Table of Contents

2021 College Free Speech Rankings

On September 21, 2021, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, College Pulse, and RealClearEducation released the second annual College Free Speech Rankings. The 2021 rankings are based on the voices of over 37,000 currently enrolled students at over 150 colleges.

Executive Summary

In 2020, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), College Pulse, and RealClearEducation published the first-ever comprehensive student assessment of free speech on American college campuses: the College Free Speech Rankings. For the first time, prospective college students and their parents could systematically compare current students’ understandings of the level of tolerance for free speech on campus. We now present the 2021 Campus Free Speech Rankings.

Much has happened since the collection of last year’s data in April and May of 2020. The pandemic kept many students off campus. Professors, administrators, and students on many campuses moved their primary mode of communication and instruction online. Outside of the classroom, campus life transformed.

For some, the move to online learning allowed them to more comfortably and fully express themselves, since asynchronous online communication gave them more time to consider their points before posting them. For others, speaking online in virtual forums is a far cry from expressing their ideas in real-life organizational meetings and classrooms with peers, professors, and teaching assistants.

Despite being physically apart for the majority of the 2020–2021 academic year, students and faculty members were sanctioned because of their expression even more frequently than before. This report shows that the average overall score of 59.53 was higher than the average overall score of 52.72 in 2020. While this is somewhat encouraging the average overall score still does not represent a passing grade in a college course.[1]

This report builds on the 2020 assessment by including more than 150 colleges, nearly tripling the previous sample. These rankings are available online, along with more information to compare colleges on an interactive dashboard (speech.collegepulse.com). The dashboard helps prospective students and their parents understand the campus climate at colleges they are considering. Professors, administrators, staff, and current students also can use these rankings to better understand the student experience on their campuses by exploring which topics are most uncomfortable for students to discuss openly, campus by campus, and which groups feel most ready to do so.

FIRE, a nonprofit organization committed to free and open inquiry at colleges and universities in the United States, in partnership with RealClearEducation, commissioned College Pulse to survey students at 159 colleges about students’ perceptions and experiences regarding free speech on their campuses. Fielded from February 15 to May 30, 2021, via the College Pulse mobile app and web portal, the survey included 37,104 student respondents who were currently enrolled in four-year degree programs.

Key findings include:

- Claremont McKenna has the highest score on the 2021 College Free Speech Rankings. The University of Chicago, the University of New Hampshire, Emory University, and Florida State University also rank highly.

- DePauw University has the lowest overall score on the Free Speech Rankings for the second year in a row, confirming its place at the bottom. Marquette University, Louisiana State University, Boston College, and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute are near the bottom of the rankings.

- More than 80% of students reported self-censoring their viewpoints at their colleges at least some of the time, with 21% saying they censor themselves often.

- More than 50% of students identified racial inequality as a difficult topic to discuss on their campus.

- Two in five (40%) students said they were comfortable publicly disagreeing with a professor, down 5 percentage points from last year.

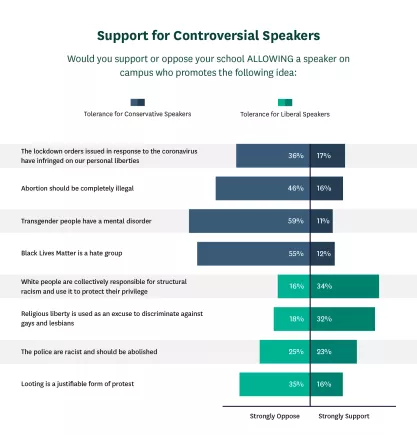

- There are wide differences in support for the speaking rights of controversial speakers on college campuses, ranging from a low of only 11% of students strongly supporting the rights of a speaker with the message, “Transgender people have a mental disorder,” to a high of 34% of students strongly supporting the rights of a speaker with the message, “White people are collectively responsible for structural racism and use it to protect their privilege.” In each case, though, large majorities do not strongly support the speaking rights of controversial speakers.

- Political ideology[2] was strongly correlated with tolerance or intolerance of controversial conservative speakers[3] and liberal speakers.[4]

- Two-thirds of students (66%) say it is acceptable to shout down a speaker to prevent them from speaking on campus, up 4 percentage points from last year.

- Almost one in four (23%) say it is acceptable to use violence to stop a campus speech, sharply up 5 percentage points from last year’s 18%.

- Only about one-third (32%) of students agree that their college administration makes policies about free speech either very or extremely clear to the student body.

About Us

About College Pulse

College Pulse is a survey research and analytics company dedicated to understanding the attitudes, preferences, and behaviors of today’s college students. College Pulse delivers custom data-driven marketing and research solutions, utilizing its unique American College Student Panel™ that includes over 500,000 undergraduate college student respondents from more than 1,500 two- and four-year colleges and universities in all 50 states.

For more information, visit collegepulse.com or @CollegeInsights on Twitter.

About FIRE

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to defending and sustaining the individual rights of students and faculty members at America’s colleges and universities. These rights include freedom of speech, freedom of association, due process, legal equality, religious liberty, and sanctity of conscience—the essential qualities of liberty.

For more information, visit thefire.org or @thefireorg on Twitter.

About RealClearEducation

RealClearEducation is dedicated to providing readers with better, more insightful analysis of the most important news and education policy issues of the day. RealClearEducation is part of the RealClear Media Group, which includes RealClearPolitics and more than a dozen other news websites. RealClear’s daily editorial curation, public opinion analysis, and original reporting present balanced, nonpartisan news coverage that empowers readers to stay informed.

For more information, visit RealClearEducation.com or @RealClearEd on Twitter.

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude goes to Sean Stevens and Anne Schwichtenberg for authoring this report, Sam Abrams for help with questionnaire design, Brianna Richardson for support with data analysis, Angela C. Erickson for support with data validation, and Adam Kissel and Komi German for editing.

Robert Shibley

Executive Director, FIRE

Methodology

The College Free Speech Survey was developed by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), RealClearEducation, and College Pulse. College Pulse administered the survey. No donors to the project took part in the design or conduct of the survey. The survey was fielded from February 15 to May 30, 2021. These data come from a sample of 37,104 undergraduates who were currently enrolled full-time in four-year degree programs at 159 colleges and universities in the United States. The margin of error for the U.S. undergraduate population is +/- 1 percentage point, and the margin of error for college student sub-demographics ranges from 2 to 5 percentage points.

The initial sample was drawn from College Pulse’s American College Student Panel™, which includes more than 500,000 verified undergraduate students at more than 1,500 different two- and four-year colleges and universities in all 50 states. Panel members are recruited by a number of methods to help ensure student diversity in the panel population, including web advertising, permission-based email campaigns, and partnerships with university-affiliated organizations. To ensure the panel reflects the diverse backgrounds and experiences of the American college population, College Pulse recruits panelists from a wide variety of institutions. The panel includes students attending large public universities, small private colleges, online universities, historically Black colleges such as Howard University, and religiously affiliated colleges such as Brigham Young University.

College Pulse uses a two-stage validation process to ensure that all its surveys include only students currently enrolled in two-year or four-year colleges or universities. Students are required to provide a .edu email address to join the panel and, for this survey, had to acknowledge that they were currently enrolled full-time in a four-year degree program. All invitations to complete surveys are sent using the student’s .edu email address or through notification in the College Pulse app that is available on iOS and Android platforms.

