Table of Contents

So to Speak podcast transcript: Free speech, psychology, and madness

Note: This is an unedited rush transcript. Please check any quotations against the audio recording.

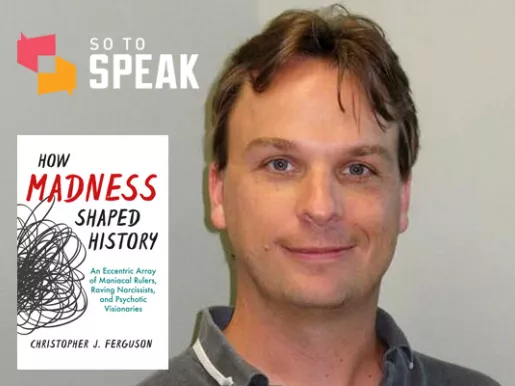

Nico Perrino: Welcome back to So To Speak, the free speech podcast where every other week, we take an uncensored look at the world of free expression, through personal stories and candid conversations. I am as always, your host, Nico Perrino. And today I'm joined by Chris Ferguson. He is a Professor of Psychology at Stetson university in Florida, his research and clinical work explore many issues, including crime violence and antisocial behavior, he's written and researched on the impact of media on viewers, including violent video games. We actually interviewed his co-author of moral combat Patrick Markey over at Villanova, I believe right, Chris?

Chris Ferguson: Mm-hmm.

Nico: Yeah. It seems like forever ago because it was pre-COVID that I interviewed him, but it was really only like the end of 2019. But that was an interesting conversation. I encourage our listeners to go back and check that out. But you've also done research on sex in the media and suicide themed media, and you've authored a number of books, including the aforementioned moral combat, but the most recent one is How Madness Shaped History: An Eccentric Array of Maniacal Rulers, Raving Narcissists and Psychotic Visionaries.

And I apologize. I messed up your cover here a little bit because I read it by the pool yesterday and it started to fray, but it was a fascinating read Chris, because I'm a history major and you usually don't get this sort of perspective on history. I mean, it was a good history book on its own, but you also take a look at the psychology of these people who create a lot of the history that – who wrote a lot of our history. What was the impetus for looking at that?

Chris: Yeah. And I was gonna say, by the way, you have to buy a whole new book now that you've got water on the cover, so.

Nico: You gave me this one for free.

Chris: I don't make them up, that's just how it goes. But yeah, I mean, I love history. Part of the impetus is I just wanted to write a book that was fun for me and that I thought would be fun for other people to read as well, but a lot of it came from – I had read, sort of like the, it was Jared Diamond’s it was like Guns, Germs and Steel and a lot of other books are kind of in that same vein.

The Zeet guy seemed to be over the last few years or maybe a decade or more was this sort of idea that sort of like the main drivers of history were these kinds of like environmental forces so that if the west became prominent beginning during the enlightenment aids, it was an accident of geography, that the correct combination of geographical resources and absence or presence of plagues and things like that, and where war kind of came in and where it didn't. That just happened to be a lucky combination that allowed to sort of European communities to rise and become dominant in the enlightenment era.

And there was a de-emphasis on the, sort of the more traditional sort of like great person hypothesis.

Nico: I was gonna say, yeah.

Chris: The idea that, like without George Washington, that the American revolution would have failed, so the sort of guns, germs and steel argument would be that, like George walked in is largely superfluous to, some other dude would have stepped in and kind of like filled the same role or, a group of dudes or dudettes or whatever would have stepped in and did the same thing. And I think there's something to that. I mean, I really wasn't writing a book to sort of oppose that. I think there are a lot of credible aspects to that viewpoint. But I –

Nico: But I think it’s myopic a little bit, and you point out the case of Winston Churchill, of course, I'm fairly confident that Britain wouldn't have won that war and would have coalesced or fallen into place if it weren't for him. I mean, all the forces save one, Winston Churchill, were arguing for diplomacy and some sort of compromise with Hitler.

Chris: Yeah, absolutely. I had Neville Chamberlain remained Prime Minister following the invasion of Poland, or I think it was an athlete that they were looking at one point, yeah.

Nico: Or hell facts?

Chris: Yeah, exactly. Would the outcome have been the same? Because there was kind of some vibe of, once particularly France failed during world war II that this is kind of looking bad, looking hopeless. And so they benefited from certainly, I mean, of course we can always do counterfactual and what would history have looked like had Winston Churchill not existed, but they certainly benefited from an individual who is able to steal them up and give them morale and give them the grit for lack of a better word to persevere through some of the darkest moments of the battle of Britain in world war II.

So, yeah, I mean, there is this element of either for good or for evil that individuals do matter. And of course, we make that, or at least those of us that are sort of on the left are making that argument right now about COVID 19 and of course we don't know counterfactually what the pandemic would have looked like in the United States in 2020 had Hillary Clinton be president, for instance. There is this sort of suspicion that it would have looked somewhat different. It wouldn't have been great. I think everybody would say that there still would have been pandemic and it would have been bad, but, are there a certain percentage of lives that would have been saved had we had someone different in a leadership role?

I don't know, but that is sort of speaking to this idea that individuals do matter. And the actions of people who are in charge of our societies can have an influence on how things turn out for us, either for good or for bad. It just was more fun for me to write about the bad ones.

Nico: Well, it's hard to imagine that whether you had mow or not, you would get the great leap forward, right? It just doesn't sit that the whole argument and I'm sure like everything, nature versus nurturer, the environment versus the great man theory. It's all a factor, but again, without Mao Zedong, I don't know that you get the 20th-century China that you saw or without Hitler, I'm not sure you get the Germany that you saw or without Steve jobs, I'm not sure you get the iPhone. So, that sort of argument to me is – I have to take it with a grain of salt.

Chris: Yeah, yeah. It is trying. I mean, my hope was kind of to try to bring things back a little bit towards, like you're saying, it's not that the guns germs and steel argument is wrong. It isn't, it's just that it's one piece of the puzzle and that individuals can matter as well. And on occasion, individuals can have outsized dramatic impact on how their societies function or don't function depending on how they themselves are functioning in some situations.

Nico: So, you take a look at a lot of the maniacal and narcissistic rulers in your book. And you taught, you have this quote, you say “human societies have evolved, developed codified laws, accepted that Kings and Queens are not above them and developed bureaucratic checks and balances to prevent power from being centralized on any one mad personality”. So, I wanna ask because it's those sort of checks and balances that have prevented these maniacal rulers from censoring or killing on a whim.

Do those moments come in a unique moment of sanity for society? Like the idea that we put in these checks and balances do they have to come at a unique moment? Is the state of nature of the Hobbsian one where we're all kind of fighting amongst many with each other? I guess, is it unique? Is it to be expected that we get these codified laws or as the madman or mad woman, the state of nature?

Chris: Yeah. I mean, again at the risk of over-simplifying, so yeah, somewhat the sort of default, if you will, is probably the mad person. You know what I mean?

Nico: Yeah.

Chris: So, historically, power has largely been centralized at least during sort of developed, post agricultural revolution societies. So, this idea that – and we can say certainly even modern democracies have power differentials. We're not living in Whoville at this point in time, so I don't want an [inaudible] [00:08:32] there's this utopia that we're now living in. But, there is a tendency for people who drift into powerful positions for one reason or another to try to accumulate power. And so this idea that power should be spread out is really weird in history. It's –

Nico: Why the American revolution was so unique, right?

