Table of Contents

Silenced at Saint Mary’s: Censorship and Academic Freedom Concerns Raised After Professor’s Firing

As the spring semester begins today at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota, a storm of controversy is brewing amid allegations the school unjustly censored a school play, fired the popular professor who wrote it, and is now demanding silence from students and faculty critical of the administration.

One thing is certain: Numerous Saint Mary’s students and faculty who worked with Professor David Hillman tell FIRE they want people to know about the man they call a dedicated and brilliant scholar who got students excited about the classics.

“It’s a total loss for the university,” said Judy Myers, a theater and dance professor who directed Medea: A Virgin’s Voice last fall and who hired Hillman, an adjunct classics instructor, to write an original translation of the script.

“Students love him,” Myers said of Hillman. “He gets great ratings, he gets along really well with the faculty that surround him, and students were enrolled in his classes, ready to take his classes next year.”

Dorothy Diehl, chair of the Modern and Classical Languages Department and Hillman’s boss, agreed. She called him “an excellent professor.”

“Never before in the sixteen years that I have been at Saint Mary’s have I seen such interest in Latin and Greek as there has been since he joined the department,” Diehl said.

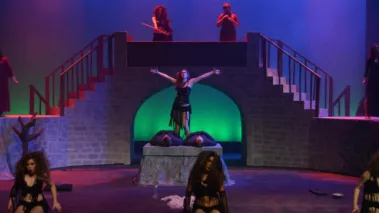

Medea, which Saint Mary’s newspaper The Cardinal called “a dark and moving story of greed, faith, and a mother’s love,” follows the story’s namesake as she seeks vengeance for her husband’s corruption by murdering their children.

But Hillman, a single father of two who also worked part-time as a janitor to earn extra income, said he was ousted from the small liberal arts school in the small southeastern Minnesota town of Winona after administrators grew uncomfortable with the play’s message.

Singled out were the phallic-shaped props, or fascina (pictured below), which—as Inside Higher Ed explained when it first reported on this story last month—were “[u]sed in the ancient world in certain rites and to ward off evil” and which “are supposed to embody the divine power of the phallus.”

As part of the play, cast members point fascina at audience members—an ancient practice Hillman says was used as “a means of holding a mirror up to the audience and confronting viewers with their lavish and corrupt lifestyles.”

Hillman says his version of Medea, a translation of the ancient Greek tragedy by Roman philosopher and dramatist Seneca, simply followed “the authenticity of the Etruscan examples that paved the way for Roman drama.”

That, Hillman says, was his job.

“The director [of Medea] hired me for authenticity,” Hillman told FIRE. “She said, ‘If we’re gonna do this, we’re gonna do it right. It’s going to be authentic.’ My job as the poet/translator was to maintain the historical integrity of the play.”

But administrators, led by Dean of the School of the Arts, Michael Charron, ultimately banned the fascina amid concerns they were too suggestive.

Not long thereafter, Hillman found himself terminated from the university on sexual harassment charges. They are charges Hillman denies, and ones he is certain must arise from his work on the Medea production. Hillman says administrators never fully described the charges to him.

“The head of H.R. called me at home to tell me that I was terminated from both jobs,” Hillman said of his work as a teacher and custodian. “I asked him what the findings of the [sexual harassment] investigation were when he called. He told me ‘I did not call you to answer that question.’”

Two termination letters obtained by FIRE are similarly vague, accusing Hillman of engaging in “unwelcome” conduct and “creating an intimidating, hostile and offensive learning environment” by singling out students “based on their gender.”

One of the letters was written by the university’s Title IX Coordinator, who, according to the letter, says she is “empowered to adjudicate the sexual harassment complaint” by herself. FIRE has been critical of this so-called "single-investigator model" for adjudicating sexual harassment complaints.

Now unable to make ends meet, Hillman said he has “been standing in lines for months at the local food pantry.” His daughter, whose asthma medication he can no longer afford without insurance, recently asked him if they would soon be “out on the streets.” For the first time, he said, he didn’t know what to tell her.