College Pulse applies a post-stratification adjustment based on demographic distributions from multiple data sources, including the 2017 Current Population Survey (CPS), the 2016 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), and the 2018–19 Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). The post-stratification weight rebalances the sample based on a number of important benchmark attributes, such as race, gender, class year, voter registration status, and financial aid status. The sample weighting is accomplished using an iterative proportional fitting (IFP) process that simultaneously balances the distributions of all variables. Weights are trimmed to prevent individual interviews from having too much influence on the final results.

The use of these weights in statistical analysis ensures that the demographic characteristics of the sample closely approximate the demographic characteristics of the target populations. Even with these adjustments, surveys may be subject to error or bias due to question wording, context, and order effects.

For further information, please see https://collegepulse.com/methodology.

The College Free Speech Rankings are based on a composite score of seven sub-components described in detail below: Openness, Tolerance for Conservative Speakers, Tolerance for Liberal Speakers, Administrative Support for Free Speech, Comfort Expressing Ideas, Disruptive Conduct, and FIRE’s Speech Code Rating. To create an “Overall Score” for each college, the seven sub-component scores are added for a maximum possible score of 100 points. A college’s Overall Score is the average score of the students surveyed at that college. Higher scores indicate stronger environments on campus for free speech and expression.

Openness: Students were asked which topics, if any, were difficult to have open conversations about on campus. Options included: Abortion, Affirmative action, China, Climate change, Coronavirus, Economic inequality, Gender inequality, George Floyd protests, Gun control, Immigration, the Israel/Palestinian conflict, Racial inequality, Sexual assault, Social media deplatforming, and Transgender issues. Students also could select an option stating that none of these issues were difficult to discuss. These options were reverse coded such that when students selected fewer issues as difficult to discuss, schools received a higher score. The highest possible Openness score is 15, which indicates a student response that no issues are challenging to discuss on campus.

Tolerance for Liberal Speakers: Students were asked how much they support or oppose allowing different speakers to speak on campus, even if they did not personally agree with the speaker’s message. Students evaluated eight speaker topics, which were balanced to be equally controversial among liberal or conservative students. Survey items for liberal speakers included: “Religious liberty is used as an excuse to discriminate against gays and lesbians,” “White people are collectively responsible for structural racism and use it to protect their privilege,” “Looting is a justifiable form of protest,” and “The police are racist and should be abolished.” Options ranged from “strongly support” to “strongly oppose” on a four-point scale. Options were coded such that more support for speakers received higher scores. The highest possible score for this component is 16 points.

Tolerance for Conservative Speakers: Similarly, students were asked how much they support or oppose allowing conservative speakers to speak on campus, including the items,“Black Lives Matter is a hate group,” “The lockdown orders issued in response to the coronavirus have infringed on our personal liberties,“ “Abortion should be completely illegal,” and “Transgender people have a mental disorder.” Options were coded such that more support for speakers received higher scores. The highest possible score for this component is 16 points.

Administrative Support for Free Speech: This component comprised scores on two items: “How clear is it to you that your college administration protects free speech on campus?” and “If a controversy over offensive speech were to occur on your campus, how likely is it that the administration would defend the speaker's right to express their views?” Options ranged from “extremely likely” to “not at all likely” on a five-point scale, with higher scores representing greater perceived support for free speech and a maximum score of 10.

Comfort Expressing Ideas: This component comprised scores on six items. Five items asked students how comfortable or uncomfortable they would feel doing the following: “Publicly disagreeing with a professor about a controversial topic,” “Expressing disagreement with one of your professors about a controversial topic in a written assignment,” “Expressing your views on a controversial political topic during an in-class discussion,” “Expressing your views on a controversial political topic to other students during a discussion in a common campus space, such as a quad, dining hall, or lounge,” and ”Expressing an unpopular opinion to your fellow students on a social media account tied to your name.” Options ranged from “very comfortable” to “very uncomfortable” on a four-point scale, with higher scores representing greater comfort. The sixth item scored responses to the question, “On your campus, how often have you felt that you could not express your opinion on a subject because of how students, a professor, or the administration would respond?” Options ranged from “never” to “very often” on a five-point scale, with less frequent indication of inhibition receiving a higher score. The scores across these six items were scaled to a maximum of 25 points.

Disruptive Conduct: Students were asked how acceptable or unacceptable different kinds of activities to protest a campus speaker were. These included: “Shouting down a speaker or trying to prevent them from speaking on campus,” “Blocking other students from attending a campus speech,” and “Using violence to stop a campus speech.” Options were scored on a four-point scale ranging from “always acceptable” to “never acceptable,” with less acceptance of disruptive conduct receiving higher scores. The highest possible score was 12.

FIRE Speech Code Rating: FIRE rates the written policies governing student speech at over 475 institutions of higher education in the United States. Three substantive “Spotlight” ratings are possible: Red, Yellow, or Green. A rating of Red indicates that the institution has at least one policy that both clearly and substantially restricts freedom of speech. Colleges with this rating received a score of -6 points. Colleges with Yellow ratings have policies that restrict a more limited amount of protected expression or, by virtue of their vague wording, could too easily be used to restrict protected expression. This rating received a score of 0. The policies of an institution with a Green rating do not seriously threaten speech, although this rating does not indicate whether a college actively supports free expression. This rating received a score of 6. Finally, a fourth rating, Warning, is assigned to a private college or university when its policies clearly and consistently state that it prioritizes other values over a commitment to freedom of speech. Colleges with this rating were scored like Red schools and received a score of -6. Their scores are presented separately.

Overall Score: To create an Overall Score for each college, the seven components were added together, for a maximum possible score of 100. The Overall Score for each college is the average score of the entire student body surveyed at that college, including the College Pulse weighting described above.[5] The average Overall Score score was 59.53, and the standard deviation was 3.81.

Overview

Last year, FIRE launched a first-of-its-kind tool to help high school students and their parents identify which colleges promote a free exchange of ideas. The response to the College Free Speech Rankings and online tool was overwhelmingly positive. They helped prospective students see what a large number of current students actually said about the campus climate for open discussion and inquiry, comparing college against college, without needing to step foot on any campus in the midst of a pandemic.

The 2020 Rankings were comprehensive assessments of only 55 colleges, however. This year, the College Free Speech Rankings survey nearly tripled to include the same 55 colleges plus 104 more, bringing the total number of ranked colleges to 159.

Again this year, the College Free Speech Rankings Dashboard (speech.collegepulse.com) is available on the College Pulse, FIRE, and RealClear websites. The Dashboard offers a unique tool to compare schools across their free speech rankings plus a set of other factors that students find important, such as cost and proximity to home.

We also heard from colleges and universities that the rankings helped them better understand their campus climate in order to improve it. Similarly, professors and staff were better able to understand which topics were difficult for students on their campus to discuss.

The body of this report contains three further sections. First, it presents analyses of the free-speech attitudes and experiences of the college students surveyed. Next, it provides the College Free Speech Rankings. Finally, to offer additional richness in comparing colleges about their free-speech environments, we profile five colleges in greater detail.

National Data

The 2020–2021 academic year was unlike any in modern history. Millions of students remained out of their dorm rooms and off of their college campuses while the country continued to hide from the COVID-19 virus. This year’s survey shows that the vast majority of students took classes this spring primarily online, with 80% of students reporting that most of their instruction was virtual rather than in person. Only 2% of students reported that they had exclusively in-person instruction.