Chris: Yeah, it was, it absolutely was. And of course, the American revolution itself capitalize on, sort of like political and humanitarian, God, I can't speak today, thought that had been evolving for, really decades or even a century or two beforehand, the humanist movement that it had evolved out of the enlightenment. So, it's not like the founders just off the top of their heads thought of this stuff, they were influenced by other philosophers and stuff. But, there did seem to be that confluence of that sort of philosophy of thought was existent.

It was coming to some prominence and you had a group of leaders who were at least willing to consider it, and again, I don't necessarily want to cast the founders as complete, what would the word for it be, I mean, there's still words –

Nico: Angels.

Chris: Yeah, exactly. I mean, they still had this idea, at least some of them like John Adams of course, were worried about the public and the common person and with possibly some good reason. Over –

Nico: They were public, right? Weren't they, to a certain extent they would have given Washington the kingship if he wanted it. And why not, right? He seemed like a good guy and that's all humanity had known throughout history, right? Was the sort of autocratic rulers and you just hoped you got a benevolent one.

Chris: Right, yeah, exactly. And he had to kind of demonstrate himself as being this sort of benevolent ruler so there was this kind of movement to enthrone kind of a president for life, essentially in the early Republican, it was fortunate that he basically played this role of Cincinnatus, from the Roman Republic of basically turning down power when it was offered to him. So, that was a very fortunate, so there again you have an individual that had walked in and made a different choice and decided to go for some sort of president for life. Which, if I remember, was something that was on the table as an idea for a while there. If he had gone for that or pushed for that, then that might be what we were faced with still today. He would have set that precedent for that.

Nico: Even though we didn't get that, I mean, you still get some of the imagery that might suggest that he were a godlike or king like figure you go into the Capitol dome and you see the apotheosis of Washington and he's sitting on a chair in the heavens lording over all us little people looking up at him. It's hard to think that you would do that for one of your presidents today, like put Donald Trump up in the Capitol dome or Joe Biden up in the Capitol.

Chris: Joe Biden. Yeah.

Nico: Yeah. It's just even silly to entertain that, but they did that.

Chris: Just kind of glad he can tie his own shoes at this point.

Nico: Yeah, glad I can just get the job done. But even some of these people who were informed by the enlightenment had that urge to sensor. I mean, we look at John Adams and the sedition act and although Thomas Jefferson freed those people who were imprisoned under the sedition act, when he became president, he was prone to censorship as well. Have you ever thought about the psychology of censorship? Is the default state of nature to shut up our critics, to shut up our enemies? And what type of person does it take to overcome that?

Chris: Self-aware. I mean, I'm seeing more people now who will kind of come right out and say that they're not free speech advocate. I've had that conversation where I say, "Well, if you really believe in free speech" and they say, "Well, no I don't believe in free speech." Oh, okay. Well at least we’re just half bad. Fair enough. Fair enough. Okay. Yeah. We are in agreement then that you are not arguing in favor of free speech. So, there seems –

Nico: Which is always a weird argument because then it's, what are you in favor of might make right. Whoever holds the level of power, determines what is free and what is not, but usually get a more nuanced argument than that. They'll say, I – but anyway.

Chris: I'm in favor of free speech, but [inaudible] [00:13:08]

Nico: Yes. Yeah. You'll get a go at many free speech advocates called the buttheads.

Chris: Well, I mean, I guess that is that kind of argument that comes out of, I know, the big fight now is over CRT and Delgado kind of had that sense of free speech as being sort of an aspect of oppressive – it benefits the oppressors in society and that sort of stuff. So, I think probably people were kind of coming from some version of that view of unfettered speech benefits the powerful kind of viewpoint, which is kind of the opposite of true but I understand why sometimes people think that.

Nico: Yeah. I mean, there's a whole slew of theorists, including the author of repressive tolerance. Why is his name, I've mentioned his name a million times on this podcast, who argued that you sort of need to sensor in order to create a tolerance within society and that full tolerance is repressive, like tolerating different points of view if they result in differential treatment or perhaps differential treatment can be repressive.

Chris: Yeah. But I think, there is this kind of innate –

Nico: Marcuso. That's who I [inaudible]

Chris: Okay, yeah. I think there is this kind of innate tendency for us – I mean, there was something to this idea of power, so and of course, information and speech and communication is all about power. So, there is a sense of when we're in some sort of debate that yeah, we kind of want to shut the other side up, and it can be frustrating, to come across people and I've felt it, so I understand it. So, that's why I sort of say like, try to resist pat myself on the back and that kind of stuff, but it does take a certain sense of like, Oh, I'm getting frustrated by this other person's argument, but they have the right to make it.

And if I want to convince them or others that my argument is right, I need to come up with some information or factor data. And while at the same time supporting this other person's ability to have a platform, to have an opportunity to speak. And that can be very difficult, I think for a lot of people, and like I said, I mean I have felt the inclination at times were like, oh, wow, that argument –

Nico: Well, it's just easier.

Chris: [Inaudible] [00:15:30] dangerous.

Nico: Yeah, I mean, it's just easier, right? Because you don't have to do the work. And if you have all the weapons behind you, you're one of these eccentric or maniacal rulers that you write about in your book. It's fairly easy to do, but there's a question as to whether it's effective. Is it actually effective affecting the sort of result that you want to shut people up? Do the ideas disappear? I think it's hard to kind of know exactly how effective that is because if the censorship works and the ideas do disappear, we probably wouldn't know about them.

Chris: Right, yeah.

Nico: This sort of censorship would probably need to be all encompassing in order to not let them leak out. I think you'd probably get some of that North Korea or maybe a little bit during the role of Mao Zedong, but tactically. I mean, at least in modern times, it ends up making martyrs out of those you're trying to censor. And of course, if your goal is truth discovery, then you'll lose a lot by shutting people up.

Nico: Right. Yeah. Well, there again, I think that for a lot of people, the goal isn't truth discovery. I think that we construct worldviews, right. We have these sorts of narratives about how the world works, whether they're religious or political or anything else. And our inclination is to be hostile towards anything and in psychology we have the idea of confirmation bias or my side bias, which are kind of related ideas. The gist of it is that when we have a piece of information that supports our worldview, we tend to soft pedal it. We tend to not question it for the most part.

And when we come across a piece of information that conflicts with our worldview, we usually aren't very curious about it. The ideal of course is to be curious, is to say, well, I used to think this thing was true. But I'm sort of curious to find out if it's not, and particularly if it's something we're emotionally invested in, there is this also this element of like emotional and moral investment of things that makes things harder for emotionally and morally invested in particular worldview, or we have our reputation, like it's the Ferguson theory of everything. And that a piece of data comes by and says that, if I've got a book that says something is true and somebody else comes out with information that says, my book is wrong.

Well, I still want people to buy my book. So, I can't like, just like back down and say, ah. I mean, the ideal is that I would, right? The ideal is I say, "Hey, I thought this was true. People should stop buy my book." And I think there's one or two examples of authors who have actually done that but they are very, very rare. The human inclination is actually to sort of dig in one's feet and say like, there must be something wrong with the source. I just had a little Facebook debate today. It wasn't acrimonious or anything, but it was over the protests in Cuba. And this one person was saying that this was all like a CIA plot to like instigate these protests.

And somehow it was going to result in like the U S was going to invade Venezuela. I don't know how they got from Cuba to Venezuela, but nonetheless.

Nico: Probably by boat and then by land.

