Table of Contents

Spotlight on Speech Codes 2020

Major Findings

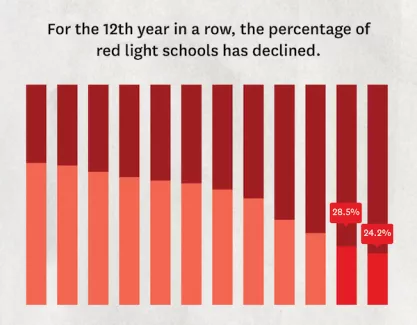

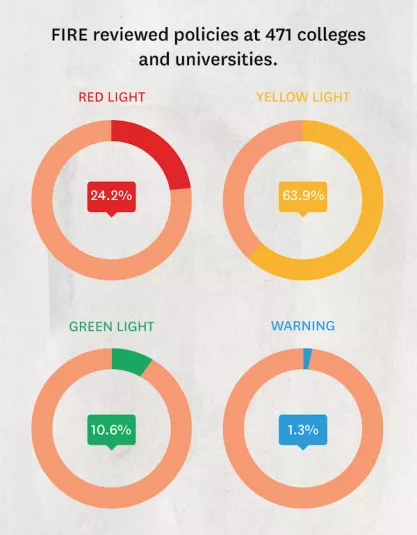

- The percentage of schools earning an overall “red light” rating in FIRE’s Spotlight database has gone down for the twelfth year in a row, this year to 24.2%. This is over a four percentage point drop from last year, and is exactly 50 percentage points lower than the percentage of red light institutions in FIRE’s 2009 report.

- The percentage of private universities earning a red light rating, which stood at 47.1% last year, continued to decrease, coming in at 44.8% this year.

- 63.9% of institutions now earn an overall “yellow light” rating. Though less restrictive than red light policies, yellow light policies restrict expression that is protected under First Amendment standards and invite administrative abuse.

- This is the first year since FIRE began rating speech codes that the list of “green light” institutions reached a total of 50 schools. (Since this year’s report was written, two more universities have earned green light status, bringing the total to 52.) Policies earn a green light rating when they do not seriously threaten protected expression. Only eight institutions earned a green light rating in FIRE’s 2009 report.

- 8.3% of institutions surveyed maintain “free speech zone” policies, which limit student demonstrations and other expressive activities to small and/or out-of-the-way areas on campus. A 2013 FIRE survey of these institutions found roughly double that percentage.

- Sixty-eight university administrations or faculty bodies have now adopted policy statements in support of free speech modeled after the “Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression” at the University of Chicago (the “Chicago Statement”), released in January 2015. (Since this year’s report was written, two more institutions have adopted a version of the Chicago Statement, bringing the total to 70.)

Executive Summary

Most college students in the United States should be able to expect that freedom of expression will be upheld on their campuses. After all, public institutions are legally bound by the First Amendment, and the vast majority of private colleges and universities promise their students commensurate free speech rights.

In spite of this legal landscape, far too many colleges across the country fail to live up to their free speech obligations in policy and in practice. Often, this occurs through the implementation of speech codes: university policies that restrict expression protected by the First Amendment.

For this report, FIRE surveyed the written policies of 471 colleges and universities, evaluating their compliance with First Amendment standards. Overall, 24.2% of surveyed colleges maintained at least one severely restrictive policy that earned FIRE’s worst, “red light” rating, meaning that it both clearly and substantially restricts protected speech. This is the twelfth year in a row that the percentage of schools earning a red light rating has gone down; last year, 28.5% of schools earned a red light rating.

The majority of institutions surveyed (63.9%) earned an overall “yellow light” rating, meaning they maintained at least one yellow light policy. Yellow light policies are either clear restrictions on a narrower adopted by the University of Chicago in January 2015. As of this writing, sixty-eight schools or faculty bodies have endorsed a version of the “Chicago Statement,” with nine adoptions in 2019 alone.

Though these improvements in policy are heartening, free speech on campus remains under threat. Demands for censorship of student and faculty speech—whether originating on or off campus—are common, and universities continue to investigate and punish students and faculty over protected expression.

Methodology

For this report, FIRE surveyed publicly available policies at 366 four-year public institutions and 105 of the nation’s most prestigious private institutions. Our research focuses in particular on public universities because, as explained in detail below, public universities are legally bound to protect students’ right to free speech and can be successfully sued in court when they do not.

FIRE rates colleges and universities as “red light,” “yellow light,” or “green light” institutions based on how much, if any, protected expression their written policies governing student conduct restrict. The speech code ratings do not take into account a university’s “as-applied” violations of student speech rights or other cases of censorship, student- or faculty-led calls for punishment of protected speech, and related incidents. Monitoring and rating such incidents consistently across 471 institutions with accuracy is not feasible and is beyond the scope of this report.

The speech code ratings are defined as follows:

Red Light: A red light institution maintains at least one policy both clearly and substantially restricting freedom of speech, or that bars public access to its speech-related policies by requiring a university login and password for access.

A “clear” restriction unambiguously infringes on protected expression. In other words, the threat to free speech at a red light institution is obvious on the face of the policy and does not depend on how the policy is applied. A “substantial” restriction on free speech is one that is broadly applicable to campus expression. For example, a ban on “offensive speech” would be a clear violation (in that it is unambiguous) as well as a substantial violation (in that it covers a great deal of what is protected under First Amendment standards). Such a policy would earn a university a red light.

When a university restricts access to its speech-related policies by requiring a login and password, it denies prospective students and their parents the ability to weigh this crucial information prior to matriculation. At FIRE, we consider this denial to be so deceptive and serious that it alone warrants an overall red light rating.

Yellow Light: A yellow light institution maintains policies that could be interpreted to suppress protected speech or policies that, while clearly restricting freedom of speech, restrict relatively narrow categories of speech.

For example, a policy banning “verbal abuse” has broad applicability and poses a substantial threat to free speech, but it is not a clear violation because “abuse” might refer to unprotected speech and conduct, such as threats of violence or unlawful harassment. Similarly, while a policy banning “profanity on residence hall door whiteboards” clearly restricts speech, it is relatively limited in scope. Yellow light policies are typically unconstitutional,[1] and a rating of yellow light rather than red light in no way means that FIRE condones a university’s restrictions on speech. Rather, it means that in FIRE’s judgment, those restrictions do not clearly and substantially restrict speech in the manner necessary to warrant a red light rating.

Green Light: If FIRE finds that a university’s policies do not seriously threaten campus expression, that college or university receives a green light rating. A green light rating does not necessarily indicate that a school actively supports free expression in practice; it simply means that the school’s written policies do not pose a serious threat to free speech.

Warning: FIRE believes that free speech is not only a moral imperative, but an essential element of a college education. However, private universities, as private associations, possess their own right to free association, which allows them to prioritize other values above the right to free speech if they wish to do so. Therefore, when a private university clearly and consistently states that it holds a certain set of values above a commitment to freedom of speech, FIRE warns prospective students and faculty members of this fact.[2] Six schools surveyed for this report meet these criteria.[3]

Findings

Of the 471 schools reviewed by FIRE, 114, or 24.2%, received a red light rating. 301 schools received a yellow light rating (63.9%), and fifty received a green light rating (10.6%). Six schools earned a Warning rating (1.3%).[4]

This marks the twelfth year in a row that the percentage of universities with an overall red light rating has fallen, this year from 28.5% to 24.2%. The continued reduction in red light institutions is encouraging: In the eleven years since the release of our 2009 report, red light schools have declined by exactly fifty percentage points.[5] This is a dramatic shift to have taken place in just over a decade.