The change from classroom discussions to a year’s worth of mostly online interaction cannot be ignored when understanding how students perceived their academic and social experiences. Student opinion was mixed with regard to whether online instruction facilitated or hampered their expression. While one-third of students (30%) reported that participating online was the same as for in-person classes, a plurality (42%) said that exchanging ideas online was more difficult than doing so in person. The remaining quarter of students (27%) said it was easier to share their opinions online than in person.

Self-Censorship

Despite these varied experiences, a majority of students reported censoring what they say at their colleges. When asked, “On your campus, how often have you felt that you could not express your opinion on a subject because of how students, a professor, or the administration would respond?” more than 80% of students reported some amount of self-censorship, with 21% of students reporting that they did so “fairly often” or “very often” and 62% saying that they censor themselves “rarely” or “occasionally.”

While differences in self-censorship between male and female students, by race, and by class year are limited, there are marked differences in the area of political orientation. Among students who identify as liberal or who identify as neither liberal nor conservative, the rate of reporting no self-censorship was the highest, at 19%. Just 12% of respondents who identify as middle of the road reported no self-censorship, and the proportion for conservatives was only 9%.

What do students mean when they think of self-censorship? For many students, merely sharing a perspective is the least of their worries; they say they are concealing their very identities from their classmates, professors, and others on campus.

“Though I hold liberal views, sometimes in some topics my views are more conservative and I'm afraid of being labeled something I am clearly not.” –Student at Stony Brook University

“In a class discussion after a controversial ‘racist’ incident involving a black student and public safety officers, I wanted to express that I didn't think the actions of the officers were entirely unjustified. I felt like I couldn't say this because everyone around me was saying how racist it was (even though none of these students were black but I was).” –Student at Barnard College

“I am scared to be openly transgender or anti-police/progressive in general due to how violent some people can be and the fact that ASU tends to protect harassment and conservativism.” –Student at Arizona State University

Difficult Topics of Conversation

Students were asked specifically which issues were difficult to discuss at their college. This year’s survey presented 15 hot-button issues for students to select. On average, a notable portion of students identified 10 topics. Of these, racial inequality was identified by more than half of the respondents (51%), and abortion was selected second most frequently (46%). Gun control (44%), George Floyd protests (43%), and transgender issues (42%) rounded out the top five.

Meanwhile, there were some controversial issues that students did not consider difficult to discuss. Only about 1 in 5 students reported China, social media deplatforming, and climate change as difficult to discuss.

In this area students’ responses differed significantly by race, gender, sexual orientation, political orientation, and whether the college is public or private.[6] For example, female and non-binary students much more often selected sexual assault (both 42%) than males (34%). Also, white students much more often than students of color selected gun control (46% vs. 41%). And there is a 13 percentage-point gap between students attending private colleges and those at public colleges in selecting abortion, with 51% of students at public colleges reporting that abortion is a difficult topic to discuss compared to only 38% of students at private colleges.[7]

There were several cleavages between students of different political orientations. On the whole, students who identify as conservative reported much more difficulty discussing a range of issues on campus. While both liberal and conservative students selected racial inequality most frequently, 59% of conservative students selected it, while less than half (48%) of liberal students did. Similarly, more than 50% of conservative students selected abortion, racial inequality, gun control, the George Floyd protests, and transgender issues.[8] Overall, conservative students more often identified all but three topics as difficult to discuss than their liberal counterparts (the three are sexual assault, the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, and economic inequality). On average, conservative students selected topics about 8 percentage points more often than liberal students.

How comfortable are students engaging in expressive behavior?

Only a minority of students reported feeling very comfortable doing any of the following: “publicly disagreeing with a professor about a controversial topic” (12%), “expressing an unpopular opinion to your fellow students on a social media account tied to your name” (13%), or “expressing your views on a controversial political topic during an in-class discussion” (16%). Students slightly more often reported feeling very comfortable sharing their opinions in public campus facilities such as a dining hall or on the quad (22%) or to a professor in writing (20%), but the majority of students felt uncomfortable doing any of these activities at their college.[9]

One student from Arizona State University wrote:

More recently it has been difficult to express my opinions, considering that most schooling is done online and my main focus is my education rather than having intellectual conversations regarding the modern political climate in the United States. However, in the past when school was instructed on campus I experienced hesitancy to share my views for fear of disapproval of my peers. Often we would have speakers come to campus and discuss their interpretation of Biblical teachings and I might have agreed with some points made and disagreed with others but I did not voice these opinions as a large majority of students were often found reprimanding and ridiculing the speakers on multiple occasions. As there was already an abundance of opposition against these kinds of speakers I did not feel comfortable expressing support, in order to evade being a target of that same disrespect.

Male students more often reported feeling very or somewhat comfortable publicly disagreeing with a professor than their female counterparts (45% vs 35%). Students who identified as non-binary were the most likely to feel comfortable publicly disagreeing with their professors, with 49% reporting that this was either very or somewhat comfortable for them. Similarly, while 40% of male and female students were very or somewhat comfortable sharing an unpopular opinion on a social media account, 47% of non-binary students would feel comfortable doing so. Several open-ended responses from non-binary students showcased their comfort in their campus expression:

“I have never not expressed my opinion.” –Auburn University student

“The only time I do not feel I could express my opinion on campus is when I don’t feel informed enough.” –Bard College student

“Never. I’m non-violently vocal about my identity and views on society. I will throw hands via strongly worded essays with the Binghamton review if need be though.” –Binghamton University student

“I don’t have a specific instance. I am trans and bisexual, and I refuse to entertain any argument about my rights as a person. I deserve rights, and if people disagree I cut them out of my life. I won’t change their minds, I won’t hurt myself in the process of attempting the impossible.” –Claremont McKenna College student

Who are the most controversial speakers?

Students are concerned not only about their own speech but also about the speech of invited guests. Each year, thousands of speakers visit college campuses to give lectures and talks. Yet many such talks have led to controversy, demands for silencing, or even official disinvitations.[10] Last year, the 2020 survey asked about six hypothetical speakers with controversial messages. The 2021 survey added two additional controversial speakers. Students were asked how much they supported or opposed allowing a speaker to express the following views:

- “Religious liberty is used as an excuse to discriminate against gays and lesbians.”

- “White people are collectively responsible for structural racism and use it to protect their privilege.”

- “Looting is a justifiable form of protest.”

- “The police are racist and should be abolished.”

- “Black Lives Matter is a hate group.”

- “The lockdown orders issued in response to the coronavirus have infringed on our personal liberties.”

- “Abortion should be completely illegal.”

- “Transgender people have a mental disorder.”

The question was merely about allowing a person with each message to speak on campus, in order to avoid confusion about whether the students themselves supported the positions listed. Nevertheless, the speakers naturally cluster into those whose rights conservative and conservative-leaning students on the one hand, or liberal and liberal-leaning students on the other hand, more often support, and ideological gaps regarding these speakers are wide.

The responses are ominous for supporters of free expression on campus. Only 17% of students strongly supported allowing a speaker saying, “The lockdown orders issued in response to the coronavirus have infringed on our personal liberties,” and 36% of students strongly opposed letting this speaker express this view on campus. There was much more opposition to allowing a speaker who says, “Transgender people have a mental disorder,” with 59% of students strongly opposed, or a speaker saying that Black Lives Matter is a hate group, with 55% strongly opposed. Allowing the message, “Looting is a justifiable form of protest” received strong support from only 16% of students, with 35% of students strongly opposed.