Chris: I’m not sure how that – But I kind of, yeah, I don't know. I honestly don't know anything about the politics of Cuba or more than the average person, I suppose. But I sort of went and looked at – I found a survey, it was done, I think by the University of Chicago and they actually managed to survey Cubans. And the data was, I said like 54% of Cubans would move out of Cuba if they had the opportunity to do so. And most of them would move to the U S and I said, well, what do you think about this? And the reply was like, well, that comes from the University of Chicago, which is like this imperialist, CIA funded, I mean, I'm exaggerating a little bit, but they did say –

Nico: No, I know. I get the gist of what they're probably trying to get at. Yeah. I could probably imagine how that conversation went from there, but this idea of confirmation bias and it's sort of very, I'm assuming very recognized concept within the field of psychology. Does the field of psychology do a good job of moderating that within itself? Like –

Chris: No.

Nico: Because I think about Jonathan Haidt, right and social psychology and the sort of work that he does and I remember he told this story and he went to some sort of conference and he asked people to raise their hands if they were conservative, pretty much anything other than liberal and no one raised their hands, and that doesn't mean that they don't exist. It's might just mean that they're fearful to raise their hands in an environment where everyone is elsewhere. But if you think in a field like psychology which is your field, you would understand these innate biases and then would create some sort of institutional disconfirmation to fight against them. But it sounds like 'it' is very strong within psychology.

Chris: Very 'it' driven field. Yeah [inaudible] [00:20:40] true that – I mean, so I'm on the left. I'm a pretty liberal person. I've voted for Biden and Obama, and I don't think I've ever voted for a Republican for any major office. But most people in academia and certainly including psychology and then now feels like they're at the left of me. I'm probably the closest as a sort of Clinton –

Nico: Well you're a neo-liberal there Chris.

Chris: I'm voting, yeah, I'm the conservative now on campus. So, but no, I mean, and it comes right from the top and we have an organization, the American Psychological Association that I was on the council of representatives for three years. So, I got to seat out some of it functions on the inside and it's not a science organization. It's a Guild which is fine because –

Nico: There's room for that. People like myself, we pay money every year. I'm a member and it's supposed to represent our profession, but it's not a science organization. So, watching these things – so first off, as council members, we were typically asked to vote on things. We had no idea what – we had no personal information about whether this thing was true or not. But a lot of them were politically loaded, sorts of issues. So, it tends to function –

I mean, first off it is a marketing firm for psychology is what it is, but it also tends to function because most of the members are pretty far on the left, certainly much further on the left than the average person in the general public. It tends to function as kind of a quasi, progressive organization which again, isn't necessarily a bad thing except that it supposed to be science, right. And if it is only taking left or far left views on issues and does so quite often, I used to make the joke that President Trump couldn't fart without the APA releasing a statement opposing it. And so if it’s that kind of –

Nico: And has APA always been like – you've seen, especially in the last four years, five years, the politicization of a lot of these apolitical organizations issuing statements on things that you 10 years ago would have never issued a statement on because it was outside the mission. I imagine you've been a member or at least watched it –

Chris: Long, yeah.

Nico: For a long time. Have you seen that trend towards politicization in recent memory, and this maybe gets into a little bit of the polarization discussion that you have in your book too.

Chris: It’s gotten more so I would say, I think it's always been somewhat of an issue for the API, at least going back several decades I would say so I mean –

Nico: You see it with like the MLA and the modern language association too, and a lot of these other associations. I mean, it's their right to do it. It's just a question of whether it corrupts science.

Chris: Yeah, yeah. Whether it was a good idea, and I guess short term, maybe it is, but long-term, it's a bit more questionable, but yeah. I mean, of course the APA’s had long issues with policy statements, like on the violence and video games that I did that has not been accurate for quite some time. But in the sense of sort of like everything politicians do, suddenly the APA has a talk about it. Yeah. I think the frequency seems to have gone up and I think part of it for the APA is in 2015, they kind of – I'm gonna tell a short version of the story, but eventually they got caught if you will changing their ethics laws to allow psychologists to be involved in the torture of detainees in Guantanamo bay.

So, that was a massive humiliation for the APA. They basically sort of collaborated with the Bush administration and eventually the Obama administration to sort of allow some of the stuff to happen. And I mean, of course, for an organization that's supposed to be ethical and sets the ethical guidelines for our field to then be sort of caught out doing some of this stuff was pretty bad. So, I think as a consequence, we also have this idea that comes out of Floridians, like analysis reaction formation, which is when you start doing the exact opposite thing of what you're naughty. So, in other words, you cheat on your wife, you come home and you bring her a bunch of flowers and a new Volkswagen – Volkswagen? Terrible. BMW

Nico: I don’t think that’s gonna help.

Chris: I was like –

Nico: A Volkswagen's the poor man’s BMW.

Chris: I was definitely incorrect. BMW, yeah. You only feel a little guilty if it's a Volkswagen. To some degree, I think the APA is trying to show how just with a capital J the organization is even though they really haven't changed much, that sort of the internal workings, my impression of the internal workings of the APA is that they're still a very bureaucratic fiefdom that is still basically a marketing firm and runs like a marketing firm for psychology and even that might be a little generous.

Nico: But is there any recognition that there is a danger in the lack of diversity that exists at least ideological diversity that exists within the field or within all fields. I mean, we have this general concern in America and the world right now for science. All the science and all the studies seem to indicate that a lack of ideological diversity produces extremes on any end of the spectrum, depending on where the echo chamber exists. But there seems to be very little interest in doing anything about it. And science would suffer as a result.

Chris: I fully agree. No and I think, of course, working in academia particularly, the last four or five years have been eye opening to some extent so before my current institution, I worked at a state school in Texas on the border of Mexico, in fact, in Laredo, Texas. And so I was kind of familiar with some of the politics around this Republican administration in Texas, the state legislature was highly Republican and pretty hostile to academia. And at that point, we all were liberals. There are a few conservatives, but they were sprinkling among a few of the liberals, but for the most part, it felt – I think that it felt like the conservative legislature was exaggerating the degree to which we were indoctrinating kids.

I was always [inaudible] [00:27:10] the language that we were indoctrinating kids. That was probably like 2005 to 2013 that I was working there. Now, I kind of agree that at least what's happening to some degree. I'm not saying that the conservatives aren't exaggerating it at all, but now I would have a difficult time disagreeing with the idea that at least some indoctrination is occurring at universities and that some students are being pressured into taking positions that they may not think are true, or they're not being presented with all the evidence both for and against a particular viewpoint and such.

So, and yeah, I would say to raise that as an issue invites itself a fair amount of pushback and that's okay. Pushback is okay. But there is this kind of fear, particularly in the last year that could result in a job loss or, some other official sanctions or something of that sort for speaking, on the record or getting caught speaking off the record about, some of these issues. So, I think there is a palpable fear in academia, not to say K through 12, also possibly about deviating from this orthodox [inaudible] from an orthodox position, or even speaking about the idea of diversity and education, most people don't care about it.

And I think there even have been these surveys that have come out that have suggested that particularly younger scholars are much more okay, actively discriminating against a job applicant who was, for instance, more conservative. And that's not good.

Nico: No, no. I mean, you try and create these guard rails within institutions when you notice phenomena like that, right. In order to check them you have this in grading procedures, you do blind grading. You don't know whose paper you're grading, for example. You would think, after a while, after you see all the research Cass Sunstein and others research on the importance of ideological diversity, you avoid extremism, which is a worldwide problem and phenomena at this point that the scientists would come up with some sort of solution and there would be some sort of care to implement it.

