Table of Contents

Survey data suggests there is a Lake Wobegon effect among campus administrators

Those of a certain age, or at least those who took and retained some information from an undergraduate social psychology course, likely recall the mythical Lake Wobegon: A pristine, small rural town where “all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.”

This famous description of Lake Wobegon captures a phenomenon of which people are widely aware: the Lake Wobegon effect. Social psychologists have many additional names for this phenomenon, such as self-enhancement, illusory superiority, egocentric bias, or the Dunning-Kruger effect. However, the general public may simply call it “tooting one’s horn” or “being oblivious to one’s own weaknesses.” Regardless of what it’s called, the phenomenon appears to be a fairly generalizable feature of human social behavior.

A few weeks ago, I noted that survey data from chief academic officers and student affairs officers reveal that they possess a rosier perception of the campus expression climate compared to what students typically report. A point in favor of treating that conclusion with a heavy dose of skepticism is that it would be shocking to find a majority of college administrators reporting that their own campus is riddled with problems and that they, or their staff, do not think they possess effective solutions. Furthermore, without additional empirical evidence we cannot conclude that college administrators’ perceptions of their own campus are inaccurate.

However, given the volume of ink used to cover issues on campus there surely have to be some campuses that, to a degree, possess some problems. Simply put, if students, faculty, and staff feel like they aren’t free to express themselves without social sanction or punishment, or that their campus has problems with race relations and/or sexual harassment, then that is a problem, regardless of whether administrators think it is or not. Student data from the Higher Education Research Institute and data from students, faculty, and staff on individual campuses suggests that this very scenario is the case.

Below I present some recently collected survey data that demonstrates what can be called a Lake Wobegon effect among college administrators. This analysis of survey data on college administrators (i.e., college and university presidents, chief academic officers, and student affairs officers) finds that they consistently report that race relations, sexual harassment, and tension between free speech and campus inclusion are problems on campuses around the country, but not on their own.

“Race relations on campuses across the country is a problem — but not on my campus.”

Two recent Inside Higher Ed surveys, one of college and university presidents and the other of student affairs officers, revealed:

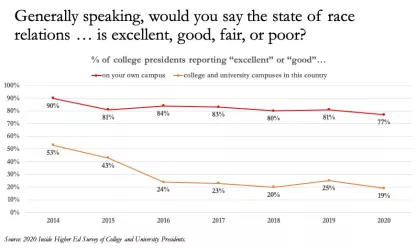

- 77% of college and university presidents rated race relations on their campus as “excellent” or “good,” but only 19% rated race relations on other campuses in the United States as “excellent” or “good.”

- 54% of student affairs officers rated race relations on their campus as “excellent” or “good,” but only 15% rated race relations on other campuses in the United States as “excellent” or “good.”

The large discrepancy between how college and university presidents see race relations on their own campus compared to other campuses around the country has existed since at least 2014:

“Higher education has tolerated sexual harassment for too long. But this doesn’t describe my institution.”

The story is similar for perceptions of how sexual harassment is addressed on one’s own campus compared to campuses around the country. In the aforementioned 2020 Inside Higher Ed survey of student affairs officers, 88% agreed that their institution handles sexual assault allegations appropriately. But 74% of student affairs officers also agreed that higher education institutions must improve the way they respond to allegations of sexual assault on campus.

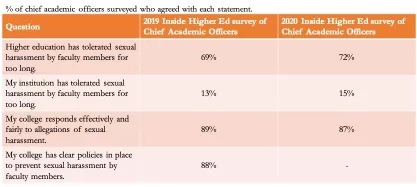

An even clearer demonstration comes from the 2019 and 2020 Inside Higher Ed surveys of chief academic officers. Both surveys asked if “higher education has tolerated sexual harassment by faculty members for too long” and if “[the survey respondent’s] institution has tolerated sexual harassment for way too long.” Officers were also asked about their own schools’ effectiveness at responding to sexual harassment allegations and if clear preventative policies are in place. The table below demonstrates a rather large discrepancy between how chief academic officers think about their campuses in comparison to higher education in general:

Note: All data was obtained from the full survey reports that are available upon request from Inside Higher Ed.

“Free speech and campus inclusion do not work well together. But on my campus they do.”

As noted above, I have documented evidence demonstrating that a notable portion of college administrators have a rosier perception of the climate for campus expression than their students. However, the previous analysis did not include any questions asking for a comparison of the campus expression climate on one’s own campus to the expression climate on other campuses.