Generally, students showed much greater intolerance and much less support for allowing speakers with conservative messages on campus. Speakers with liberal messages generally had much more support for their expression, but full tolerance remained low. For example, 34% of students strongly supported allowing a speaker with the message, “White people are collectively responsible for structural racism and use it to protect their privilege,” with 16% strongly opposed. Similarly, a speaker who says, “Religious liberty is used as an excuse to discriminate against gays and lesbians” had strong support for speaking from 32% of students.

On average, across the four hypothetical conservative speakers, only 14% of students reported strong support for allowing them to speak. In contrast, 26% strongly supported allowing the speakers with liberal messages. A plurality of students at least somewhat supported allowing three of the four speakers with liberal messages. Only two messages garnered strong support for being allowed by at least one-third of students: “White people are collectively responsible for structural racism and use it to protect their privilege” (34%) and “Religious liberty is used as an excuse to discriminate against gays and lesbians” (32%).

Some students, in their survey comments, mentioned allowing the speech of both a controversial speaker and a protest against the speaker:

“I do not care about free speech in that it is something that needs to be doggedly protected no matter what. The ‘controversial’ reaction to a potential speaker is ‘free speech’ just as much as the original speech was. I care that the administration and the campus community advocate for opinions that are not harmful or hurtful to the community at large and make it clear that they value their students’ safety and wellbeing.” –Barnard College student

What are students’ views about their administration’s support for freedom of speech on campus?

The 2020 data showed that despite discomfort speaking on campus, many students agreed that their administration did a good job communicating its support for free speech. Similarly, in the unique circumstances surrounding the mostly remote period of online instruction, students mostly agreed that their colleges supported open expression. This year, more than 73% of students reported that their college made free speech policies at least moderately clear to the student body, with only 12% saying that the policies were not at all clear. Likewise, more than 7 in 10 students (72%) reported that if a controversy over free speech were to happen at their college, the administration would be at least somewhat likely to side with the speaker in question. Only 7% of students said it was not at all likely that their college would defend the speaker.

Race, gender identity, and whether the college was a public or private institution did not determine remarkable differences in this area, but gender and class year did.[11] Male students reported much more often than female students that their college was “not at all clear” about its speech policies (15% vs. 9%). Similarly, juniors and seniors were less likely than freshmen and sophomores to agree that their college made its speech policies clear. While 77% of freshmen reported that their college had at least somewhat clear policies, this was true for only 69% of college seniors. Similarly, juniors and seniors more often reported that their college would be “not very” or “not at all likely” to defend a controversial speaker compared to freshmen and sophomores (30% vs. 26%).[12] It seems that additional years on campus may add examples of cases when the college did not defend a speaker.

Last year, the University of Chicago outperformed all other colleges surveyed in this area, and this year the university again took the top spot out of 159 colleges. Just over half (13) of the schools ranked in the top 25 have endorsed the “Chicago Principles,” a nationwide exemplar of a speech-protective university policy. One student at the University of Chicago wrote:

“I have luckily never felt like I had to hide my opinions (political or not) on this campus. I understand that we are all different people from different backgrounds and inherently we might disagree with each other on some topics. And I think that most of the people here also understand that fact.”

At the bottom, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute received the lowest score for administrative support of free speech. Students wrote:

“We can voice opinions about the administration but the administration ignores most of the outrage against their policies.”

“The recent deaths of International Students during the pandemic have surfaced on our college campus in light of the Anti-Asian/AAPI hate and violence that has pervaded society and I have consistently been dissuaded by members of the Administration and Student Government to voice support for this demographic within the student population.”

"The culture at RPI is very stereotypically liberal with very little heard disagreement. I know people of many various opinions but most who vary significantly from the zeitgeist will not vocally share. Students also usually do not care to listen to opposing viewpoints and the university does little-to-nothing to counter this outside of some rare as this is a safe space of opinions bubbles. I also do not trust the administration to support free speech at all if something truly controversial is said in a manner that will conduce any sort of publicity."

Some respondents perceived that students who serve as representatives of the student body have a privileged voice, having frequent opportunities to interact with the administration. Those who represent students are not so sure. A student at Johns Hopkins University wrote:

“During the COVID-19 response meeting among student leaders, the administration had various representatives in each group. I felt after these representatives shared their opinions I could not freely share mine as they were in a position of power.”

But a student at Macalester College wrote:

“The Macalester College administration is fairly unresponsive to student critique/feedback on how to better their operations so that the school better serves the needs of the student body. I have worked with several groups of students to bring issues to light with minimal success. Administration tends to demand concrete steps if you voice broad frustrations, and talk about the lack of feasibility when you provide concrete steps. Macalester is not a conducive place to my mental wellbeing because of this.”

What controversial forms of disruptive conduct are acceptable on campus?

Regarding the forms of disruptive conduct students find acceptable to use against speakers, the 2021 data showed that although most students opposed violent tactics, the percentage of students who found violence never acceptable declined compared to last year. In 2020, 18% of students said the use of violence in protest was acceptable to some degree. This percentage increased to 23% in 2021. Students also were more accepting of other forms of disruptive conduct, with 66% saying that it was acceptable to shout down speakers to prevent them from speaking, compared to 62% in 2020, and with 41% who said blocking other students from attending a campus speech was acceptable, compared to 38% in 2020. One student at Case Western Reserve University wrote:

“About a year ago a pro-life student organization was formed and there was some controversy over whether or not they should be allowed on campus or be able to use school funds allotted for student clubs and groups. I thought this was a rather complex issue related obviously to abortion rights but also the free speech of that group. Some of my closest friends were really upset with me for expressing concerns with totally blocking out this group's voice (even though I personally disagree with their goals) for fear that other student groups could also be ‘silenced.’ It is hard to delve into the deeper layers of issues like this, but I do not think the reason I felt like my opinion was not valued had anything to do with the school's actions. Sometimes it is hard to converse about sensitive topics when there is some gray area because some students do not agree that this gray area exists.”

“As a member of the BC Republicans last year one of our speakers had many protesters outside the room. They were banging on the walls and we had to be ushered out of the room by police at the end of the talk. I felt that my ability to speak in the future was limited because I was afraid of dealing with something like that again.” –Boston College student

Freedom of speech at “Warning” colleges

As noted above, a “Warning” rating is assigned to a private college or university when its policies clearly and consistently state that it prioritizes other values over a commitment to freedom of speech. Because Warning schools are not bound by a guarantee of freedom of speech, we present the Overall Scores for these schools separately from those colleges and universities that do guarantee freedom of speech and we do not assign Warning schools a ranking. In 2021, five Warning schools were surveyed: Hillsdale College, Brigham Young University, Pepperdine University, Saint Louis University, and Baylor University. The average score for these five colleges was 55.76 (standard deviation = 6.86).

A larger percentage of students at Warning schools, compared to students at non-Warning schools, said they were comfortable expressing their views in all five contexts asked about. Students at Warning schools also were more tolerant of all four conservative speakers, more likely to think the administration made its stance on freedom of speech clear, and were more likely to think the administration would defend a speaker during a campus controversy. The percentage of students at Warning schools who said they “very” or “fairly” often self-censor (23%) was slightly higher, however, than the percentage of students at non-Warning schools who said this (21%). Students at Warning schools also were less tolerant of all four liberal speakers and less supportive of all forms of disruptive conduct than their counterparts at non-Warning schools.