But I, only see it getting worse, right. The question of indoctrination which you bring up is an interesting one and is obviously hot button right now because you see it with a lot of the critical race theory discussions which are fraught and have so much nuance that's being avoided that it's hard to even scratch the surface of it. But we're dealing with a situation right now at University of Oklahoma, where they have these writing instructors who are training faculty, these are mandatory trainings. You don't have to attend this particular training, but this is one of nine trainings. And if you're a graduate student, you have to attend two of them.

If you're a adjunct faculty, you have to attend one. And they were essentially teaching faculty members how to guide their students towards the right perspective. There's this one quote from this instructor who says, this is how you respond to a student who might be entertaining the idea of listening to a problematic argument. And then they even go so far as to say, if the student is still wanting to write about the pronoun debate, for example or is expressing using any white supremacist sources or expressing any white supremacists ideas, which it's hard to know what they mean about that, but in some quarters, that could mean supporting the police, it could mean, X, Y, or Z conservative position, then you report them for a student code of conduct violation.

Yeah. And that's literally what she said. One of the faculty members said, no I just try and have a conversation with them about it. And the other faculty member, given the training said I'm not so kind. Essentially, I tell them they can't explore those topics and if they continue to do it, then I report them for a student code of conduct violation.

Chris: Wow.

Nico: We put up the fall right up on it and we got a statement from the AUP at Oklahoma condemning us for it and they said the classes that they're training these instructors for are meant to quote "explore multiple sides of an issue" or quote "explore an issue from multiple sides, whether their initial position is progressive or conservative" which I like to be charitable, but that's gaslighting to the 10th degree. I mean, that's not what that training was. The training was to push people to a progressive mindset and progressive topics and label anything that wasn't essentially white supremacy. And you kind of talk about that a little bit in your book as a tactic in today's polarized debates is nobody's listening to each other.

Because on the left, they'll call you a racist or sexist or white supremacist. On the right you have, you're calling everything critical race theory and banning it and –

Chris: [inaudible] [00:32:28]

Nico: Manipulating curricula. Yeah. To a certain extent, a lot of this is happening in K through 12, right? That's where a lot of the concerns of in K through 12 education, unfortunately for better or worse and maybe necessarily isn't enterprise, almost an indoctrination. I remember growing up and having to take a constitution class and we were taught all about patriotism and – but at least in the higher Ed environment, that's not what the purpose is. I mean, it's about the creation, dissemination and preservation of knowledge, all of which kind of indoctrination is the antithesis of.

Chris: Yeah. Well, I mean, I guess if you're teaching like values. I mean, there is a sort of sense of education has always been partially about teaching values as well as facts, but it's kind of the sense of if you're kind of teaching civics if you will like free speech is important or due process is important. That's different if you're sort of like obfuscating actual facts. So, I think that there's like the classic book, like lies my teacher told me, right. The sort of sense of sometimes teachers would teach you something about – what this brings to mind is like Helen Keller, right.

Who is this icon of pushing for the rights for people with blindness and deafness, physical disabilities.

Nico: Yeah. Disabilities, yeah.

Chris: And she also was like a raging socialist, and usually people leave out the raging socialist part and just put – some people say communist. I don't know if it's fair to call her a communist or not. I'm not super familiar with their biography, but –

Nico: That's a whole other discussion. Can we separate the different components of an individual? I mean, Henry Ford was a raging anti-Semite, but he also created the –

Chris: And a capital R not like by the modern up[inaudible] [00:34:25]. I go like just out there, segregationist. So, but on the other hand, these usually ranked as a pretty, a successful high-ranking President. But there's, I mean, there's no question in his case that he was an avowed racist and such and again, so we should –

Nico: And also a subject in your book, right. You're talking about Wilson here.

Chris: Yeah. He's an interesting fellow. He hit on a really interesting point in history. And he is this sort of interesting, like counterfactual, like what if he didn't have high blood pressure, would he have had those strokes? And would the world look different if only he had maintained his functioning in the last years of his presidency. But I think we can be honest with – I mean I think that's the trick is, to argue here's kind of what happened and history is messy and crappy things happen and here's kind of like the larger context of why things happen.

But I think what we have with history, particularly in K through 12 and university as again, these competing worldviews is and the conservatives want to tell the utopian story of American history. Whereas, for some reason, the left have just completely jumped off into this dystopian version of American history without any redemption. It's kind of the Howard Zinn school of history. That was an issue. I don't know if you've ever read Howard Zinn's –

Nico: The People’s History of the United States.

Chris: Yeah. It was –

Nico: I haven't read the whole thing though.

Chris: [Inaudible] [00:35:52] there was a clear decision and the United States chose exactly the wrong decision at every turn. It was like, I don't know, 400 pages of that. And so yeah, So, I mean, I think there is this kind of fight where both sides, I mean, I'm both side [inaudible] are kind of trying to obfuscate pieces of factor information that are not supportive of their worldview and they want to kind of enforce it. They kind of want their version to be the one that gets taught to kids.

Nico: Yeah but there is a environment and this is kind of the enlightenment environment that I'm in favor of. You talk about values in higher education. The values that we advocated for at fire are very much enlightenment values. You could have and Jonathan Haidt talks about this, you could have an environment – that you could have a social justice university as Haidt puts it if you want. You just gotta be open and honest about it. We're kind of advocates for the enlightenment model which is the discovery, creation and preservation of knowledge.

And in any environment like that, there are certain values which do a better job of pursuing that mission than other values. Thought reform, indoctrination, censorship, aren't great knowledge generating values in the same way the other ones are but –

Chris: Well, and you can see, I mean, the interesting thing for me over the last again, decade or so, and I think it started on the right more in fairness. And I think the left sort of follow along with that is even debates about these values and because you can see these arguments about like take free speech, which I think I would agree with you is sort of a fundamental value that is best for everybody. And you'll see both on the left and right arguments say that's not true.

And that in fact, we need to restrict people's access to speech and it's for their own good. It always comes into the sense of, it's not for the powerful, we're trying to protect the children or the disadvantage or whatever else or even due process –

Nico: You talk about that a little bit in your book too.

Chris: The sense of like, well – and again, you see it on both sides. There's a sense of well, if someone didn't commit the crime, why were they arrested? Well, that's not evidence. That's not how you decide if someone's guilty of a crime.

Nico: But that's the psychology that you find throughout human history, right? As a rush to judgment, you find that the people, when they're so certain that someone is guilty, they don't want to put in the processes to ensure the just outcome. If you go into the Department of Justice today and everyone has different opinions about the department of justice but above their library and I'll never forget it, they have this beautiful mural of a judge with the book of laws, holding out his hand as a mob in skeleton start racing up the courthouse steps. And there's this man who's crawling up the steps clearly who was being chased by the mob.

Again, this gets back to the first quote that I put out there is we codify these bureaucratic processes to fight against our psychological instincts and our psychological instincts are not friendly to free speech, they're not friendly to deep due process, they're not friendly to really the rights of any man or woman, right? And that's why I think the last 300 years of human history is so special because it's been able to recognize through enlightenment values and an enlightenment inquisitiveness that these – life is better if you put checks on human instinct but this might be the forever fight that'll never be one because you're fighting against human nature.

And you talk about tribalism in your book and the innate instinct we have to separate into our tribes. You talk about one of the great studies and maybe if you could wax poetic on this is that one about the school, not the school children, the camping children, the killed children. At the camps.

Chris: The robbers cave, I think.

Nico: Yeah.

Chris: Basically with that again sort of short version of it’s that they took

some kids and I don't remember exactly how old they were but they were, sort of 10, 11, somewhere in that range. I believe they were all boys and just randomly assign them into two separate camps, I think they were like the Eagles and I forget what the other one was called the coyotes or something like that, basically gave them animal names.