However, this year’s numbers also reveal an increase in yellow light institutions, as 61.2% of schools earned an overall yellow light last year, compared to 63.9% this year. While yellow light policies are not as clearly and substantially restrictive as red light policies on their face, they nevertheless impose impermissible restrictions on expression, as discussed in further detail in this report’s “Spotlight On: Yellow Light Policies” feature.

The number of green light institutions has continued to increase this year, going from forty-two institutions last year to fifty.[6] Significantly, this was the first year since FIRE began rating speech codes that the list of green light institutions reached a total of fifty schools. At 10.6%, this was also the first year that green light schools comprised over 10% of the database. Now, more than one million students across the country are enrolled at green light colleges and universities.[7]

While eleven schools in total were added to our list of green light institutions this year, three schools were, unfortunately, removed from the list.[8] In total, thirty-five schools improved their overall ratings this year.[9]

Public Colleges and Universities

The percentage of public schools with a red light rating dropped again, from 23.2% last year to 18.3% this year. Overall, of the 366 public universities reviewed for this report, sixty-seven received a red light rating (18.3%), 252 received a yellow light rating (68.9%), and forty-seven received a green light rating (12.8%).

This year, FIRE was pleased to welcome Northern Arizona University and the University of Arizona to the list of green light institutions. Since Arizona State University has earned an overall green light rating since 2011, all of the four-year public universities in Arizona now earn FIRE’s highest rating, making Arizona the only state able to claim this distinction.

In another state-wide success story, Alcorn State University, Delta State University, and the University of Southern Mississippi all earned green light ratings this year, joining the University of Mississippi and Mississippi State University on the green light list.

The successes in these states demonstrate that revisions at one school can inspire change across statewide systems. In the coming year, FIRE will continue to work strategically to reform policies at public university systems across the country.

Private Colleges and Universities

Of the 105 private colleges and universities reviewed, forty-seven (44.8%) received a red light rating. Forty-nine (46.7%) received a yellow light rating, three (2.9%) received a green light rating, and six (5.7%) earned a Warning rating.

The percentage of private universities earning a red light rating, which stood at 47.1% last year, continued to decrease, coming in at 44.8% this year. This progress is hard-earned, given that private universities are not legally bound by the First Amendment, which regulates only government actors. For this reason, it is gratifying that these colleges are closer to fulfilling their institutional commitments to free expression.

Unfortunately, three private universities that previously earned green light ratings, Carnegie Mellon University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Emory University, all lost their place on the green light list this year.

Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pennsylvania had been long-standing green light institutions, first joining the green light list over ten years ago. After discovering policies that earned yellow light ratings and, thus, threatened these institutions’ green light statuses, FIRE reached out to alert the universities to the problem. Unfortunately, neither of the schools revised the policies in question. As a result, they both now earn yellow light ratings.

Emory University lost its green light rating in a different way: by password protecting the policy portal on its website. As mentioned earlier, when a school prevents prospective students and other interested members of the public from viewing its speech-related policies, it is awarded an automatic red light rating for restricting this crucial information.

Discussion

SPEECH CODES ON CAMPUS: BACKGROUND AND LEGAL CHALLENGES

Speech codes—university regulations prohibiting expression that would be constitutionally protected in society at large—gained popularity with college administrators in the 1980s and 1990s. As discriminatory barriers to education declined, female and minority enrollment increased. Concerned that these changes would cause tension and that students who finally had full educational access would arrive at institutions only to be offended by other students, college administrators enacted speech codes.

In the mid-1990s, the phenomenon of campus speech codes converged with the expansion of Title IX, the federal law prohibiting sex discrimination in educational institutions receiving federal funds.[10] Under the guise of the obligation to prohibit discriminatory harassment, unconstitutionally overbroad harassment policies banning subjectively offensive conduct proliferated.

In enacting speech codes, administrators ignored or did not fully consider the philosophical, social, and legal ramifications of placing restrictions on speech, particularly at public universities. As a result, federal courts have overturned speech codes at numerous colleges and universities over the past three decades.[11]

Despite the overwhelming weight of legal authority against speech codes, a large number of institutions—including some of those that have been successfully sued on First Amendment grounds—still maintain unconstitutional and illiberal speech codes. It is with this unfortunate fact in mind that we turn to a more detailed discussion of the ways in which campus speech codes violate individual rights and what can be done to challenge them.

PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES VS. PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES

With limited, narrowly defined exceptions, the First Amendment prohibits the government—including governmental entities such as state universities—from restricting freedom of speech. A good rule of thumb is that if a state law would be declared unconstitutional for violating the First Amendment, a similar regulation at a state college or university is likewise unconstitutional.

The guarantees of the First Amendment generally do not apply to students at private colleges because the First Amendment regulates only government conduct.[12] Moreover, although acceptance of federal funding does confer some obligations upon private colleges (such as compliance with federal anti-discrimination laws), compliance with the First Amendment is not one of them.

This does not mean, however, that students and faculty at all private schools are not entitled to free expression. In fact, most private universities explicitly promise freedom of speech and academic freedom in their official policy materials. Colby College, for example, states in its student handbook that the right of free expression “is essential in an academic community and will be vigorously upheld.”[13] Similarly, Furman University’s student handbook provides: “Students are guaranteed freedom of inquiry and expression,” as well as the “right of peaceable assembly.”[14] Yet both of these institutions, along with most other private colleges and universities, maintain policies that prohibit the very speech they promise to protect.[15]

This year, both private and public institutions, including statewide systems, have continued to adopt policy statements in support of free speech modeled after the one produced in January 2015 by the Committee on Freedom of Expression at the University of Chicago.[16] Since our last report, nine more institutions have adopted policy statements in support of free speech modeled after the Chicago Statement. Notably, three of those adoptions were by university systems that govern multiple colleges and universities across a particular state: the Nevada System of Higher Education, the State University System of Florida, and the Board of Regents of the State of Iowa.

Thanks to the affirmative commitment to freedom of expression by these higher education systems, an additional 500,000 students can now claim their institution promises to actively prioritize and defend free speech on campus.

WHAT EXACTLY IS “FREE SPEECH,” AND HOW DO UNIVERSITIES CURTAIL IT?

What does FIRE mean when we say that a university restricts “free speech”? Do people have the right to say absolutely anything, or are certain types of expression unprotected?

Simply put, the overwhelming majority of speech is protected by the First Amendment. Over the years, the Supreme Court has carved out a limited number of narrow exceptions to the First Amendment, including speech that incites reasonable people to immediate violence; so-called “fighting words” (face-to-face confrontations that lead to physical altercations); harassment; true threats and intimidation; obscenity; and defamation. If the speech in question does not fall within one of these exceptions, it most likely is protected.