Regarding topics that students found difficult to have open and honest conversations about, the top five topics at Warning schools and non-Warning schools were identical: Racial inequality, transgender issues, abortion, gun control, and the George Floyd protests. Some differences in this area between Warning and non-Warning schools, though, were evident.

First, at Warning schools, four of these five issues were selected by 50% of the students (gun control was the exception at 45%). In contrast, at non-Warning schools only racial inequality was identified as a topic difficult to discuss by more than 50% of the students. In other words, despite showing more comfort expressing views in different contexts on campus (such as the classroom and the quad), majorities of students at Warning schools found several topics difficult to discuss.

Finally, Warning schools were more ideologically heterogeneous than non-Warning schools. A roughly equal number of students identified as liberal or conservative at Baylor University, Brigham Young University, and Pepperdine University. The student bodies at Saint Louis University and Hillsdale College were majority liberal and majority conservative, respectively.

Regional differences in freedom of speech on campus

In different regions, different topics were identified by students as difficult to have an open and honest conversation about. For example, a larger percentage of students in the Northeast identified affirmative action, economic inequality, and the Israeli/Palestinian conflict as difficult topics, compared to the other regions of the country. Students in the Northeast found it easier to discuss the topics of abortion, the George Floyd protests, gun control, and transgender issues.

Regional differences in the Comfort Expressing Ideas component, however, were almost non-existent, with one exception. Only about one-third of students in the Northeast were “very” (10%) or “somewhat” (24%) comfortable “expressing an unpopular opinion to your fellow students on a social media account tied to your name,” compared to 42% of students in the Midwest (13%, 29%) and in the South (15%, 27%), and 41% of students in the West (14%, 27%).

Regarding controversial speakers, students in the Northeast were less tolerant of conservative speakers and more tolerant of liberal speakers than students in other regions. This pattern was true for all four hypothetical liberal speakers and for three of the four hypothetical conservative speakers. The only hypothetical speaker for whom there was no significant regional difference was the one saying, “the lockdown orders issued in response to the coronavirus have infringed on our personal liberties”.

Students in the Northeast also more often found disruptive conduct acceptable. Just 28% of these students said shouting down a speaker was “never” acceptable, compared to 33% in the Midwest, 34% in the South, and 38% in the West. Similarly, more than half of the students in the Northeast (52%) said blocking entry to a campus speech was “never” acceptable, compared to 57% in the Midwest, 60% in the South, and 61% in the West. Likewise, regarding whether using violence to stop a speech was ever acceptable, 73% of students in the Northeast said it never was, compared to 75% of students in the Midwest and 77% of students in the South and West.

While students in the Northeast were less tolerant of conservative speech and more tolerant of disruptive conduct, they also perceived their administration as less tolerant of controversial speech compared with students from other regions. Almost one in three Northeast students (31%) said that it was “not very likely” (23%) or “not at all likely” (8%) that their administration would defend a speaker’s rights during a campus controversy. In contrast, 27% of students in the Midwest (21%, 6%), the South (20%, 7%), and the West (20%, 7%) expressed these opinions.

These findings might be partly explained by the fact that the student bodies on campuses in the Northeast claimed to be more liberal than the student bodies on campuses from other regions. In the Northeast, almost two in three students identified as liberal (65%), while 11% identified as conservative and 11% identified as moderate. Almost one in three identified as “very liberal” (29%) while just 2% identified as “very conservative.” There were considerably higher proportions of conservative students in other regions of the country, although self-described liberals were still the predominant ideological group on campus in all four regions. In the South, 22% identified as conservative, compared to 14% who identified as moderate and 50% who identified as liberal. In the Midwest, 20% identified as conservative, 13% identified as moderate, and 55% identified as liberal. In the West, 18% identified as conservative, 14% as moderate, and 52% as liberal.

Gender and freedom of speech on campus

As previously noted, college students across the U.S. vary tremendously in their perceptions of free speech on campus, and how comfortable they are expressing their ideas on campus. Such variation is especially noteworthy when comparing students who answered as non-binary to those who did not. This year’s survey has responses from 1,318 (3.5% of the overall respondent pool) who identify as something other than male or female, and analyzing these students’ responses together reveals some interesting experiences with open inquiry for students outside of the gender binary.

In the classroom, nonbinary students were more likely than others to feel comfortable expressing dissent in all situations surveyed. Whether it’s expressing their views on a controversial topic, publicly disagreeing with a professor, or expressing disagreement with a professor about a controversial topic in a written assignment, non-binary students reported feeling more comfortable than others. For instance, when asked how comfortable they would feel publicly disagreeing with a professor on a controversial topic, almost half (49%) said they felt at least somewhat comfortable, while only 35% of female students and 45% of male students said the same. Similarly, almost half (48%) of non-binary students said they were at least somewhat comfortable expressing an unpopular opinion to their fellow students on a social media account tied to their name, with 20% saying they felt very comfortable doing so. Meanwhile, only 40% of male and female students alike said they were at least somewhat comfortable.

Males, females, and non-binary students also differed on allowing certain controversial speakers on campus. For example, only 15% of students answering as non-binary said they would at least somewhat support their school allowing a speaker who says, “Transgender people have a mental disorder.” In comparison, 36% of male students and 12% of female students would allow this speaker. Meanwhile, support for more liberal-leaning controversial speakers was higher among non-binary students than others. For example, 77% of non-binary students said they would support allowing a speaker who says, “The police should be abolished because they are racist,” with almost half (49%) of non-binary students saying they would strongly support allowing this speaker. In comparison, only 23% of male students and female students said they strongly supported allowing this speaker on campus.

With regard to disrupting a speaker on campus, non-binary students were significantly more likely to find disruption acceptable. For example, when asked if it was acceptable to shout down a speaker or try to prevent them from speaking on campus, two-thirds (65%) of non-binary students said it was acceptable, and 19% said it was always acceptable to do so. Male students, in contrast, least often said it was acceptable (27%), with 39% of female students saying so. Non-binary students also significantly more often (23%) said it was acceptable to use violence to stop a campus speech compared to their peers (7% of males and 6% of females).[13]

When asked how likely their college’s administration would defend a controversial speaker’s right to speak on campus, non-binary students twice as frequently as others said their college’s administration would be extremely likely to do so. Only 6% of male and female students said the same. Male students were more likely to say that their college protected free speech on campus compared to their female and non-binary counterparts, with 10% of males and 9% of female and nonbinary students agreeing that it is extremely clear that their college administration protects free speech on campus.[14]

College Free Speech Rankings

The data above provide meaningful perspectives into the environment for open expression on college campuses in America. But for students trying to evaluate what kind of campus climate is right for them, rankings may provide deeper insight into the tradeoffs students might choose. It is valuable for prospective students to consider what kind of college experience they want. Do they already feel comfortable speaking out about topics they are passionate about, even when they have a minority viewpoint, or do they prefer to be surrounded by students who think similarly? Do they mind if their ideas are challenged in the classroom? Are they open to hearing from different and sometimes controversial speakers, or at least to an environment where speakers are allowed to visit and speak without obstruction?

The College Free Speech Rankings, plus a more comprehensive online dashboard (speech.collegepulse.com), provide a way to compare colleges on the strength of their cultures of freedom of expression. These rankings can be used by prospective students and their parents to better understand the campus climate at colleges they may attend. Professors, administrators, and staff also can use these rankings to better understand the overall student experience on their campuses, and they can explore which topics are most uncomfortable for students to discuss openly, as well as which groups feel comfortable doing so.