And they had no contact with each other whatsoever, at least initially they just were in two separate camps for a while and then they started to bring them into competitive contact with each other, so remember they were randomly assigned, they knew that they were randomly assigned as far as that can be internalized into a boy's head at least but they knew that they weren't like picked because they were smarter or braver or stronger or anything of that sort.

But then they started to bring these two camps into contact with each other competitively, so in other words they would compete a tug of war and whoever, whichever side won would get some sort of small prize or something of that sort and very quickly we end up with people start to or the boys start to think like, well the coyotes, they're all idiots, they're all woosies, they're all bad, they're all evil, so you see how prejudice develops as a context of this sort of intergroup conflict.

And then what they do at the very end of it is they eventually then bring the two groups together cooperatively and I think it was something like, there was a truck that was broken down and the truck had food that they both needed for their camps and so they had to work together to effectively push the truck to get it to where they could actually benefit from the food. I may be mangling some of the details but that was kind of what happened and at that point, once you see that the two camps worked cooperatively with each other than that prejudice kind of diminished, went away, they had more positive views of the boys on the other side, they kind of like, “oh, you guys aren't so bad after all” –

Nico: Is that a solution then to our polarization? When you actually talk about this, you talk about how, like, external threats that can have a way of pulling people together, you look at 9/11 and all the American flags that were hung around but you'd think that COVID-19 might've been that moment but it's only supercharged the tribal instincts and the polarization.

Chris: Yeah. It suggests that there are certainly some complexities. I mean, if you kind of think of like diversity training, I mean the evidence we have in diversity training which is kind of complicated but basically suggest that the stuff that works best tends to be the stuff that brings people together cooperatively, develops the idea of like separating people into like different affinity groups and then using the more divisive language that the white fragility kind of programs of Robin DiAngelo don't seem to work, if anything, they seem to actually backfire, which we would expect given these kinds of results in the robbers cave experiment but it does suggest that there are some obvious nuances and stuff around things like, yeah COVID-19 didn't work. I remember 9/11.

It was the opposite because 9/11 it was, if anything, if need to use the buzzword problematic, it was problematic that there was so much group thing around because that led to some serious errors, that there was no questioning of the government or very little, very few people were, there was this sort of sense of like you can't, you're not patriotic if you question the war in Iraq, you're somehow not supporting the troops and so there was a lot of like group thing and pressure to conform around that. It did create a result in this cohesive national identity.

And if you look at things like race relations, back in the 2000s, they were pretty good that both black and white Americans, the majority of black and white Americans 60, 70%, 75% were largely satisfied with how race relations were progressing at that time. And events like World War II are kind of similar to that but you could see people now coalesce in all the debate kind of goes away even world war 1 to a somewhat lesser extent. Yeah but maybe it needs to be other humans, I don't know, I mean, I'm just speculating this point, we don't have good data on this but maybe the missing element is that we didn't have a bad guy with COVID-19 nobody's at fault –

Nico: Well if you're on the road, you have Fouche. If you're on the left, you have Trump.

Chris: Yeah. I mean for me 2020 was really for me, this sort of eye opening experience and just how irrational people really are and I mean smart people, people with PhDs, that's like us, the kind of people that are in my social circle for better or for worse, you can say I have a limited social circle, that’s probably true, but there are smart people, at least they have doctor, a lot of them have doctorates or most of them are at least college educated for sure and their responses were irrational, completely irrational –

Nico: Well if you say, that's another interesting topic and social psychology is like how we've sorted ourselves. You don't have as much intermingling between different age groups as you used to, we're sorting ourselves along education levels and various others, Charles Murray wrote a book coming, you can't cite Charles Murray anymore but he wrote Coming Apart, about the various... So, that can probably develop the same sort of extremism that we've been talking about for this conversation as well, where we choose to live and who we choose to hang out with.

Chris: Yeah. It’s very complicated, I mean, obviously there's going along with that, there's a lot of breakdown of just civic organizations, the idea that people from who were Republicans and Democrats would all get together at the bowling alley or something like that –

Nico: Yeah, the Robert Putnam idea.

Chris: Yeah. It's all gone, that's all gone, for the most part, it's sort of interesting. I live in a neighborhood that's actually probably unusually diverse in almost every way you can think of it both racially and politically diverse and so we have a Facebook page –

Nico: Oh we got one in our community too, yeah.

Chris: But actually we, I think our neighborhood kind of handled it because we had people that had like the Trump signs up, we had people had the Biden's signs up and this kind of stuff and we actually managed to navigate that for the most part. I think we kind of came up with the rules that you can have the signs up, but you can't put anything, any more divisive so obviously there's some censorship for like the better social good sort of element, but it's something we all kind of agreed on, so it's sort of like he can have a Trump sign up, a Biden sign up but you can't have either like a black lives matter sign or like the blue line kind of like that's the stuff that'll piss people off and –

Nico: Are you in a homeowner's association or is it like a voluntary?

Chris: Yeah, It’s an HOA, but this stuff was mostly voluntary, I think there probably are some HOA rules about what you can post as well –

Nico: Yeah, I used to be the president of a homeowners. My old one did the worst job I've ever had, but –

Chris: It is, yeah, I can imagine.

Nico: Yeah, you can never make it, you can never make anyone happy, but we had it written into our bylaws, which makes enforcement easier because anytime you can avoid any sort of allegation of arbitrary enforcement, the better, also for the broader community that I lived in had a Facebook group as well. I moved recently, I moved earlier this year, that community had like a 1000 person Facebook group. And the one I'm in now is like a 100 person.

And it's very interesting to see how people behave on social media as the size of the group expands and you expand it even further. I mean, even just look at like Twitter as a whole people behave at least in my experience, much more poorly, the larger the group is rather than the smaller the group is which I guess might be predictable but you think that what you say is on display for a larger group of people, you might behave yourself better but that's not what I found.

Chris: I agree. I agree. Going back 10, 15 years ago when social media was really just kind of starting and we were kind of talking about it, there was this sort of sense of the anonymity being to the advantage of the asshole right so essentially, like people who were anonymous would behave badly and so anonymity was protecting people from consequences. Now a lot of that has flipped. If you look at, I mean that still happens, don't get me wrong but if you look at a lot of bad behavior, it's by non-anonymous people so people are being assholes still with blue checks next to their name and stuff like that.

So, what's interesting about that is now there seems to be social incentives, social credibility, that's built around being behaving badly, as long as that is sort of appealing to you again, your tribe or your tribalism so if you say something ridiculously toxic but you can say stuff that's sexist for instance, as long as you direct it at J K Rowling or Gina Carano or things like that, if you're on the left, you can kind of get away with it –

Nico: Yeah, you’re talking about the Sarah Jeong case.

Chris: Yeah, so there's kind of like these different standards that apply to some of the settings. If you're on the right, you can say something that's, I don't know, horrible as long as you directed at, like Liz Cheney, I guess now you can say whatever you want about her, she's kind of fallen out of favor on the right, even though she's Republican, but yeah. So, as long as the target is the right target, it's kind of like the cliche of punch a Nazi, right. That assault is bad unless it's like a bad person, then you can assault them then it's okay.

Nico: What do you make of social media in general, I talked with your co-author on moral combat and he kind of waved away the concerns that my boss, Greg Lukianoff put in coddling along with Jonathan Haidt about how social media might be making young people miserable, isn't good for the national discourse. And it's kind of in line with the thinking that you all have on video games that they're not having that sort of effect on the culture psyche and the way that a lot of people say they are. Do you continue that line of thinking into social media or do you think social media is more or less detrimental?