A 2018 Inside Higher Ed survey asked chief academic affairs officers about the expression climate on their own campus and on campuses around the country, and 80% of them reported that free speech rights were secure or very secure on their campus. In contrast, only 41% reported the same for college campuses in general. The 2020 survey of student affairs officers, unfortunately, did not ask these questions.

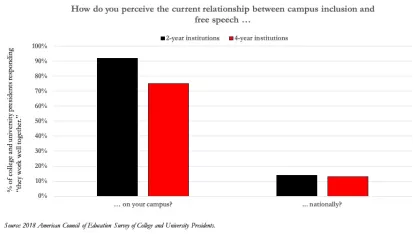

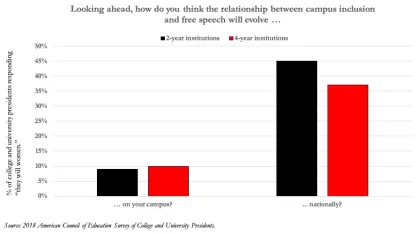

A 2018 American Council on Education survey asked college and university presidents about how they perceived the relationship between campus inclusion and free speech on their campus and nationally. The survey also asked whether they believed the relationship between free speech and campus inclusion would get better or worsen in the future. The figures below demonstrate the discrepancy between how presidents perceive their own campuses and how they perceive others.

The first figure depicts the percentage of presidents responding that free speech and campus inclusion “work well together” on their own campus and nationally. The second figure depicts the percentage of presidents reporting that the relationship between free speech and campus inclusion “will worsen” on their own campus and nationally in the future:

Finally, the 2018 ACE survey asked presidents about how good the students, faculty, and staff/administrators at their college were at seeking out and listening to differing viewpoints. Presidents were also asked about the ability of students, faculty, and staff/administrators at other colleges to do this.

As can be seen below, presidents reported that most of the students, faculty, and staff/administrators at their school were good or very good at seeking out and listening to differing viewpoints. They had less confidence in the ability of students, faculty, and staff/administrators at other colleges.

However, it is interesting to note that the presidents surveyed also demonstrated a general administrator bias. Specifically, the percentage of presidents who rated staff/administrators at other colleges as “good” or “very good” at seeking out and listening to differing viewpoints was roughly equal to the percentage reporting that their own faculty was good or very good at this. It was also slightly higher than the percentage of presidents who reported this about their own students.

Conclusions

In the absence of additional empirical evidence, we cannot conclude that college administrators’ perceptions of their own campuses or of other campuses are inaccurate. However, as noted above, if students and faculty feel like they aren’t free to express themselves without social sanction or punishment, or think that their campus has problems with race relations and/or sexual harassment, then that is a problem regardless of what the administrators think. In the case of free speech, FIRE’s work documenting campus speech codes demonstrates that a significant percentage of schools maintain unconstitutional policies that can be employed to limit expression by students and faculty. In other words, data from a variety of sources calls the rosy perception of most administrators into question.

This rosy perception among administrators may be one reason why many colleges and universities seem unprepared when a crisis on campus bubbles up. If one thinks their campus does not have a problem with a given issue, or a minimal one, then they may not plan adequately for a campus crisis. If they had a more realistic assessment, they may be able to implement better policies and preventative measures in advance. Furthermore, those administrators who do acknowledge that they may have a more positive view of the state of affairs on their own campus compared to other campuses, have an opportunity to be more widely influential. These administrators could choose demonstrate that their campus has sucessfully mitigated problems with race relations, sexual harassment, and/or free speech, and openly and transparently share their methods and the data that support their case.

This kind of openness and transparency may help identify campuses that have successfully deployed solutions to mitigate problems with race relations, sexual harassment, and/or free speech. It would also help those administrators who are willing to acknowledge that such problems exist on their campus deploy solutions that have already proven to be effective at mitigating such problems on similar campuses.

This may be a big ask. Many institutions do not want to empirically evaluate interventions that they deploy in response to problems, let alone publicly share the information they gather. Colleges and universities do not appear to be exceptions to this pattern. Yet, current world events should provide a strong reminder about why openness and transparency on such matters is preferable.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

FIRE’s defense of pollster J. Ann Selzer against Donald Trump’s lawsuit is First Amendment 101

Cosmetologists can’t shoot a gun? FIRE ‘blasts’ tech college for punishing student over target practice video

China’s censorship goes global — from secret police stations to video games