What are students’ top-ranked schools for freedom of speech?

The rankings for the top 25 colleges are in the table below. (The scores of the five assessed Warning schools are provided separately, as explained above.)

Claremont McKenna College ranked first in the 2021 Campus Free Speech Rankings, with an overall score of 72.27. This score outpaced last year’s top school, the University of Chicago, by almost two points, and it was more than six points higher than the other schools in the top five.

The University of Chicago, the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), the University of Arizona, Kansas State University, Arizona State University, Duke University, the University of Virginia, and Texas A&M University all ranked in the top ten last year, and in the larger 2021 field, they all ranked highly again. All of them ranked in the top 25. The only schools previously ranked in the top ten that did not rank in the top 25 in 2021 are Brown University (ranked 52) and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech, ranked 107).

All of the top 25 schools have a Green rating from FIRE. Just over half (13) have endorsed some form of the Chicago Principles.

Table 2. Top Colleges Overall for Free Speech

Rank | Institution | Overall | Endorsed |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | Claremont McKenna College | 72.27 | Yes |

2 | University of Chicago | 70.43 | Yes |

3 | University of New Hampshire | 67.16 | No |

4 | Emory University | 67.14 | No |

5 | Florida State University | 66.95 | Yes |

6 | Purdue University | 66.57 | Yes |

7 | University of Maryland | 66.44 | Yes |

8 | University of California, Los Angeles | 66.43 | No |

9 | University of Arizona | 66.41 | Yes |

10 | College of William and Mary | 65.88 | No |

11 | University of Mississippi | 65.87 | No |

12 | George Mason University | 65.42 | Yes |

13 | Oregon State University | 65.38 | No |

14 | Kansas State University | 65.16 | Yes |

15 | Arizona State University | 65.09 | Yes |

16 | Mississippi State University | 65.06 | No |

17 | University of Colorado | 65.05 | Yes |

18 | Duke University | 65.05 | No |

19 | University of Florida | 64.82 | Yes |

20 | Auburn University | 64.55 | No |

21 | University of Tennessee | 64.52 | No |

22 | University of Virginia | 64.47 | Yes |

23 | University of North Carolina | 64.46 | Yes |

24 | North Carolina State University | 64.39 | No |

25 | Texas A&M University | 63.67 | No |

Rank | 1 |

|---|---|

Institution | Claremont McKenna College |

Overall Score | 72.27 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 2 |

Institution | University of Chicago |

Overall Score | 70.43 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 3 |

Institution | University of New Hampshire |

Overall Score | 67.16 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 4 |

Institution | Emory University |

Overall Score | 67.14 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 5 |

Institution | Florida State University |

Overall Score | 66.95 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 6 |

Institution | Purdue University |

Overall Score | 66.57 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 7 |

Institution | University of Maryland |

Overall Score | 66.44 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 8 |

Institution | University of California, Los Angeles |

Overall Score | 66.43 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 9 |

Institution | University of Arizona |

Overall Score | 66.41 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 10 |

Institution | College of William and Mary |

Overall Score | 65.88 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 11 |

Institution | University of Mississippi |

Overall Score | 65.87 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 12 |

Institution | George Mason University |

Overall Score | 65.42 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 13 |

Institution | Oregon State University |

Overall Score | 65.38 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 14 |

Institution | Kansas State University |

Overall Score | 65.16 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 15 |

Institution | Arizona State University |

Overall Score | 65.09 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 16 |

Institution | Mississippi State University |

Overall Score | 65.06 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 17 |

Institution | University of Colorado |

Overall Score | 65.05 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 18 |

Institution | Duke University |

Overall Score | 65.05 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 19 |

Institution | University of Florida |

Overall Score | 64.82 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 20 |

Institution | Auburn University |

Overall Score | 64.55 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 21 |

Institution | University of Tennessee |

Overall Score | 64.52 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 22 |

Institution | University of Virginia |

Overall Score | 64.47 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 23 |

Institution | University of North Carolina |

Overall Score | 64.46 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | Yes |

Rank | 24 |

Institution | North Carolina State University |

Overall Score | 64.39 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Rank | 25 |

Institution | Texas A&M University |

Overall Score | 63.67 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

At the other end of the rankings, DePauw University again ranked the lowest with an overall score of 50.80 this year. Marquette University, Louisiana State University (LSU), Boston College, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), Bates College, Tulane University, Utah State University, Colby College, and Fordham University round out the bottom ten institutions in 2021. LSU ranked low last year as well, while the remaining institutions were surveyed for the first time in 2021.

It also is noteworthy that RPI has been awarded a lifetime censorship award by FIRE,[15] while Marquette,[16] Boston College,[17] and Tulane[18] have long histories of speech controversies on their respective campuses. Students generally have no misconception about the poor campus environment of these institutions for free speech.

Other well-known, low-ranked schools include Middlebury College (140), Princeton University (135), Georgetown University (131), and Harvard University (130).

The full rankings table is available in Appendix 2 and the College Free Speech Rankings Dashboard (speech.collegepulse.com), which can be found on the College Pulse, FIRE, and RealClearEducation websites.

How did “Warning” colleges perform?

The overall scores of the “Warning” schools are relatively low, with one exception, compared with the other schools in the survey. The average overall score for the five Warning schools was 55.76, below the average of 59.49 at the others. Among the four schools with relatively low scores, the scores ranged from 51.18 (worse than Marquette University) to 53.78 (worse than Middlebury College). Hillsdale College, in contrast, had a relatively high score of 67.91. We profile Hillsdale in more detail below.

Table 3. Overall Scores for Warning Colleges

Institution | Overall | Endorsed |

|---|---|---|

Hillsdale College | 67.91 | No |

Brigham Young University (BYU) | 53.78 | No |

Pepperdine University | 53.22 | No |

Saint Louis University (SLU) | 52.69 | No |

Baylor University | 51.18 | No |

Institution | Hillsdale College |

|---|---|

Overall Score | 67.91 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Institution | Brigham Young University (BYU) |

Overall Score | 53.78 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Institution | Pepperdine University |

Overall Score | 53.22 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Institution | Saint Louis University (SLU) |

Overall Score | 52.69 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Institution | Baylor University |

Overall Score | 51.18 |

Endorsed Chicago Principles | No |

Not counting Hillsdale College, performance on the Openness component was below or greatly below average compared with the total sample of 159 institutions. BYU’s Openness score would have ranked 87, while Baylor University’s, Pepperdine University’s, and SLU’s Openness scores would have ranked in the bottom quartile. Similarly, on the Tolerance for Liberal Speakers component, SLU would have ranked 70 and Pepperdine would have ranked 99 (or 100 if including SLU). Baylor and BYU would have ranked near the very bottom.

Pepperdine and SLU, nevertheless, scored above average on the Comfort Expressing Ideas component, and all four scored above average on the Disruptive Conduct component. Furthermore, three of the four institutions (Baylor, BYU, and Pepperdine) performed relatively well on the Tolerance for Conservative Speakers component, with scores in the top quartile, while SLU scored poorly.

With the exception of Hillsdale College, the Warning schools do not score highly, which suggests that FIRE’s “Warning” designation should be taken seriously by prospective students. These institutions prioritize other values over a commitment to freedom of speech, and current students recognize that such priorities play out in the campus culture.