“I worked 40 hours a week for them cleaning vomit and clogged toilets, while designing and implementing the strongest language program the school has seen,” Hillman said. “I destroyed the caps on my class enrollment, and attracted interest from rectors in Wisconsin and Minnesota alike who had seen the effect of my teaching on their students.”

"A loose cannon on the faculty"

Members of the Saint Mary’s community tell FIRE that what happened to David Hillman—and what continues to happen to other members of the university community in the wake of the Medea controversy—is an affront to academic freedom.

“The props would not have been a part of the production if their purpose was frivolous,” said Anne Colling, a Saint Mary’s senior who acted the title role of Medea in the play. “These props, however, represented sacred pieces used in religious rites in the culture we were portraying. Many of those rites are at the heart of Medea, though it may not be apparent at first glance.”

“As artists, it is our duty to the audience to portray the full truth so that they can deduce meaning, have complete understanding, and come to conclusions,” Colling said. “With censorship in the way, that is difficult—impossible even.”

Colling said Hillman’s passion for his work may have cost him his job.

“I think that passion can catch people off-guard,” she said. “He is not afraid to bring up uncomfortable, untalked-about topics that are relevant. This is what we should want in teachers. But straying from textbook learning and exploring unpopular ideas, I think, made the administration nervous. They may have viewed him as unpredictable and outspoken and did not want to have a loose cannon on the faculty.”

Myers, the play’s director, expressed similar concerns.

“I think there were some people that felt like they needed to put some controls down. To rein in me, to rein in the message of the play, to presume that the audience could only take so much. To presume that students should only be exposed to so much,” Myers said. “I think people got nervous in terms of what kind of feedback they might get: whether it was letters of audience members to the president, or donors not wanting to give money because something might have been too … edgy, for them, I guess ... to choose my words carefully.”

Choosing your words carefully is important at Saint Mary’s.

"Truth and knowledge"

Saint Mary’s, while a private Catholic school, promises students a “transformational and innovative university,” dedicated to “truth and knowledge.” The faculty handbook explicitly commits the university to academic freedom:

Institutions of higher education are conducted for the common good and not to further the interests of either the individual or the institution as a whole. The common good depends upon the free search for truth and its free exposition. Academic freedom is essential to these purposes and applies to both teaching and research. … Academic freedom in teaching is fundamental for the protection of the rights of the teacher in teaching and of the student to freedom in learning.

[...]

The faculty member is entitled to freedom in the classroom in discussing her/his subject[.]

In a statement earlier this week, Saint Mary’s Assistant Vice President for Brand Management Stacia Vogel assured FIRE that “Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota absolutely, unequivocally supports freedom of speech.”

Myers, Medea’s director, says otherwise.

“Either [administrators] are not reading their handbook, or they don’t believe in it, or there are certain limits and controls they are going to put on that statement,” Myers said.

A policy that contradicts the school’s claimed commitment to free speech and academic freedom is the university's overly broad sexual harassment policy, which sweeps within its ambit protected speech, such as “humor” of a sexual nature, or anything a listener might subjectively find “unwelcome” or “offensive.”

Specific examples of sexual harassment under the policy include “suggestive or insulting sounds,” “sexual innuendo,” and “humor and jokes about sex or gender-specific traits.”

How could a professor teach an ancient Greek tragedy’s themes about sexual innuendo without discussing them? Saint Mary’s faculty wishing to teach that subject, or any subject implicating sex or gender, do so at their peril.

FIRE has warned for years that such policies can be abused and used as pretext to get rid of faculty members with whom administrators simply disagree. Saint Mary’s professors tell FIRE that is exactly the kind of situation in which David Hillman found himself.

Vogel, the Saint Mary’s spokesperson, cited the sexual harassment claim against Hillman in response to his allegation that the university violated his rights to academic freedom.

“The issue at hand is not about free speech,” Vogel said. “It’s about an unhappy former employee who is lashing out at the university because he was not rehired due to wrongful behavior.“

“We are quite certain his claims against the institution represent a lack of his ownership of inappropriate actions,” Vogel said. “We take employee misconduct and sexual harassment claims very seriously. When claims against an employee are made at Saint Mary’s, they are investigated and acted upon.”

Dorothy Diehl, the classics chair, disputes that account.

