement. The merits of the arguments made by either the movement or its critics are not within FIRE’s purview. One point Leary makes, however, highlights something at the heart of censorship: that those who want to silence others often mistakenly equate their own opinions with fact. As Leary wrote, “Your interpretation of something and your reaction to it based on that interpretation are not the same as what something actually means.” (Emphasis in the original.) Robust discourse may not guarantee understanding of or eventual agreement with a different point of view. But the opposite—refusing to engage in such discussion and demanding censorship rather than subjecting one’s assumptions to scrutiny—does ensure that people will remain in an echo chamber, cheating themselves out of a meaningful education.

The students end their letter with the hope that the “new administration” will end the “abysmal failings and shortcomings” exemplified by Leary’s insistence on exposing them to ideas they don’t want to hear. FIRE sincerely hopes that the new administration will continue to allow professors the freedom they need to get students to think about the law, not just memorize the rules of civil procedure.

Leary ends her response with a reminder that the true purpose of a university is to be a marketplace of ideas that is always open for business:

I believe that every moment in life (and certainly in the life of law school) can be an occasion for teaching and learning. Thank you for creating an opportunity for me to put this deeply held belief into practice.

And thank you, Professor Leary, for the timely reminder that the best response to speech one disagrees with is more speech, not calls for censorship.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

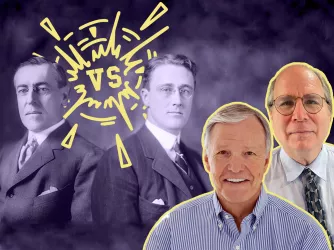

Wilson vs. FDR: Who was worse for free speech?

Podcast

Woodrow Wilson or Franklin D. Roosevelt: which president was worse for free speech? In August, FIRE posted a , arguing that Woodrow Wilson may be America's worst-ever president for free speech. Despite the growing recognition of Wilson's...

Right, left, and in-between: Can we bring our differences to the table?

How to survive Thanksgiving