The exceptions are often misapplied and abused by universities to punish constitutionally protected speech. There are instances where the written policy at issue may be constitutional—for example, a prohibition on “incitement”—but its application may not be. In other instances, a written policy will purport to be a legitimate ban on a category of unprotected speech like harassment or true threats, but (either deliberately or through poor drafting) will encompass protected speech as well. Therefore, it is important to understand what these narrow exceptions to free speech actually mean in order to recognize when they are being misapplied.

Threats and Intimidation

The Supreme Court has defined “true threats” as “statements where the speaker means to communicate a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence to a particular individual or group of individuals.” Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343, 359 (2003). The Court also has defined “intimidation,” of the type not protected by the First Amendment, as a “type of true threat, where a speaker directs a threat to a person or group of persons with the intent of placing the victim in fear of bodily harm or death.” Id. at 360. Neither term would encompass, for example, a vaguely worded statement that is not directed at anyone in particular.

Nevertheless, universities frequently misapply policies prohibiting threats and intimidation so as to infringe on protected speech, citing generalized concerns about safety with no regard to the boundaries of protected speech. Too many institutions also fail to meet the legal standards for these First Amendment exceptions in written policies.

For example:

- North Dakota State University bans “[i]ntimidation,” defined as conduct in any form “that involves an expressed or implied threat to an individual’s personal safety, safety of property, academic efforts, employment, or participation in University sponsored activities,” without further defining “threat” or requiring that the speech be directed with the intent of placing the victim in fear of bodily harm.[17]

- The University of Wisconsin – Green Bay states that no person may make threats of violence and that this includes “[a]cts or threats made directly or indirectly by words, gestures or symbols.”[18]

- The University of Missouri System bans threatening or intimidating behaviors, defined as “written or verbal conduct that causes a reasonable expectation of injury to the health or safety of any person or damage to any property or implied threats or acts that cause a reasonable fear of harm in another.”[19]

Universities must revise such policies so that they track the applicable legal standards and must enforce the policies accordingly.

Incitement

There is also a propensity among universities to restrict speech that offends other students on the basis that it constitutes “incitement.” The basic concept, as administrators too often see it, is that offensive or provocative speech will anger those who disagree with it, perhaps so much so that it moves them to violence. While preventing violence is necessary, this is an impermissible misapplication of the incitement doctrine.

Incitement, in the legal sense, does not refer to speech that may lead to violence on the part of those opposed to or angered by it, but rather to speech that will lead those who agree with it to commit immediate violence. In other words, the danger is that certain speech will convince sympathetic, willing listeners to take immediate unlawful action.

The paradigmatic example of incitement is a person standing on the steps of a courthouse in front of a torch-wielding mob and urging that mob to burn down the courthouse immediately. Misapplying the doctrine to encompass an opposing party’s reaction to speech they dislike converts the doctrine into an impermissible “heckler’s veto,” where violence threatened by those angry about particular speech is used as a reason to censor that speech. As the Supreme Court has observed, speech cannot be prohibited because it “might offend a hostile mob” or because it may prove “unpopular with bottle throwers.”[20]

The legal standard for incitement was announced in the Supreme Court’s decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969). There, the Court held that the state may not “forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Id. at 447 (emphasis in original). This is an exacting standard, as evidenced by its application in subsequent cases.

For instance, in Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105 (1973), the Supreme Court held that a man who had loudly stated: “We’ll take the fucking street later” during an anti-war demonstration did not intend to incite or produce immediate lawless action. The Court found that “at worst, it amounted to nothing more than advocacy of illegal action at some indefinite future time,” and that the man could therefore not be convicted under a state disorderly conduct statute. Id. at 108–09. The fact that the Court ruled in favor of the speaker despite the use of such strong and unequivocal language underscores the narrow construction that has traditionally been given to the incitement doctrine, and its dual requirements of likelihood and immediacy. Nonetheless, college administrations have been all too willing to abuse or ignore this jurisprudence.

Obscenity

The Supreme Court has held that obscene expression, to fall outside of the protection of the First Amendment, must “depict or describe sexual conduct” and must be “limited to works which, taken as a whole, appeal to the prurient interest in sex, which portray sexual conduct in a patently offensive way, and which, taken as a whole, do not have serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15, 24 (1973).

This is a narrow definition applicable only to some highly graphic sexual material. It does not encompass profanity, even though profane words are often colloquially referred to as “obscenities.” In fact, the Supreme Court has explicitly held that profanity is constitutionally protected. In Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971), the defendant, Paul Robert Cohen, was convicted in California for wearing a jacket bearing the words “Fuck the Draft” in a courthouse. The Supreme Court overturned Cohen’s conviction, holding that the message on his jacket, however vulgar, was protected speech.

Similarly, in Papish v. Board of Curators of the University of Missouri, 410 U.S. 667 (1973), the Court determined that a student’s expulsion for distributing a student newspaper containing an article titled “Motherfucker Acquitted” violated the First Amendment. The Court wrote that “the mere dissemination of ideas—no matter how offensive to good taste—on a state university campus may not be shut off in the name alone of ‘conventions of decency.’” Id. at 670.

Nonetheless, many colleges erroneously believe that they may lawfully prohibit profanity and vulgar expression. For example:

- Kean University prohibits the placement of information that is “profane or sexually offensive to the average person” on its computer resources.[21]

- The University of Texas at San Antonio’s posting policy states that materials to be posted on campus may not contain material that is “vulgar.”[22]

- Murray State University bans the use of information technology resources in an “offensive, profane, or abusive manner,” and explains that the perception of the affected person is a “major factor” in determining if an action is in violation of the policy.[23]

Harassment

Hostile environment harassment, properly defined, is not protected by the First Amendment. In the educational context, the Supreme Court has defined student-on-student harassment as discriminatory, unwelcome conduct that is “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively bars the victim’s access to an educational opportunity or benefit.” Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, 526 U.S. 629, 633 (1999).

This is not simply expression; it is conduct far beyond the protected speech that is too often deemed “harassment” on today’s college campus. Harassment is extreme and usually repetitive behavior—behavior so serious that it would interfere with a reasonable person’s ability to receive his or her education. For example, in Davis, the conduct found by the Court to be harassment was a months-long pattern of conduct including repeated attempts to touch the victim’s breasts and genitals, together with repeated sexually explicit comments directed at and about the victim.

For decades now, however, many colleges and universities have maintained policies defining harassment too broadly and prohibiting constitutionally protected speech. And years of Title IX enforcement by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) that neglected to fully protect First Amendment rights, including an unconstitutionally broad definition of sexual harassment promulgated by OCR,[24] led numerous colleges and universities to enact overly restrictive harassment policies in an effort to avoid an OCR investigation. It will likely take a great deal of time and effort by free speech advocates to undo this damage.