Individual School Profiles

This section analyzes five colleges in greater detail to help demonstrate the value of campus-specific data on student attitudes about free speech. These analyses capture important differences between campuses that may be obscured by analyses of national data.

Claremont McKenna College

The top-ranked college in the 2021 Campus Free Speech Rankings, Claremont McKenna College (CMC), had an overall score of 72.27. CMC eclipsed last year’s top-ranked college, the University of Chicago, by almost two full points. Among liberal arts colleges, CMC overwhelmed its closest competitor, Bowdoin College, by almost ten points. In fact, for each component of the rankings, CMC ranked in the top 50, having the top score on both Tolerance for Liberal Speakers and Tolerance for Conservative Speakers.

Over the past few years, CMC has made it clear that freedom of speech is an important value. In 2018 it became the first college in California to attain a Green rating from FIRE.[19] In 2019 CMC received Heterodox Academy’s Award for Institutional Excellence for launching the Open Academy initiative and for how the administration handled a campus speech controversy involving Heather Mac Donald.[20] CMC students clearly perceive this commitment; CMC ranked in the top ten on Administrative Support for Free Speech.

During the Mac Donald controversy, students from CMC and other Claremont Colleges blocked the entrance of the Athenaeum, where Mac Donald was scheduled to speak. Due to safety concerns, the college administration, in conjunction with the campus police department, elected to livestream her talk, which she gave to an empty auditorium. The livestream was then posted on the college’s website. The college administration investigated and ultimately suspended the students who had blocked entry to the event in an attempt to disrupt the event. CMC President Hiram Chodosh[21] and Vice President for Academic Affairs Peter Uvin[22] both came out staunchly in support of freedom of speech and condemned the actions of those who had blocked entry.

These are likely some of the reasons why a majority of CMC students (54%) said their administration makes it “extremely” (20%) or “very” (34%) clear that the administration will protect freedom of speech on campus, and why almost nine in ten students (89%) say it’s likely the administration would defend a speaker's right to speak if a controversy over offensive speech occurred. In both cases these percentages are well above the national averages. In particular, the percentage of CMC students who said that it was “extremely” clear that the administration would defend freedom of speech on campus was 20%, more than double the national figure of 9%.

A majority of CMC students supported allowing six of the eight controversial speakers, ranging from 55% (for “abortion should be completely illegal”) to 93% (for “white people are collectively responsible for structural racism and use it to protect their privilege”). The two areas where a majority of CMC students were intolerant regarded were “transgender people have a mental disorder” (two in five allowing) and “Black Lives Matter is a hate group” (just under two in five, 38%, allowing). Overall, though, CMC ranked highest on both tolerance components.

When asked which topics were difficult to have an open and honest conversation about, the percentage of CMC students who selected each topic was typically below the national figure. The three exceptions to this, where CMC students reported more difficulty than the national average, were affirmative action (37% vs. 29% nationally), economic inequality (42% vs. 33%), and the Israeli/Palestinian conflict (43% vs. 30%).

Similarly, on the Disruptive Conduct component, a greater percentage of CMC students agreed that shoutdowns (44% vs. 34% nationally) and blocking entry to a campus speech (64% vs. 59%) were “never” acceptable. Even so, a majority of CMC students found shoutdowns acceptable to some degree, and about one third found blocking entry acceptable to some degree. There was almost no difference in the percentages of CMC students and students nationally who said violence was “never” acceptable.

CMC students also tended to be more comfortable expressing themselves across a variety of contexts, compared to students nationally. The one exception was when students were asked about “expressing an unpopular opinion to your fellow students on a social media account tied to your name.” Just three in ten CMC students said they felt comfortable doing so, compared to four in ten students nationally.

There remain various areas for improvement at Claremont McKenna College. It is not just that a majority of students found shouting down a speaker acceptable to some degree; relatively strong numbers compared with other colleges should not distract from the significant proportions of CMC students who expressed intolerance, self-censorship, or negative opinions about the college’s climate for free speech.

For example, even though CMC students tended to be relatively tolerant in general, 2.7 times as many conservative vs. liberal students reported frequently self-censoring (38% vs. 14%). Also, few of CMC’s liberal students (less than one in three) either somewhat or strongly supported allowing three of the hypothetical conservative speakers to speak on campus, and just half would allow the speaker saying, “The lockdown orders issued in response to the coronavirus have infringed on our personal liberties.” These findings might not be surprising in CMC’s overwhelmingly liberal environment: 72% of students self-identified as liberal, compared to 11% as conservative and 8% as moderate.

Although many more conservative than liberal CMC students reported self-censorship, the groups reported about equal comfort expressing themselves across a variety of contexts. There was one exception: A majority of liberal students (57%) said they felt comfortable “expressing your views on a controversial political topic during an in-class discussion,” compared to 44% of conservative students. Nevertheless, these are epidemic levels of discomfort at an institution that ought to function as an open marketplace of ideas.

Marquette University

Marquette University, ranked 153 with an Overall Score of 51.61, is no stranger to controversy over freedom of speech.[23] For two years running—in 2015 and 2016 (for the years 2014 and 2015)—FIRE named Marquette one of the ten worst colleges for free speech[24] because of its attempts to revoke the tenure of Professor John McAdams and then terminate him.[25] It took more than three years, but McAdams ultimately won his lawsuit against the university and was reinstated to his faculty position in the fall of 2018.[26]

Marquette students clearly perceived their administration’s weak stance on freedom of speech. Marquette students said about 1.5 times as often as in the national sample that it was “not very likely” (27%) or “not at all likely” (16%) that their administration would defend a speaker’s right to freedom of speech during a campus controversy (totaling 43% vs. 28% nationally). Also, fewer than one in five of students said that the administration made its policy on freedom of speech “extremely” (9%) or “very” (10%) clear, compared with national percentages of 9% and 23%. Meanwhile, 16% of Marquette students said that the administration’s position was “not at all clear,” compared with 12% nationally.

Furthermore, one in four Marquette students said they self-censor “fairly” (15%) or “very” (10%) often, while just 8% said they “never” did so. Among students nationally, 17% said they “never” self-censor, more than twice the percentage of Marquette students. Self-censorship was particularly pronounced among conservative students at Marquette: 45% said they self-censored “fairly” (26%) or “very” (19%) often, but just 13% of liberal students said that they did so “fairly” (6%) or “very” (7%) often.

Frequent self-censorship among Marquette males was reported twice as often as among females. Slightly more than one in three male students (34%) said they self-censored “fairly” (20%) or “very” (14%) often. In contrast, 17% of female students said they self-censored “fairly” (10%) or “very” (7%) often.

Abortion, the George Floyd protests, and racial inequality were particulalrly difficult topics to discuss at Marquette. Almost six in ten students (56%) selected both abortion and racial inequality as difficult topics to have open and honest conversations about, and about half of students (49%) selected the George Floyd protests. Notably, a greater percentage of liberal students (64%) than conservative students (55%) selected abortion, but a greater percentage of conservatives (57%) than liberals (46%) selected George Floyd protests. A roughly equal percentage of liberals (54%) and conservatives (57%) selected racial inequality.

Gender also determined some differences in this area. A greater percentage of female students (65%) than male students (47%) selected abortion. A little over half of females (53%) selected the George Floyd protests, compared to 45% of males. But the percentages of female (58%) and male (55%) students who selected racial inequality were roughly equal.

