Table of Contents

Compelling ‘Civility’

Earlier this week, an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education (subscription required) discussed the growing popularity on college campuses of programs aimed at promoting civility. While one might reasonably ask whether there is a connection between exorbitant tuition rates, administrative bloat, and programs such as the "transformational, saturation approach" civility projects discussed in the article, there is no problem from an individual rights standpoint with colleges promoting civility. The individual rights problem, which the article barely even hints at, is that a large number of colleges and universities actually compel civility rather than simply encouraging it.

The article focuses heavily on the Johns Hopkins Civility Project, founded in 1997 by Pier Forni, a literature professor at Hopkins who has since authored two books on civility and has become a popular speaker at colleges and universities. The Hopkins Civility Project is described as "a combination of scholarly and outreach activities aimed at both studying good manners and promoting them, on campus and beyond." That certainly doesn't sound problematic, right? But what the article completely fails to mention is that in 2006, Johns Hopkins imposed severe disciplinary sanctions on a student for posting an offensive Halloween party invitation on Facebook, and immediately thereafter adopted a campuswide policy explicitly requiring people to treat one another with "courtesy and civility" and prohibiting any "rude, disrespectful behavior." The severe consequences of incivility at Johns Hopkins are a far cry from the feel-good, aspirational sound of the Civility Project.

The Chronicle also mentions Harvard University's introduction of a "kindness pledge" to its freshman class last fall. While the article refers to Harvard's efforts as "modest, even token," the kindness pledge actually stirred up quite a bit of controversy. Harvard's student newspaper The Crimson reported that signed copies of the pledge (including blank, unsigned lines next to the names of students who chose not to sign) were being posted in the entryways of Harvard's residence halls, a result former Dean of Harvard College Harry Lewis referred to as "an act of public shaming."

The reality is that many schools go far beyond merely encouraging civility and affirmatively require it. The University of Florida's "Standard of Ethical Conduct" for students, for example, provides that all expressions "need to be civil, manifesting respect and concern for others." Oh really? Does that hold if you find out your roommate is a KKK sympathizer? To what extent are you expected to "respect" him for that?

According to Tulane University's Code of Student Conduct, students "are expected to speak and act with scrupulous respect for the human dignity of others, both within the classroom and outside it, in social and recreational as well as academic activities." Who decides what is dignified and what is not? Is there a book Tulane students can rely on for definitions that encompass guidelines for bringing "dignity" to the whole of human interaction?

The University of Nevada, Las Vegas, prohibits "disrespect for persons" based on a wide variety of personal characteristics, including "political affiliation." I guess sending around YouTube versions of the blizzard of negative presidential campaign ads to your friends is right out, then.

That these and many other universities prohibit incivility stands in stark contrast to a federal court's ruling that San Francisco State University's policy requiring students "to be civil to one another" presumptively violated the First Amendment. The judge wrote that

The First Amendment difficulty with this kind of mandate should be obvious: the requirement "to be civil to one another" ... reasonably can be understood as prohibiting the kind of communication that it is necessary to use to convey the full emotional power with which a speaker embraces her ideas or the intensity and richness of the feelings that attach her to her cause. Similarly, mandating civility could deprive speakers of the tools they most need to connect emotionally with their audience, to move their audience to share their passion.

In sum, there is a substantial risk that the civility requirement will inhibit or deter use of the forms and means of communication that, to many speakers in circumstances of the greatest First Amendment sensitivity, will be the most valued and the most effective.

College Republicans v. Reed, 523 F. Supp. 2d 1005, 1018-19 (N.D. Cal. 2007).

While the Chronicle article provides interesting insight into the mindset of those seeking to foster civility on campus (of particular concern, I think, is Forni's recommendation that college administrators ask instructors to "weave the lessons [on civility] into the curriculum"), it completely ignores the massive free speech problems raised by Johns Hopkins' and so many other schools' civility initiatives.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

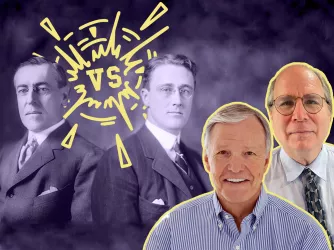

Wilson vs. FDR: Who was worse for free speech?

Podcast

Woodrow Wilson or Franklin D. Roosevelt: which president was worse for free speech? In August, FIRE posted a , arguing that Woodrow Wilson may be America's worst-ever president for free speech. Despite the growing recognition of Wilson's...

Right, left, and in-between: Can we bring our differences to the table?

How to survive Thanksgiving