Here are just a few examples of overly broad sexual harassment policies based on OCR’s definition:

- Southern Utah University directly quotes OCR’s April 2011 “Dear Colleague” guidance letter[25] in defining sexual harassment as “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature,” and encourages students to report such incidents to the administration.[26]

- Colgate University’s policy defines harassment as “unwelcome, offensive conduct” that occurs on the basis of certain listed characteristics, and states that harassing conduct can occur through “graphic comments,” “jokes or comments that demean a person,” and creating “racially, ethnically, religiously offensive” cartoons.[27]

- Alabama A&M University defines sexual harassment as “any and all unwelcomed sexual advances between members of the same and/or opposite sex,” and defines sexual advances as including “[v]erbal comments of a suggestive nature” and “[v]isual or written materials that include content that is sexual in nature.”[28]

These examples, along with many others, demonstrate that colleges and universities often fail to limit themselves to the narrow definition of harassment that is outside the realm of constitutional protection. Instead, they expand the term to prohibit broad categories of speech that do not even approach actionable harassment, despite similar policies having been struck down by federal courts years earlier.[29]

Having discussed the most common ways in which universities misuse the narrow exceptions to the First Amendment to prohibit protected expression, we now turn to the innumerable other types of university regulations that restrict free speech on their face. Such restrictions are generally found in several distinct types of policies.

Anti-Bullying Policies

Over the past decade, FIRE has found that an increasing number of colleges and universities have adopted policies on “bullying” and “cyberbullying.” On October 26, 2010, OCR issued a letter on the topic of bullying, reminding educational institutions that they must address actionable harassment, but also acknowledging that “[s]ome conduct alleged to be harassment may implicate the First Amendment rights to free speech or expression.”[30] For such situations, OCR’s letter refers readers back to the 2003 “Dear Colleague” letter stating that harassment is conduct that goes far beyond merely offensive speech and expression. However, because it is primarily focused on bullying in the K–12 setting, the 2010 letter also urges an in loco parentis[31] approach that is inappropriate in the college setting, where students are overwhelmingly adults.[32]

Court decisions and other guidance regarding K–12 speech often “trickle up” to the collegiate setting, and indeed, FIRE has come across numerous university policies prohibiting bullying in a problematic manner. For example:

- Cheyney University of Pennsylvania warns students that they can be held accountable for posting and sending “inappropriate” and “uncivil” content online, and that “[a]ny act that is unbecoming of a CU student to include cyber bullying . . . is considered a violation of the Student Code of Conduct and the CU Student Handbook.”[33]

- At Ball State University, bullying is said to include “creating web pages,” “posting photos on social networking sites,” and “spreading rumors.”[34]

- Gettysburg College defines bullying as “unwelcome or unreasonable behavior that demeans, offends, or humiliates people either as individuals or as a group,” and states that “[a]lthough bullying may not rise to the level of harassment,” these behaviors are “inappropriate and inconsistent” with the college’s mission.[35]

But as courts have held in rulings spanning decades, speech cannot be prohibited simply because someone else finds it offensive, even deeply so.[36] Offensive speech, if it does not rise to the level of harassment or one of the other narrow categories of unprotected speech and conduct, is entitled to constitutional protection (and, accordingly, to protection at private institutions that claim to uphold the right to free speech).

Policies on Tolerance, Respect, and Civility

Many schools invoke laudable goals like respect and civility to justify policies that violate students’ free speech rights. While a university has every right to promote a tolerant and respectful atmosphere on campus, a university that claims to respect free speech must not limit discourse to only the inoffensive and respectful. And although pleas for civility and respect are often initially framed as requests, many schools have speech codes that effectively turn those requests into requirements.

For example:

- Utah State University’s conduct code states: “All interactions with faculty members, staff members, and other students shall be conducted with courtesy, civility, decency, and a concern for personal dignity.”[37]

- At Sonoma State University, students are expected to “[c]ommunicate with each other in a civil manner,” and are directed to “report to University staff any incidents of intolerance, hatred, injustice, or incivility.”[38]

- The University of Pittsburgh states that, by choosing to join the university community, students have made a “commitment to civility” and accept the obligation to behave in ways that contribute to a “civil campus environment.”[39]

While respect and civility may seem uncontroversial, most uncivil or disrespectful speech is protected by the First Amendment,[40] and is indeed sometimes of great political and social significance. Some of the expression employed in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, for example, would violate campus civility codes today. Colleges and universities may encourage civility, but public universities—and those private universities that purport to respect students’ fundamental free speech rights—may not require it or threaten mere incivility with disciplinary action.

Internet Usage Policies

University policies regulating online expression, while perhaps appearing to be narrow, can have a significant impact on students’ and faculty members’ free speech rights, given the prevalence of online communication on today’s college campuses.

Examples of impermissibly restrictive Internet usage policies include the following:

- At Fordham University, the use of information technology resources to “insult” or “embarrass” others is prohibited.[41]

- The University of Alaska Anchorage bans the transmission or posting of statements that are “bigoted, hateful or racially offensive.”[42]

- Northeastern University prohibits the transmission of material that is “annoying” in “the sole judgment of the University.”[43]

Just as speech that occurs in the public square may not be sanctioned merely because it has been found to be subjectively “offensive” or “annoying,” online speech may not be restricted on those bases alone.

Policies on Bias and Hate Speech

In recent years, colleges and universities around the country have instituted policies and procedures specifically aimed at eliminating “bias” and “hate speech” on campus.[44] These sets of policies and procedures, frequently termed “Bias Reporting Protocols” or “Bias Incident Protocols,” often include bans on protected expression. For example:

- Dickinson College defines a “bias incident” as “a pejorative act or expression” that a reasonable person would conclude is directed at a member or group based on a listed personal characteristic, and specifies that the campus police or local police department will investigate bias incidents.[45]

- Davidson College’s policy states: “Halloween parties that encourage people to wear costumes and act out in ways that reinforce stereotypes create a campus climate that is hostile to racial and ethnic minority groups,” and encourages students to report such “bias incidents.”[46]

- Mount Holyoke College provides that the potential outcomes for reported bias incidents range from a “mandatory educational project” to “required withdrawal.”[47]

While speech or expression that is based on a speaker’s prejudice may be subjectively offensive, it is nonetheless protected unless it rises to the level of harassment, true threats, or another form of unprotected speech.

Bias incident protocols often also infringe on students’ right to due process, allowing for anonymous reporting that denies students the right to confront their accusers. Moreover, universities are often heavily invested in these bias incident policies, having set up extensive regulatory frameworks and response protocols devoted solely to addressing them.

While many bias incident protocols do not include a separate enforcement mechanism, the mere threat of a bias investigation will likely be sufficient to chill speech on controversial issues. Indeed, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit recently held that, even though it lacked the power to punish students independently, the University of Michigan’s former “Bias Response Team” policy was likely to chill the speech of students because “the invitation from the Response Team to meet could carry an implicit threat of consequence should a student decline the invitation.”[48]

One recent example of speech investigated for perceived bias comes from Wake Forest University. In March 2019, a screenshot of an Instagram post that listed mock class president campaign statements, including one that said the candidate for class president wanted to “build a wall” between Wake Forest and Winston-Salem State University, went viral on social media over concerns that the post was racist, given that Winston-Salem State is a historically black institution.[49] Wake Forest’s university president thanked students for reporting the post to the university’s Bias Response Team, and promised an investigation, calling the post “deeply offensive and unacceptable.”[50]

FIRE wrote to the president to explain that the actions were chilling, and that the investigation must be dropped:

Although the university has not yet identified and formally punished anyone responsible for the image, the chilling effect precedes the imposition of final, formal discipline, and instead arises from the initiation, announcement, and maintenance of an investigation into speech WFU already knows to be protected. Official “inquiry alone trenches upon” freedom of expression. Paton v. La Prade, 469 F. Supp. 773, 778 (D.N.J. 1978) (student’s speech impermissibly chilled when anonymous request for information from a political organization resulted in being labeled a “subversive” and formally investigated).