“I was told that because [Hillman’s] was an open contract it could be ended at anytime with no reason needed,” Diehl told FIRE in an email. “I then asked the HR director whether the sexual harassment allegation against Dr. Hillman had been proven and was told that it was still under investigation. So, I asked how he could be fired if the allegation had not yet been proven and was again told by the dean that an open contract could be ended at any time without reason given.”

"The birthplace of free speech"

David Hillman says it is ironic that administrators would choose to censor a play written in an era where free speech and censorship were major themes.

“I had been teaching [the students] for a while that the stage was the first place of free speech, the birthplace of free speech in antiquity,” Hillman said, adding that administration’s attempt to censor the play “was almost as if the play was coming alive right before their eyes.”

Hillman thinks it’s not just the phallic images, but that the underlying anti-greed message of the play was “offensive” to an administration he says is more concerned with the Saint Mary’s “brand” than its students’ education.

Saint Mary’s denied Hillman’s allegations that it’s an institution overly concerned with controlling its public image, or the work of its faculty.

Dean Michael Charron told FIRE via email he would not “dignify the comments of a clearly disgruntled employee with a point-by-point response.”

But, he wrote, “I can say this: I am an advocate of free speech, and I'm proud of the work our institution does to ensure academic freedom. I know this translates to a vibrant and meaningfull [sic] educational experience for our students.”

He added, “I'm baffled that Mr. Hillman thinks an anti-greed message would harm our brand. That seems quite odd.”

The director, Myers, said she doesn’t know the administration’s motives beyond their expressed concern over the play’s props, but said the move had academic freedom implications for her as a professor.

“For me, it was much more of a professional overstepping and control that I thought was completely unnecessary and untrusting of someone who’s been there for 17 years and who has the status of full professor,” Myers said.

Myers, and other faculty and students who spoke to FIRE, said Saint Mary’s spin control in the wake of the controversy has been alarming.

“It also had to do with students and the way they were treated,” Myers said, referencing a meeting held by Dean Charron on the eve of the play’s opening that was meant to answer questions about the removal of the props. She said Charron ultimately told the students not to ask any questions or further discuss the matter.

“I find it unconscionable to silence students and to not let them ask questions,” Myers said. “Or, when they do ask questions, not to tell them the truth.”

When Myers and Hillman offered an explanatory editorial about Medea to the school newspaper, that was also subjected to prior review by Vice President of Academic Affairs Donna Aronson.

“She asked to see it,” Myers said. “When she asked for revisions, I dropped it.”

Aronson did not respond to FIRE’s repeated request for comment.

"A scarlet letter"

Hillman said he’s not sure where to go from here. Aside from an offer to write a book chapter, he’s out of both his teaching and custodial jobs.

“I’m afraid that my career is ruined. Because once you’ve been accused of something like sexual harassment, not many HR departments are going to hire you. You’re a risk. It’s a scarlet letter. Honestly,” he said, “I know that my future is not bright. But at the same time, my research is valuable. Right now, I don’t know what the future holds.”

But he said he’s not sorry for doing what he said was not simply his job, but a calling of historical importance.

“My responsibilities are to the ancient Greek and Latin texts,” he said. “I have to remain faithful to that. If I lose the texts, I’m no longer a scholar.”

“There’s something under the surface here that kind of represents everything we classicists are taught about Western civilization,” Hillman said. “That we have these plays and we have these beautiful poems and we have these works, because people were willing to stand up in the face of tyranny and preserve them. And to me, that is what is most important here.”

Will he miss teaching?

“Teaching is everything to me,” Hillman said. “It’s what drives me to do what I do. So, will I miss it? It’s more than will I miss it. It’s what gives me life, to be able to bring this stuff to students. And I won’t be able to do that.”

Hillman’s final request to FIRE echoed similar ones from the Saint Mary’s students and faculty interviewed for this story, all of whom thanked FIRE or “taking up this issue, for “looking into this,” for “covering this” story:

“Please tell people what is happening.”

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

Can the government ban controversial public holiday displays?

The trouble with banning Fizz

FIRE's 2025 impact in court, on campus, and in our culture