Chris: Yeah, I think there are some areas where I probably would agree with Jonathan Haidt and Greg Luianoff? –

Nico: Yeah. Lukianoff.

Chris: And there are probably some areas where I would agree in some where I would disagree in. The main area where I would disagree with them, I think is and I say this respectfully –

Nico: Oh of course. That's what we're here for, disagreement.

Chris: Yeah, but I think there's a lot of this idea of suicides among teenagers are sort of tied to social media and I think at this point we just don't see that evidence that can be supported by the science. First off, the rise in suicides among teenagers is not the most dramatic rise that we've seen in the United States. That's among middle-aged adults actually –

Nico: But you have seen a rise among teenagers as well right?

Chris: Well almost all age groups we've seen a rise in suicide in the last few years, other than elderly people as the only group where we have not seen a rise in suicide but the largest raw numbers and the largest increase was actually seen for middle-aged adults not as a teenager. So, there seems to be something in my opinion, wider that is happening in society that would explain the suicide rise. We also don't really see it cross nationally. Other countries have store high tech adopting but don't have the same trends in the suicide that we're having United States was kind of difficult –

Nico: That’s it, yeah, that's interesting –

Chris: Yeah.

Nico: The most compelling argument that they have for their coddling thesis, is that the sort of bad behavior that social media encourages the sort of like reputational cat fighting that you get hits women harder than men and you see a greater rise in suicides among women than men, or attempted suicides, I think men actually effectuate more of them –

Chris: Yes they do, when they’re actual suicides.

Nico: But if your thesis is that social media is a contributor to this social media, just the way women relate to each other, it would seem to have a greater impact on them than it would on men –

Chris: Right. Yeah.

Nico: But that doesn't mean that there's, definitely cause a relationship. It just.

Chris: Yeah. Well, I think, what we're seeing is that probably the reason that that argument came up is that, with teenagers at least we are seeing that there has been more of a percentage increase in suicides among teenage girls than boys. Now there's also probably a certain amount of what we call like a regression to the mean effect and that the overall numbers of suicides were lower anyway, but they had more reason, more direction to go in than for boys.

But that's probably why, I mean, it feels like a little bit of an ad hoc fit, for somebody say, if it had been the opposite, like if boys suicide rates were increasing faster than girls are probably a good reason to, we could've come up with, well boys actually behave more aggressively on social media and therefore, are on the receiving end of more of that sort of bullying or, you could always come up with a reason why the data are consistent, but somehow still consistent with our, our theory.

The thing that I would like to, I try to get Jonathan on the record with this one is saying, would you agree if we're using suicide rates going up now to support the idea that social media is responsible for that? Would you therefore agree that if social media rates remained high in the future, but suicide rates declined that this would also be evidence against your theory and if they were to say yes, then I would give them a pass, I think. But what we tend to find is that I'm not trying to be like super critical or anything here, but we saw some of the same stuff with video games that when the data are going in the right direction, people tend to look at that data and then once the data tends to diverge, then the data don't matter anymore. So, that's what I would like to avoid more than anything is that, sort of.

Nico: So, if we're trying to address suicide amongst teenagers or any other age group, it's helpful to determine the causal relationship or relationships, right, so in your mind, what does the science say is contributing into it now or do you think it's multiple things?

Chris: It's probably multiple things. Yeah. I mean, I don't think you’d find too many people that would say like one thing is causing so and I'm pretty sure that's not. –

Nico: No, that’s not their [inaudible] [00:55:16]

Chris: So, I don't think anybody's making that particular argument. The question is, is this thing one of the things that is leading to suicide. So, we know that obviously like family environment being around people who have committed suicide or tried to commit suicide, things like that certain types of mental illnesses like depression, of course, and also psychosis, can increase suicide risk, things like shame and humiliation or a fact of bullying is certainly a factor –

Nico: And I think that's what it really comes down to for them is the fact that, if you were getting bullied at school, when you went home, you at least had a reprieve. Now you have a social media environment that can bring the bullying home with you, so you get no reprieve, you maybe get a rise in mental illness, in self harm and suicide as a result. I don't know, this is.

Chris: Yeah, no, I think that's a fair argument. The question becomes is empirically supported. The good news is that bullying in general has been decreasing over the last, at least the last decade or so, all forms of bullying, whether it's in person or online kids in general reporting being bullied less than they were in the early two thousands or late 1990s, so there's kind of been a positive trend in overall exposure to bullying, even with the addition of cyberbullying on top of your regular, a garden variety goal.

So, the trend lines and bullying again, seem to be going in the opposite direction than the suicide thing. My concern is that we're kind of looking at the elephant, right? And we're all just kind of hanging onto the trunk and trying to describe what that thing is, and that we need to look at the trends in and teen suicide in combination with the tech trends in middle-aged adult suicide and everybody else's, suicide. Because one of the things that we do know is one of the big risk factors for suicide, if you are a teenager, is if a parent committed suicide, so if you have middle-aged adults who are stressed and I'm about like in two weeks to hit 50.

So, I sort of sympathize with the place –

Nico: Happy birthday.

Chris: Thank you. Yeah, thank you. I appreciate it. But I mean, I get it, it

is in many ways a stressful period of time and don't get me wrong. I'm pretty happy, dude. Things are going okay for me, for the most part, I don't want everybody to be like, oh, Dr. Ferguson said he's gonna, yeah, no but it is a weird time of life that there is a lot of pressure, a lot of stress and so it's not surprising that we would see middle-aged adults I think having more issues, particularly if you are the cushy academic who has summers off, it's different than if you're the coal miner who just lost his job. Right.

And it has to support a family and stuff. So, I think what we need to look at are how the sort of larger family dynamic is affecting teenagers because I don't think we can separate teenagers off from these middle-aged adults and say well, something is happening to teenagers, which may be a social media and middle-aged adults are also not doing well even though they're less tech adopting and I'm actually doing worse.

But maybe something different is going on there, I mean, I think there's probably some interaction between those two cohorts of individuals given that one is the parent of the other. And that would be more interesting to look at, I mean, exactly what that thing is or what those things plural may be, I'm not so sure, necessarily other than if you just look around in American society nobody's happy, at least it seems that way, sometimes, so I think there's something larger there –

Nico: If you look at social media. It seems that way.

Chris: Well, I don't know –

Nico: Let's say look at Instagram that everything's great.

Chris: That's all cat videos. Yeah. And people dancing.

Nico: Or hanging out at the beach with there ...

Chris: What I did wanna say is I don't entirely disagree with Greg and

Jonathan Dale. On the other hand, I do think there are some risks that come along with social media. I just don't see the evidence for that particular outcome as being an issue. What I do pick up on a little bit, I think there is some empirical evidence for, is the sort of feeding into polarization that we can get with social media, now I don't think that the evidence suggests for me that if you took you and me at a certain level of polarization and put us on social media, that we would have a massive increase in how polarized we felt.

But what social media does seem to do is amplify people's access to extreme material and basically the people who are more polarized get amplified in terms of the power of their voices, so my impression at least and I'm willing to be challenged on this, I'm not like married to this, I won't say this is the theory of everything. But my impression is that what's happening is not so much that the average person is becoming more polarized, that might be happening to some degree but I don't think that's the biggest issue. I think we're giving more Pope power to the most polarized people.