[. . .]

The chilling effects emanating from WFU’s response may already be observable; the Instagram account referenced in the screenshots of the post has already been deleted. While WFU is not bound by the First Amendment, it has bound itself to freedom of speech, freedom of inquiry, and freedom of expression. WFU should recognize that maintaining an investigation into a post it recognizes as parody will undermine its purported goals.[51]

Indeed, when the only conduct at issue is speech that is protected under the First Amendment, even investigation as a bias incident is inappropriate.

Policies Governing Speakers, Demonstrations, and Rallies

Universities have a right to enact reasonable, narrowly tailored “time, place, and manner” restrictions that prevent demonstrations and other expressive activities from unduly interfering with the educational process.[52] They may not, however, regulate speakers and demonstrations on the basis of content or viewpoint, nor may they maintain regulations that burden substantially more speech than is necessary to maintain an environment conducive to education. Such regulations can take several forms, as discussed in the sections below.

Security Fee Policies

In recent years, FIRE has seen a number of colleges and universities hamper—whether intentionally or just through a misunderstanding of the law—the invitation of controversial campus speakers by levying additional security costs on the sponsoring student organizations.

The Supreme Court addressed a very similar issue in Forsyth County v. Nationalist Movement, where it struck down an ordinance in Georgia that permitted the local government to set varying fees for events based upon how much police protection the event would need.[53] Invalidating the ordinance, the Court wrote that “[t]he fee assessed will depend on the administrator’s measure of the amount of hostility likely to be created by the speech based on its content. Those wishing to express views unpopular with bottle throwers, for example, may have to pay more for their permit.”[54] Id. at 134. Deciding that such a determination required county administrators to “examine the content of the message that is conveyed,” the Court wrote that “[l]isteners’ reaction to speech is not a content-neutral basis for regulation. . . . Speech cannot be financially burdened, any more than it can be punished or banned, simply because it might offend a hostile mob.” Id. at 134–35 (emphasis added).

Despite this precedent, the impermissible use of security fees to burden controversial speech is all too common on university campuses:

- “Special arrangements” for security may be required if the University of Rhode Island determines an invited speaker is a “highly controversial person.”[55]

- The University of Miami vaguely states that it may require additional security to be present based on the “nature of the presentation.”[56]

- The University of Delaware shifts the responsibility for “ensuring the safety of the speaker as well as those who listen” fully onto the student organization holding the event, and provides that the costs of security “must be absorbed” by the organization.[57]

Prior Restraints

The Supreme Court has held that “[i]t is offensive—not only to the values protected by the First Amendment, but to the very notion of a free society—that in the context of everyday public discourse a citizen must first inform the government of her desire to speak to her neighbors and then obtain a permit to do so.” Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of NY, Inc. v. Village of Stratton, 536 U.S. 150, 165–66 (2002). Yet many colleges and universities enforce prior restraints, requiring students and student organizations to register their expressive activities well in advance and, often, to obtain administrative approval for those activities. For example:

- At the University of Southern California, students wishing to stage a demonstration must complete a permit application “at least two weeks” in advance.[58]

- Students at the University of Northern Colorado must apply for a permit ten business days before any outdoor event.[59]

- Wichita State University requires notification no later than 72 hours prior to any expressive activities, including everything from the mere “distribution of information leaflets” and “meetings to display group feelings or sentiments” to actual “mass protests.”[60]

Free Speech Zone Policies

Of the 471 schools surveyed for this report, thirty-nine institutions (8.3%) enforce “free speech zone” policies—policies limiting student demonstrations and other expressive activities to small and often out-of-the-way areas on campus.[61] This number represents a significant improvement over the course of the past decade: a 2013 FIRE survey of the institutions covered in this report found that 16.4%—roughly double the percentage today—maintained such policies.[62] This positive shift can be traced in large part to FIRE’s litigation and legislative efforts.

Over the past several years, free speech zones have repeatedly been struck down by courts or voluntarily revised by colleges as part of settlements to lawsuits brought by students. FIRE’s Stand Up For Speech Litigation Project has mounted successful challenges to free speech zone policies at eight colleges.[63] Most recently, the Los Angeles Community College District agreed to settle a lawsuit brought after an administrator told a student his rights were restricted to a tiny free speech zone on the Los Angeles Pierce College campus. As the largest community college district in the country, this victory for the Stand Up For Speech Litigation Project restored free speech rights to roughly 150,000 students.[64]

Additionally, state legislatures have continued to take action this year to prohibit public colleges and universities from maintaining free speech zones. Currently, seventeen states have enacted laws prohibiting these restrictive policies: Virginia, Missouri, Arizona, Kentucky, Colorado, Utah, North Carolina, Tennessee, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Arkansas, South Dakota, Iowa, Alabama, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Using language from the Campus Free Expression Act model legislation from FIRE,[65] Texas’ bill, which was signed into law in June 2019, recognizes that “all persons may assemble peaceably on the campuses of institutions of higher education for expressive activities, including to listen to or observe the expressive activities of others.”[66] Importantly, the statute declares that the “common outdoor areas of the institution’s campus are deemed traditional public forums.” In practice, this provision means that rather than being relegated to free speech zones, individuals may use any common outdoor areas for expressive activities, so long as their conduct is not unlawful and does not materially and substantially disrupt the functioning of the institution.

The Texas law also mandates that institutions inform new students of the policies during their freshman or transfer orientation, and that they develop materials, programs, and procedures to ensure that the employees that are responsible for educating or disciplining students understand the requirements of the law.[67]

Due to FIRE’s efforts in litigation and legislation, as well as our continued policy reform work, free speech zones have declined dramatically over the past decade. In spite of this progress, too many universities still maintain free speech zones. And despite being inconsistent with the First Amendment, free speech zones are more common at public universities than at private universities: 9.6% of public universities surveyed maintain free speech zones, while just 3.8% of private universities that promise their students free speech rights do.

Examples of current free speech zone policies include the following:

- At Tulane University, all demonstrations must be registered at least two business days in advance, and may only take place in one of three designated areas.[68]

- Elizabeth City State University states that the sole “designated area on campus for ‘free speech’ events is the Outdoor Classroom.”[69]

- The University of Massachusetts Dartmouth designates just one area on campus as a “public forum space,” and even requires students wishing to use that space to inform the campus police “at least 48 hours in advance.”[70]

Even where free speech zones have seemingly been eradicated, poor training and policy management continue to cause free speech violations. This past year, students at Western Illinois University sought to hold a demonstration on campus about the decriminalization and legalization of marijuana, a topic the Illinois legislature was debating at the time.[71] Within minutes, the students were stopped by campus police, who told them they were “outside of the free speech zone,” and who promptly shut the event down.[72]

When FIRE contacted the school in September 2019, the administration responded that it had abolished the free speech zone in 2003, and that it would remove current references to the “free speech area” in its policies “as soon as possible.”[73] As of this writing, however, references to the free speech area remain on the university’s website.[74] This confusion underscores the necessity of the requirement from Texas’ free speech legislation that employees who enforce these policies be informed and trained in this area.