Allowing controversial speakers to speak on campus was also unpopular among Marquette students, who displayed considerable intolerance. A majority of Marquette students were opposed to allowing six of the eight controversial speakers. The only hypothetical speakers whom a majority of students would allow were the ones saying, “White people are collectively responsible for structural racism and use it to protect their privilege” (64%) or,“Religious liberty is used as an excuse to discriminate against gays and lesbians” (54%).

Marquette scores poorly in the 2021 Campus Free Speech Rankings for a multitude of reasons. Students do not think the administration’s stance on freedom of speech is clear, and they are skeptical that a speaker’s rights would be defended if a campus controversy erupted. Marquette students also self-censor at higher rates than students nationwide and tend to oppose allowing controversial speakers on campus. In fact, the only rankings component on which Marquette does not perform poorly is Disruptive Conduct. In other words, it appears that Marquette University remains one of the worst schools for freedom of speech in the United States.

Wesleyan University

Wesleyan University ranked 29 with an Overall Score of 62.15. It is also one of the highest-ranked liberal arts colleges. President Michael Roth is an active participant in public debate over freedom of speech on campus and other higher education issues.[27] He has argued, however, for a “proactive” stance regarding “harassment,” which is a threat to free expression:

We’re not in a position where we have to wait for repetitive harassment to occur so it meets the legal definition. We can be proactive. Because when students go to college, they aren’t signing up for a marketplace, they’re signing up for a community.[28]

Nevertheless, just over two-thirds of students reported that they were comfortable “expressing disagreement with one of your professors about a controversial topic in a written assignment,” compared to 58% of students nationally. Wesleyan students were also a bit more comfortable than average “expressing your views on a controversial political topic during an in-class discussion” (56% vs. 52%). Social media, however, went the other way: a greater percentage of Wesleyan students (65%) than students in the national sample (60%) said they were uncomfortable “expressing an unpopular opinion to your fellow students on a social media account tied to your name.”

Wesleyan students also were more accepting of disruptive conduct than students nationally. More than eight in ten Wesleyan students (82%) said shouting down a speaker was acceptable to some degree, compared to 66% of students nationally. Female Wesleyan students were particularly accepting of shouting down a speaker (84%), compared to 79% of Wesleyan males.

Moreover, more than half of Wesleyan students (53%) said that blocking entry to a campus speech was acceptable to some degree. Almost two in five (39%) even said that using violence to stop a speech was acceptable to some degree. Both of these percentages were well above the national averages of 41% and 24% respectively. Many students at Wesleyan are learning the wrong lessons about tolerance.

Finally, despite President Roth’s frequent participation in public discourse about freedom of speech on campus, only one in five Wesleyan students said the administration’s stance on protecting freedom of speech on campus was “extremely” (3%) or “very” (18%) clear. Yet, three-fourths of students said that the administration would likely defend a speaker’s right to freedom of speech during a campus controversy. If students are learning the wrong lessons about free speech at Wesleyan, they might not be getting those bad lessons from the central administration but from elsewhere.

In sum, Wesleyan does fairly well in the 2021 Campus Free Speech Rankings. Students report an environment in which they can have open and honest conversations about controversial topics, they feel comfortable expressing themselves in a variety of contexts, and speakers espousing politically liberal views are welcome on campus (likely because of the ideological homogeneity at the school). Wesleyan’s score was weighed down, however, because its almost entirely liberal student body vociferously opposed even allowing conservative speakers on campus, suggesting an echo chamber with a dearth of substantially dissenting viewpoints on campus and in the classroom.

Hillsdale College

By a considerable margin, Hillsdale College was the highest-scoring “Warning” school surveyed, with an overall score of 67.91. Its score overwhelmed Brigham Young University’s at 53.78. Hillsdale would have ranked third between the University of Chicago (70.43) and the University of New Hampshire (67.16).

In fact, for all but one of the components of the Overall Score, Hillsdale scored the highest among all 159 institutions surveyed. That is, Hillsdale students generally reported a campus environment where they could have open and honest conversations about controversial topics. For instance, while 45% of students at non-Warning colleges said that gun control was a topic that was difficult for them to have an open and honest conversation about, only 15% of Hillsdale students selected this item.

When it came to Comfort Expressing Ideas in different contexts, the percentages of Hillsdale students who said they were comfortable doing so ranged from a low of 67% when “expressing an unpopular opinion to your fellow students on a social media account tied to your name” to a high of 93% when “expressing your views on a controversial political topic to other students during a discussion in a common campus space (e.g., quad, dining hall, or lounge).” All of these percentages dwarf the average percentages at non-Warning schools, which range from a low of 39% (social media) to a high of 60% (a common campus space).

An overwhelming majority of Hillsdale students considered disruptive conduct, whether shouting down speakers (60%), blocking entry to campus events (86%), or using violence to stop a speech (90%), “never” acceptable. At the national level these percentages were only 34%, 59%, and 76% respectively, while at other Warning schools they were 43%, 64%, and 78% respectively.

Finally, over eight in ten (85%) Hillsdale students said that the administration makes it “clear” that Hillsdale protects freedom of speech on campus. In comparison, at Claremont McKenna, the top-ranked college overall and one whose administration has been quite clear about its own stance on freedom of speech, just 54% of students said their administration’s stance was clear. At the University of Chicago, this figure was 45%. Furthermore, when Hillsdale students were asked if they expected the administration to defend a speaker’s right to freedom of speech in the face of controversy, a near-unanimous proportion of students, 98%, reported that it was “likely” the administration would do so.

Thus, it is clear that despite Hillsdale’s rating of Warning, the vast majority of Hillsdale students report a campus environment that strongly supports freedom of speech.

But the survey suggests that those in the ideological minority at Hillsdale, liberal students, often do not experience the campus environment in this way. The student body at Hillsdale was the most conservative in the survey by a great margin, with 77% of students identifying as conservative. The next closest proportion was at Utah State University with a 49% conservative minority. In other words, Hillsdale was the only college surveyed where more than half of the students identified as conservative.

Accordingly, it might not be surprising that liberal students did not report an open environment. Of the 15 topics surveyed, 13 were identified by a majority of liberal students as difficult to have an open and honest conversation about. For some issues, the percentages were staggering. For instance, 93% of liberals said it was difficult to discuss racial inequality, compared to 50% of moderates and 24% of conservatives.

When it came to comfort expressing one’s ideas in various contexts, a majority of liberal students expressed comfort, but not as frequently as their conservative counterparts. For instance, just over half of liberal students (53%) were comfortable expressing their views on a controversial political topic in class, compared to 84% of conservative students. While a notably high proportion of liberals reported feeling comfortable expressing their views elsewhere, such as in a common campus space (two-thirds), the percentage of conservative students who reported the same feeling was considerably larger (97%).

Similarly, Hillsdale students were overwhelmingly in favor of allowing controversial conservative speakers but not liberal speakers on campus. In fact, Hillsdale was one of only five colleges surveyed (BYU, Mississippi State University, Utah State University, and the University of Wyoming being the others) where students were more tolerant of controversial conservative speakers than controversial liberal ones. At Hillsdale, support for allowing the hypothetical conservative speakers ranged from a low of 63% (“transgender people have a mental disorder”) to a high of 90% (“the lockdown orders issued in response to the coronavirus have infringed on our personal liberties”). The remaining proportions of intolerant students, nevertheless, remain an educational opportunity among conservative Hillsdale students.