Nico: I think there's probably some studies that have been done to determine social media huge and level of extreme views or even, if I sit on last year when the George Floyd protests were happening, I was sitting on Twitter, I'll never forget it because I was happen to be at my bachelor party at the set. Yeah. And I was doom scrolling and my blood pressure was rising. Right. As I was seeing all these things happening throughout the country and it's hard to argue that social media wasn't having some sort of psychological, even physiological effect on me.

Chris: Yeah, I fully agree.

Nico: And you even talk about this a little bit, that just the incentives of social media and the easy access of it, you talk about this in your book, encourage a lot of it, right? Because it used to be, if you got angry at something you read, you had to sit down, take out your pen, take out your paper, write up your letter to the editor and pay the 50 cents for the stamp and put it in the mailbox. Now you 240 characters you can bang out in 20 seconds and then pat yourself on the back and go on with your day. It's just the access to be able to express yourself is easier.

This is one of the most disappointing things about social media. And this is getting a little bit off topic to me is there's a lot of people who I really respected in a pre social media age, who, as soon as their ad was unleashed on Twitter, I had much less respect for them, like a fear of him coming after me although we're an hour into this, I doubt I listened to it and it seemed to lab. I mean, he wrote The Black Swan and he wrote, he Fooled by Ran all these great books, amazing insights, but he's insufferable the law watch on Twitter.

All he does is pick fights with people and tell everyone else they're dumb but that's a whole separate argument. I wanted to ask you on the suicide point there are communities, not communities to help people who are seeking to come out of their suicidal depression but communities that actually help people commit suicide on the internet and there was that famous case a couple of years ago where I think it was a girlfriend of a guy, the guy was having suicidal thoughts and tendencies, unfortunately and the girlfriend was not helping him.

She was actually encouraging him to commit suicide and eventually he did, I think she was tried and found guilty. In America we have wide latitude for people to express themselves even if we find that, that expression is harmful at the margins. I mean, we allow the anarchist cookbook to be published for God's sake, right. How influential are those sorts of communities in pushing people over that very unfortunate edge? How damaging is this sort of expression these communities that prop up among people who are considering self-harm?

Chris: Yeah, that's a great question and of course the answer is sort of complicated but I just can't give simple answers but the area that I'm more familiar with actually is that they sort of look pro-anorexia websites, which is kind of a similar sort of issue and debate and so, the concern there is, of course that young people, particularly young women will go on these websites where they're encouraged to develop and or maintain, there are all these clues about how to hide it from your family and all kinds of other stuff.

Challenges about how thin you should be and so on and so forth and most of us would say like this isn't great. The evidence we have again is that for the average young woman goes on the website and it doesn't affect her at all. What does happen is possibly if you have a woman who already, or young woman teenager, or whatever who already has anorexia then what can happen sometimes is that if the person feels bad about it, feels guilty about it. Maybe guilty is not the right word, but it has some cognitive dissonance about it. I'm trying to think of the psychoanalytic word for it but basically finding people who are like-mind can reduce inhibitions to something, sort of re reduces the stigma of that –

Nico: But not everyone wanna be a part of a community, right? Not all communities are good for the self. I mean, you can talk about cult leaders in your book.

Chris: Right. Yeah. Well, people have this thought of identification. That's what I'm trying to think of, I'm having this thought, is it bad? And then you go on, you find someone likable who has the exact same thought and that convinced you well, my thought isn't that bad, I guess, I mean the most extreme version of this of course, when we used to have like, was it NAMBLA right?

Which is a north America, it was a pedophile organization. Right. It was people would worry, I think with legitimacy like, what if you have a pedophile who feels guilty, as you probably kind of should and just having these thoughts that are upsetting and they say well, I'm thinking of this but I also think I'm worried I might hurt someone and –

Nico: Somebody helped me essentially.

Chris: Yes and what you don't want is for someone to then say, oh no, no, no, it's all good, don't worry about it because then you may remove that stigma that you may remove that block that it's actually preventing them from doing something horrible. It's not gonna be like the average person goes onto this website and it's going to say, wow, I hadn't thought about suicide before but now it makes a lot of sense, in a sort of thing, but someone who's already maybe teetering on that edge.

It's not gonna be like the technology did it, it's gonna be connecting with another human being that, making that human connection and having that person give some sort of influence that is going to nudge them over the side is gonna argue against whatever barriers they were having that were preventing them from engaging in that harmful behavior and that's where I think there were legitimate concerns around some of that stuff, what percentage of suicide does that explain? Probably not very much, but maybe a small amount, so.

Nico: Yeah. I think those sorts of arguments are the biggest challenges and of course encouraging someone to commit suicide as that case demonstrated and if the facts bear it out is a crime. I mean, she was convicted but it's one of the challenges that free speech advocates have because you have people who are in distress, psychological states they find these communities who encourage self harm or harmful behavior. They have the right not only the free expression right but also the free association right, to associate rates around these shared ideas and we often think some more speech is the counter to bad speech, but these are closed communities, right?

There's no disconfirmation happening there. This is the sort of psychological hack you see throughout history is people are vulnerable psychologically and then people exploited, this is what happened in Myanmar, Germany. You talk about this in your book, too, right? Hitler hacked a vulnerability in German society and drove a big Panzer tank right through it so.

The last question I want to ask you is one that I've been flirting with since I took a statistics course in college. I was not a good math student, but I love statistics because of what it told me about society and I'll never forget my Professor, like the first day of class he drew the normal curve on the whiteboard, I might probably butchering the description of it but it's the curve found throughout society in a bunch of natural phenomena so like it's low on the edges and then it comes up like a hump and then it comes back down.

You could do it with the size of babies, most babies are seven pounds so they're up here at the top of the curve but at the end of the curve you'll get some 13 pound babies and you'll get some four pound babies, right but you see it in the size of tree trunks, you see it in behavior, you see it all over the place and when he told me this, I started to wonder, are the deviant behaviors that we see all over human history, you can never root them out because there will always be that curve and you can only just shift the curve, but you can't eliminate it. There's always going to be deviance in society.

There's always going to be the Mosaic Dunns and the Hitlers and there's always going to be, unfortunately, the people who have schizophrenia or who have suicidal thoughts and ideations and it created a lot more tolerance on my part but it also creates a question about free will, which you discuss in your book is like, if these sorts of people in these sorts of behaviorals are found throughout the world and they have to exist almost, what is there left for us to do about it but accept it. Have you thought about that?

Chris: Yeah, that's a great question. And a really complicated one and I'll try not to go on for like half an hour trying to answer it. But I think there are a few really interesting threads. It's important to point out there are some exceptions course of the bell curve, I mean there's some things like, even like violent crime, for instance, it doesn't work on a bell curve. That's all a lopsided, for sexual –

Nico: Yeah. There is like what they call the parade or principle. I don't know if that's a example, the idea that like 20% of people are responsible for 80% of the effect or, but maybe you could put that on a ball curve too.

Chris: Yeah. It’s this sort of concept of like population dynamics if you kind of think of like a typical trait and if we accept that most traits have some biological input to them, some genetic input to them, you are by nature gonna get a range of those things. We're not gonna get like absolute uniformity and largely speaking, thinking in terms of genetics, you don't want it. If you look at critters that have near uniformity in terms of their behavior, they don't do well. For the most part, koala bears, everybody loves koala bears, but all they eat is eucalyptus leaves. They’re doomed, I mean they’re kind of, I love –

Nico: If the eucalyptus leaves no longer exist, Darwin's could come in for them.