Although free speech zone policies are indeed being steadily revised across the country, they continue to pose problems for students’ expressive activities—even when they’ve apparently been taken off the books.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

The good news is that the types of restrictions discussed in this report can be reformed. A student or faculty member can be a tremendously effective advocate for change when they are aware of their expressive rights and willing to engage administrators in their defense. Public exposure is also critical to defeating speech codes, since universities are often unwilling to defend their speech codes in the face of public criticism.

Unconstitutional policies also can be defeated in court, especially at public universities, where speech codes have been struck down in federal courts across the country. Many more such policies have been revised in favor of free speech as the result of legal settlements.

Any speech code in force at a public university is vulnerable to a constitutional challenge. Moreover, as speech codes are consistently defeated in court, administrators cannot credibly argue that they are unaware of the law, which means that they may be held personally liable when they are responsible for their schools’ violations of constitutional rights.[75]

The suppression of free speech at institutions of higher education is a matter of great national concern. But, by working together with universities to revise restrictive speech codes and to reaffirm commitments to free expression, we can continue to make strides toward campuses that truly embody the “marketplace of ideas” that such institutions are meant to be in our society.

Spotlight On: Yellow Light Policies

This year, we were pleased to find that the percentage of schools earning FIRE’s worst, red light rating had declined again, for the twelfth year in a row. While the revision or removal of red light policies is highly encouraging, we remain concerned by the persistence of yellow light policies.

Yellow light policies are vague restrictions or policies that are aimed at a narrower range of speech compared to red light policies. To name just a few examples: At Harvard University, a yellow light policy forces students to submit an application before distributing written materials anywhere on university property.[76] Indiana University Bloomington prohibits “offensive” language or symbols in the residence halls, a policy that would earn a red light rating if its ban extended to the entire campus.[77] At Boston College, students are encouraged to report undefined “bias-related incidents” to administrators for investigation, a vague directive that earns a yellow light rating.[78]

Though they do not earn FIRE’s worst rating, yellow light policies represent a serious threat to expression, and their prevalence warrants a closer look.

Rather than steadily declining like the percentage of red light institutions, the percentage of yellow light schools has increased each year since our 2009 report.[79] This inverse relationship is caused when colleges revise all of their red light policies as a way of doing just enough to earn a yellow light rating, or for some other reason fail to address the yellow light policies that were also on the books.

A total of twenty-six institutions that earned overall red light ratings last year improved their ratings this year, but only two of those schools—Delta State University and McNeese State University—actually improved all the way to earn an overall green light rating. The other twenty-four stopped at an overall yellow light rating, bringing the category to a total of 301 institutions across the country.

So why didn’t those schools finish the job? Perhaps some are still undergoing the revision process—policy revisions can take a good deal of time to develop and adopt, depending on the procedures at a particular school. Others, however, likely see the yellow light rating as being good enough to avoid public criticism and scrutiny. After all, the majority of schools in the database earn an overall yellow light rating, so administrators may see “safety in numbers” and assume maintaining yellow light policies is not unduly restrictive to students or risky with regard to litigation. This assumption is wrong on both counts.

First, yellow light speech restrictions are just that—policies that restrict student expression. Yellow light policies govern a narrower area of speech, like restricting the distribution of flyers instead of all outdoor expressive activities, or depend on administrative application, like a vague bias protocol instead of an outright ban on all biased speech, but this should not breed complacency.

Whether or not these yellow light policies are always applied by administrators in a restrictive manner, their mere presence may have a chilling effect on the expression of students who read them. And where enforcement of policies is selective, you can bet that the expression that will most likely be restricted is the most controversial speech, or speech that challenges powerful figures, like criticism of elected officials or of the college administration itself.

While red light policies are clearly restrictive as written, yellow light policies can be applied to have the same restrictive effect on a student’s expression. Therefore, FIRE’s yellow light rating must not be mistaken as an indication that a policy’s enforcement will result in a less significant free speech violation than the enforcement of a red light policy.

Second, if a moral obligation to live up to the First Amendment—or, in the case of private institutions, to live up to their free speech promises—isn’t enough for administrators, there’s also their legal obligation. Yellow light policy language has been struck down by courts as unconstitutional, ultimately costing colleges time and money.

For example, in DeJohn v. Temple University, et al., the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit invalidated the university’s sexual harassment speech code as unconstitutionally overbroad. The Third Circuit explained that the university had failed to limit the policy’s reach to harassing conduct that is objectively severe and pervasive. The court found fault with the policy’s “purpose or effect” standard for harassment, which impermissibly made intentional conduct that did not actually result in harassment punishable.[80]

In spite of this ruling from a federal appellate court, many schools across the country employ such language in their harassment policies, earning yellow light ratings, as the language represents a vague restriction on expression.[81] Notably, Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pennsylvania both have harassment policies in place that use a “purpose or effect” standard, resulting in their removal from the list of green light institutions as of this year’s report.

The continued maintenance of these “purpose or effect” harassment policies—as well as other types of yellow light policies that have been litigated—opens up yellow light public universities to costly First Amendment lawsuits.

For both moral and legal reasons, institutions earning yellow light ratings must revise their policies. FIRE is always happy to work with administrators who wish to know more about how their institutions’ policies can be revised to meet First Amendment standards. This important step will remove restrictions on student expression, while still allowing the policies to address misconduct that does not constitute protected speech.

Appendix A: Schools By Rating

Red Light

Adams State University

Alabama A&M University

Barnard College

Bates College

Boise State University

Boston College

Boston University

California State University - Dominguez Hills

California State University - Fresno

California State University - Monterey Bay

Carleton College

Case Western Reserve University

Cheyney University of Pennsylvania

Chicago State University

Clark University

Clemson University

Coastal Carolina University

Colby College

Colgate University

College of Charleston

College of the Holy Cross

Connecticut College

Dakota State University

Dartmouth College

Davidson College

Delaware State University

DePauw University

Dickinson College

Drexel University

Eastern Illinois University

Emory University

Evergreen State College

Florida State University

Fordham University

Fort Lewis College

Framingham State University

Furman University

Georgetown University

Georgia Southern University

Governors State University

Grinnell College

Harvard University

Howard University

Idaho State University

Johns Hopkins University

Kean University

Lafayette College

Lake Superior State University

Lehigh University

Lewis-Clark State College

Lincoln University

Louisiana State University - Baton Rouge

Macalester College

Marquette University

Middlebury College

Morehead State University

Mount Holyoke College

Murray State University

New Jersey Institute of Technology

Northeastern University

Northern Illinois University

Northern Vermont University

Oklahoma State University - Stillwater

Portland State University

Princeton University

Reed College

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Southeastern Louisiana University

Southern Illinois University at Carbondale

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

Southern Oregon University

Southern Utah University

St. Olaf College

State University of New York - Fredonia

State University of New York - New Paltz

State University of New York - Albany

Stevens Institute of Technology

Syracuse University

Tennessee State University

The College of New Jersey

Troy University

Tufts University

Tulane University

Union College

University of Alabama at Birmingham

University of Alaska Anchorage

University of Alaska Fairbanks

University of Central Missouri

University of Central Oklahoma

University of Houston

University of Illinois at Chicago

University of Louisiana Lafayette

University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth

University of Massachusetts at Lowell

University of Miami

University of Montana

University of New Orleans

University of North Texas

University of Notre Dame

University of South Carolina Columbia

University of Southern California

University of Texas at Austin

University of Texas at Dallas

University of Tulsa

University of Wisconsin - Oshkosh

University of Wyoming

Utah State University

Villanova University

Virginia State University

Western Illinois University

Whitman College

Wichita State University

William Paterson University

Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Yellow Light

Alabama State University

American University

Amherst College

Angelo State University

Arkansas State University

Athens State University

Auburn University Montgomery

Ball State University

Bard College

Bemidji State University

Black Hills State University

Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania

Bowdoin College

Bowling Green State University

Brandeis University

Bridgewater State University

Brooklyn College, City University of New York

Brown University

Bryn Mawr College

Bucknell University

California Institute of Technology

California Maritime Academy

California Polytechnic State University

California State Polytechnic University, Pomona

California State University - Bakersfield

California State University - Channel Islands

California State University - Chico

California State University - East Bay

California State University - Fullerton

California State University - Long Beach

California State University - Los Angeles

California State University - Northridge

California State University - Sacramento

California State University - San Bernardino

California State University - San Marcos

California State University - Stanislaus

California University of Pennsylvania

Cameron University

Carnegie Mellon University

Central Connecticut State University

Central Michigan University

Central Washington University

Centre College

Christopher Newport University

Clarion University of Pennsylvania

Colorado College

Colorado Mesa University

Colorado School of Mines

Colorado State University

Colorado State University Pueblo

Columbia University

Cornell University

East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania

East Tennessee State University

Eastern Michigan University

Eastern New Mexico University

Eastern Washington University

Elizabeth City State University

Fayetteville State University

Ferris State University

Fitchburg State University

Florida A&M University

Florida Atlantic University

Florida Gulf Coast University

Florida International University

Fort Hays State University

Franklin & Marshall College

Frostburg State University

George Washington University

Georgia Institute of Technology

Georgia State University

Gettysburg College

Grambling State University

Grand Valley State University

Hamilton College

Harvey Mudd College

Haverford College

Henderson State University

Humboldt State University

Hunter College, City University of New York

Illinois State University

Indiana State University

Indiana University - Bloomington

Indiana University - Kokomo

Indiana University - Purdue University Columbus

Indiana University - Purdue University Indianapolis

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Indiana University South Bend

Indiana University, East

Indiana University, Northwest

Indiana University, Southeast

Iowa State University

Jackson State University

Jacksonville State University

James Madison University

Kennesaw State University

Kent State University

Kentucky State University

Kenyon College

Kutztown University of Pennsylvania

Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania

Longwood University

Louisiana Tech University

Mansfield University of Pennsylvania

Marshall University

Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Metropolitan State University