Chris: Yeah. Basically, so rigid critters tend to do less well than critters that have this kind of like Y range of things. Now that doesn’t mean you end up sometimes with, take a trait like aggression right, which is really kind of the one that a lot of people interested in the aggression works on a bell curve most of us are somewhat in the middle. If you like come up to me and poke me in the eye, I'm the little guy, I don't get any fights because I'll get my kicked but I'm not gonna just like shrug it off, I was like, oh, well it must have been an accident but most of us wouldn't hopefully be the one to do the poking in the eye, right. We wouldn’t be.

So, we're somewhere in the middle and being somewhere in the middle of aggressiveness is probably the most adaptive place under most circumstances which we currently live, you don't wanna be too passive, you just get rolled over and you don't want to be too aggressive because you're a criminal and you'll be thrown in jail so those are both non-adaptive, sort of extremes on this Belker but that could change. Right. So, what are the zombies attack?

All of the people from like 80% down of that curve are gonna die, and it's gonna be as the walking dead TV series pretty well demonstrated it's gonna be the most aggressive people who are going to survive. And we'll look –

Nico: I’ve never even thought about it that way, so although it's completely obvious is that the variations in behavior that you find on a bell curve throughout our environment throughout the world is an evolutionary necessity for species survival, essentially.

Chris: It is. Yeah. There's a lot of complexities built into this, but it usually is generally better to have more variation than less, so if we end up creating this utopia where everybody, I wish I in many ways morally think is a great idea if where we all just get along and we're all peaceful and there's no violence between humans, it's all sounds wonderful until the aliens come down and take over, right. You know what I mean? And then it's a terrible idea.

Sometimes when we have to think about that, the other aspect of it is sort of to address another point but the free will is, I'm something of a, I guess the word is a compatiblist that, I think that some aspects of freewill are compatible with determination and in other areas in that, so the example I sometimes use is that it absolutely is true that our genetics and our environment in many ways shape our behavior or attitudes and so on and so forth, we're not complete gossamer angels making up decisions willy-nilly as we go through the world.

So, for instance, I probably more than the average person even love donuts, this is absolutely true and probably a lot of that comes from my genetics. In fact, I have a lot of like weird tastings and tastes of versions and stuff around vegetables and fruits so I'm gonna have a terrible diet that I really just can't control so being directed towards donuts as opposed to broccoli, there's probably something that is biologically wired into me, right. On the other hand, I still have the choice to eat that donut or not so when I make the decision and I make this decision fairly regularly, should I have a goodie or should I not?

I still have some degree of capacity to make a decision. My biology motivates me towards one of those choices but I still left the compatiblist argument, right. There is this determination as sort of direct me towards one outcome more than the other one but I still have some capacity to make some decision between those two things that we might describe as basically being freewill so if I make the decision to eat the donut which I often do that is still my responsibility, I still have made that choice and I shouldn't just blow it off and be like well, genetically I'm an automaton and if I die early as a consequence so be it I never had any choice in the matter –

Nico: There’s still a bell curve in our normal curve for self control –

Chris: Impulse control.

Nico: Impulse control as well. You're two standard deviations away on the tail there your impulse control isn't gonna be good but someone based on what we know about bell curves needs to be on that at that standard deviation but of course, bell curves can change over time and the standard deviate, it could shift one direction or the other and the bell.

So, it's not like there's no control over what that looks like I guess, it's something I've always thought about, we could talk about it for an hour, you need to have some sort of tolerance for the extremes, because just the nature of the world is that the extremes going to always exist and you can't really eradicate them. But you can create systems. I moved my microphone away we're not done but we can create systems to kind of control them create the right incentives and stuff like, and that's more Cass Sunstein to work, on nudge –

Chris: Yeah. I was gonna say, yeah, I think, and of course you had to be realistic about the actual impact so I think like a lot of the promises of the nudge idea haven't really worked out as well as people thought but we're less knowledgeable than people had hoped. I know it's not, again, it's just a matter of having a certain degree of realistic expectations about how you can know. So, the idea of the brave new world is probably a utopian fantasy or dystopian fantasy, depending on how but yeah.

Nico: The nudge thesis, I mean, Cass Sunstein is nudge thesis seems to be a good moderate perspective. I hate to use the phrase social engineering but that's essentially what they're telling to do. It's benevolent in the sense that there's no compulsion, for example, having you automatically enroll in a 401k and you need to check the box to unenroll in it if you don't want to, rather than putting the burden on you to do the automatic enrollment when you start a new job of course you can get to much less benign subjects –

Chris: Yeah. I was going to start that assumption of a benign-ness, I don’t know if that's the right word.

Nico: I mean, the civil Libertarian is just by their nature anytime you mentioned the phrase “Social Engineering” but that’s kind of what nudge is. Get squeamish and rightfully so because social engineering has a horrid history in the world, but –

Chris: You could see it like stray from that a little bit, I think kind of going back to free speech issues a little bit too, I don't know whatever came of it but I know like in the UK they were very big on the nudge concept for a while, there was a movement, well not a movement, It was actually a proposed legislation essentially that they were going to make it such that when you bought a new computer that your computer had like a net nanny it came with like a net filter on.

So, that basically it would filter out any pornography was the main thing they were looking for and that, you could turn it off you but that was the nudge, right. Is that it would sort of nudge in the direction of not viewing porn as opposed to viewing porn but who gets to decide that, that's the direction we want. I think the idea that porn is inherently harmful as a fairly controversial one so who gets to decide that –

Nico: You talk about that a little bit in your book, you talk about how there's an inverse correlation between sexual aggression, rape sexual assault and pornography viewing, you have a graph. I had never seen that before, I thought that was fascinating. We could have gotten into the pornography debate in this conversation but now we're an hour and 20 minutes in so I think we probably should wrap it up but this has been a lot of fun. The book is How Madness Shaped History. This came out last year?

Chris: Yes. Came out right at the beginning of the pandemic, which is the best time to release a book.

Nico: Yes.

Chris: No it was the worst possible time to release a book –

Nico: I was reading it. You were writing during, you talked about how you were writing during the Donald Trump presidency and for some reason, I thought this came out this year and I was like arena. And I was like, it must've came out. It came out last year while I released a movie during a pandemic, so independent movie, so you can't do film festivals, you can't do distributions, our theaters are closed, you can't bring any of your friends to munch on popcorn, so it's like a solidarity there, brother.

Chris: It turns out you can't print books if nobody's working in the place that prints books.

Nico: I mean the paper shortage is a real deal thing. I mean there's supply chain issues all over the place but I remember when Greg was working on coddling, they couldn't keep up with the supply because they couldn't get paper to bind books but anyway, the book is How Madness Shape History. I encourage any history lovers, psychology lovers out there to check it out available wherever fine books are sold. Professor Ferguson, this has been a lot of fun. I'll have to do it again

Chris: Yeah. Awesome. This was fun. Thanks. Appreciate you having me on.

Nico: You’re welcome. This podcast is hosted and produced and recorded by me, Nico Perrino and edited by my colleague. Aaron Reese. You can learn more about the show at Twitter. We're on twitter.com/free speech talk. And we're also on facebook; @facebook.com/sotospeakpodcasts; we take feedback. So, if you've got some email, sotospeak@thefire.org, if you have any for Chris, I can send it along to him as well. And if you enjoyed this episode, please consider leaving us a review, take them on apple podcasts, Google play, Spotify, Stitcher, wherever you get the podcasts, they do believe it or not help us attract new listeners to the show because we go up in their rankings, which is fun. But until next time, thanks again for listening.