Metropolitan State University of Denver

Miami University of Ohio

Michigan State University

Middle Georgia State University

Middle Tennessee State University

Millersville University of Pennsylvania

Missouri State University

Missouri University of Science & Technology

Montana State University

Montana Tech of the University of Montana

Montclair State University

New College of Florida

New Mexico State University

New York University

Nicholls State University

Norfolk State University

North Carolina A&T State University

North Dakota State University

Northeastern Illinois University

Northern Kentucky University

Northern Michigan University

Northwestern Oklahoma State University

Northwestern State University

Northwestern University

Oakland University

Oberlin College

Occidental College

Ohio University

Old Dominion University

Pennsylvania State University - University Park

Pittsburg State University

Pitzer College

Pomona College

Radford University

Rhode Island College

Rice University

Rogers State University

Rowan University

Rutgers University - New Brunswick

Saginaw Valley State University

Saint Cloud State University

Salem State University

Sam Houston State University

San Diego State University

San Francisco State University

San Jose State University

Scripps College

Sewanee, The University of the South

Shawnee State University

Skidmore College

Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania

Smith College

Sonoma State University

South Dakota State University

Southeast Missouri State University

Southern Connecticut State University

Southern Methodist University

Southwest Minnesota State University

Stanford University

State University of New York - Binghamton

State University of New York - Oswego

State University of New York - University at Buffalo

State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry

Stockton University

Stony Brook University

Swarthmore College

Tarleton State University

Temple University

Tennessee Technological University

Texas Southern University

Texas State University - San Marcos

Texas Tech University

Texas Woman's University

The City College of New York

The Ohio State University

The University of Virginia's College at Wise

Towson University

Trinity College

University of Akron

University of Alabama

University of Alabama in Huntsville

University of Alaska Southeast

University of Arkansas - Fayetteville

University of California Berkeley

University of California Davis

University of California Irvine

University of California Merced

University of California Riverside

University of California San Diego

University of California Santa Barbara

University of California Santa Cruz

University of Central Arkansas

University of Central Florida

University of Cincinnati

University of Colorado at Boulder

University of Connecticut

University of Delaware

University of Denver

University of Georgia

University of Hawaii at Manoa

University of Hawaii Hilo

University of Idaho

University of Illinois at Springfield

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

University of Iowa

University of Kansas

University of Kentucky

University of Maine

University of Maine at Fort Kent

University of Maine Presque Isle

University of Mary Washington

University of Massachusetts - Amherst

University of Massachusetts - Boston

University of Memphis

University of Michigan - Ann Arbor

University of Michigan - Dearborn

University of Michigan - Flint

University of Minnesota - Morris

University of Minnesota - Twin Cities

University of Missouri - Columbia

University of Missouri at St. Louis

University of Missouri-Kansas City

University of Montana Western

University of Montevallo

University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Nebraska Omaha

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

University of Nevada, Reno

University of New Mexico

University of North Alabama

University of North Carolina at Asheville

University of North Carolina School of the Arts

University of North Georgia

University of Northern Colorado

University of Northern Iowa

University of Oklahoma

University of Oregon

University of Pennsylvania

University of Pittsburgh

University of Rhode Island

University of Richmond

University of Rochester

University of South Alabama

University of South Dakota

University of South Florida

University of South Florida at Saint Petersburg

University of Southern Indiana

University of Southern Maine

University of Texas at Arlington

University of Texas at El Paso

University of Texas at San Antonio

University of Texas at Tyler

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley

University of Toledo

University of Utah

University of Vermont

University of Washington

University of West Alabama

University of West Florida

University of West Georgia

University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire

University of Wisconsin - Green Bay

University of Wisconsin - La Crosse

University of Wisconsin - Madison

University of Wisconsin - Stout

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee

Utah Valley University

Valdosta State University

Vanderbilt University

Virginia Commonwealth University

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Wake Forest University

Washington & Lee University

Washington State University

Washington University in St. Louis

Wayne State University

Weber State University

Wellesley College

Wesleyan University

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

West Virginia University

Western Kentucky University

Western Michigan University

Western Oregon University

Western Washington University

Westfield State University

Williams College

Winona State University

Winston Salem State University

Worcester State University

Wright State University

Yale University

Youngstown State University

Green Light

Alcorn State University

Appalachian State University

Arizona State University

Auburn University

Claremont McKenna College

Cleveland State University

Delta State University

Duke University

East Carolina University

Eastern Kentucky University

Edinboro University of Pennsylvania

George Mason University

Kansas State University

Keene State College

McNeese State University

Michigan Technological University

Mississippi State University

North Carolina Central University

North Carolina State University

Northern Arizona University

Oregon State University

Plymouth State University

Purdue University

Purdue University Fort Wayne

Purdue University Northwest

Shippensburg University

State University of New York - Brockport

State University of New York - Plattsburgh

Texas A&M University

The College of William & Mary

University of Arizona

University of California Los Angeles

University of Chicago

University of Florida

University of Louisville

University of Maryland - College Park

University of Mississippi

University of New Hampshire

University of North Carolina - Pembroke

University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

University of North Carolina Charlotte

University of North Carolina Greensboro

University of North Carolina Wilmington

University of North Dakota

University of North Florida

University of Southern Mississippi

University of Tennessee Knoxville

University of Virginia

Western Carolina University

Western Colorado University

Warning Schools

Baylor University

Brigham Young University

Pepperdine University

Saint Louis University

Vassar College

Yeshiva University

Appendix B: Rating Changes, 2018–2019 Academic Year

School | 2017–2018 Rating | 2018–2019 Rating |

Alcorn State University | Yellow | Green |

Black Hills State University | Red | Yellow |

Bryn Mawr College | Red | Yellow |

California State University - Channel Islands | Red | Yellow |

Carnegie Mellon University | Green | Yellow |

Dakota State University | Yellow | Red |

Delta State University | Red | Green |

Eastern Washington University | Red | Yellow |

Emory University | Green | Red |

Fort Lewis College | Yellow | Red |

George Washington University | Red | Yellow |

Grambling State University | Red | Yellow |

Jackson State University | Red | Yellow |

Kentucky State University | Red | Yellow |

Mansfield University of Pennsylvania | Red | Yellow |

McNeese State University | Red | Green |

Middle Georgia State University | Red | Yellow |

Missouri State University | Red | Yellow |

New York University | Red | Yellow |

North Carolina State University | Yellow | Green |

Northern Arizona University | Yellow | Green |

Northern Kentucky University | Red | Yellow |

Pennsylvania State University - University Park | Red | Yellow |

Salem State University | Red | Yellow |

Sam Houston State University | Red | Yellow |

Texas A&M University | Yellow | Green |

University of Arizona | Yellow | Green |

University of Louisville | Yellow | Green |

University of Michigan - Ann Arbor | Red | Yellow |

University of Michigan – Dearborn | Red | Yellow |

University of Michigan – Flint | Red | Yellow |

University of North Carolina - Pembroke | Yellow | Green |

University of Pennsylvania | Green | Yellow |

University of Rhode Island | Red | Yellow |

University of Southern California | Yellow | Red |

University of Southern Mississippi | Yellow | Green |

University of West Alabama | Red | Yellow |

Utah Valley University | Red | Yellow |

Wake Forest University | Red | Yellow |

Wesleyan University | Red | Yellow |

Western Carolina University | Yellow | Green |

Wichita State University | Yellow | Red |

Appendix C: Schools At Which A Faculty Or Administrative Body Has Adopted A Version Of The ‘Chicago Statement’

Note: Some of the institutions on this list are not rated as a part of the Spotlight database at this time and thus do not fall within this report’s speech code analysis. However, they have been included here in order to provide a full list of the institutions at which either the administration or a faculty body has adopted a version of the Chicago Statement. Such institutions are denoted with an asterisk.

American University

Amherst College

Appalachian State University

Arizona State University

Ashland University*

Board of Regents, State of Iowa

Brandeis University

California State University – Channel Islands

Chapman University*

Christopher Newport University

Claremont McKenna College

Clark University

Cleveland State University

Colgate University

Columbia University

Denison University*

Eckerd College*

Franklin & Marshall College

George Mason University

Georgetown University

Gettysburg College

Johns Hopkins University

Joliet Junior College*

Kansas State University

Kenyon College

Kettering University*

Louisiana State University

Miami University of Ohio

Michigan State University

Middle Tennessee State University

Nevada System of Higher Education

Northern Illinois University

Ohio University

Ohio Wesleyan University*

Princeton University

Purdue University

Ranger College*

Smith College

South Dakota University System

State University of New York – University at Buffalo

State University System of Florida

Stetson University*

Suffolk University*

Tennessee Technological University

The Citadel*

The City University of New York

University of Arizona

University of Arkansas at Little Rock*

University of Central Florida

University of Colorado System

University of Denver

University of Louisiana at Lafayette

University of Maine System

University of Maryland

University of Minnesota

University of Missouri System

University of Montana

University of Nebraska

University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

University of Southern Indiana

University of Texas at San Antonio

University of Virginia College at Wise

University of Wisconsin System

Utica College*

Vanderbilt University

Washington and Lee University

Washington University in St. Louis

Winston-Salem State University

Appendix D: Schools With ‘Free Speech Zones’

Arkansas State University

Auburn University Montgomery

Bemidji State University

California State University - Bakersfield

California State University - Dominguez Hills

California State University - Los Angeles

Cameron University

Cornell University

East Tennessee State University

Elizabeth City State University

Evergreen State College

Grambling State University

Kentucky State University

Montclair State University

Morehead State University

Murray State University

Nicholls State University

Occidental College

Old Dominion University

Rutgers University - New Brunswick

Saint Cloud State University

Southern Illinois University at Carbondale

Stanford University

Texas Woman's University

The College of New Jersey

Tulane University

University of California - Riverside

University of Central Arkansas

University of Colorado at Boulder

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth

University of Montana

University of North Carolina School of the Arts

University of North Georgia

University of South Carolina Columbia

University of Southern Indiana

University of West Alabama

Valdosta State University

Western Illinois University

Notes

[1] See, e.g., Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518, 519, 528 (1972) (holding that a Georgia statute prohibiting “opprobrious words or abusive language” was unconstitutional because those terms, as commonly understood, encompass speech protected by the First Amendment).

[2] For example, Baylor University’s “Campus Speakers” policy provides: “Speakers whose purposes and methods are basically contrary to the purposes and methods of a Christian university such as Baylor should not be invited. The use of profanity shall not be tolerated.”

Campus Speakers, BAYLOR UNIVERSITY STUDENT POLICIES & PROCEDURES (updated Aug. 18, 2019), available at baylor.edu/student_policies/index.php?id=32253. It would be clear to any reasonable person reading this policy that students are not entitled to unfettered free speech at Baylor.

[3] FIRE has designated the following colleges and universities as “Warning” schools: Baylor University, Brigham Young University, Pepperdine University, Saint Louis University, Vassar College, and Yeshiva University.

[4] See Appendix A for a full list of schools by rating.

[5] The 2009 report and all other past Spotlight on Speech Codes reports are available at thefire.org/spotlight/reports.

[6] Alcorn State University, Delta State University, McNeese State University, North Carolina State University, Northern Arizona University, Texas A&M University, the University of North Carolina – Pembroke, the University of Arizona, the University of Louisville, the University of Southern Mississippi, and Western Carolina University all joined the ranks of green light schools since last year’s report.

[7] Press Release, Found. for Individual Rights in Educ., One million students now attend colleges with FIRE’s highest free speech rating (Feb. 26, 2019), thefire.org/one-million-students-now-attend-colleges-with-fires-highest-free-speech-rating.