Table of Contents

So to Speak podcast transcript: The Antisemitism Awareness Act

Note: This is an unedited rush transcript. Please check any quotations against the audio recording.

Nico Perrino: You’re listening to So To Speak, the free speech podcast brought to you by FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. All right. Hi, folks. Welcome back to So To Speak, the free speech podcast where, every other week, we take an uncensored look at the world of free expression through personal stories and candid conversations. I am as always your host, Nico Perrino. We’re sticking with college campuses this week as we continue to follow the unrest surrounding the Israel-Hamas War.

As of today, Monday, May 6th, we’re seeing around 100 encampments. And The New York Times reports that 2,300 people have been arrested or detained related to the campus protests. Today, we also learned that Columbia University is cancelling its main commencement ceremony over disruption concerns, joining the University of Southern California, which announced last month it was doing the same. Amidst it all, federal government is now trying to pass legislation to tackle antisemitism on campus.

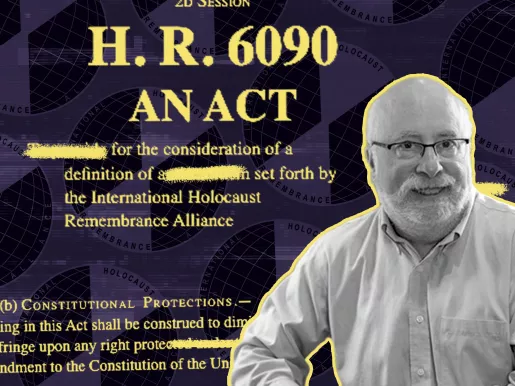

On May 1st, the House of Representatives passed the Antisemitism Awareness Act by a vote of 320 to 91. Versions of the same bill have been proposed for nearly a decade now but have not gotten as much traction as it is getting now, in part due to concerns that the bill threatens free speech rights on campus. That’s one of the reasons that it hasn’t gotten as much traction as it has gotten now. But the recent protests, of course, have changed the political dynamics, and now the Antisemitism Awareness Act has a serious chance of becoming law.

So, what exactly do free speech advocates object to? Well, they argue that the bill would require the Department of Education to use a definition of antisemitism that is vague and overbroad and that includes criticisms of Israeli police when the education department is determining whether unlawful antisemitic discrimination occurred on college campuses. The definition comes from the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, and that definition includes some examples of pure speech that might constitute antisemitism.

Among the examples are denying the Jewish people the right to self-determination, applying double standards by requiring of Israel a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation, drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis, holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the state of Israel, and there are seven other ideas or beliefs that are also spelled out in that definition. So, as free speech advocates have argued, what everyone thinks of these ideas, they are still ideas. And the First Amendment usually protects the expression of ideas no matter how noxious.

To my knowledge, this would be the first time Congress would enshrine in law specific ideas that constitute potentially unlawful bias or discrimination. It has not done so to my knowledge, again, so far for other forms or discrimination such as anti-black racism and sexism, for example. Colleges that fail to consider this definition in meeting their nondiscrimination requirements risk losing all of their federal funding. And most colleges and universities do collect federal funding in one for or another.

It’s for these reasons that folks ranging from Marjorie Taylor Greene to Elon Musk to Jerry Nadler to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to the Alliance Defending Freedom have come out in opposition to the bill. And there’s one other man of note who has come out against the bill. He’s the man who wrote the very definition of antisemitism the bill uses. Our guest today is Kenneth Stern. He was the lead drafter of the IHRA definition of antisemitism, and over the years he has consistently opposed enshrining that definition in law to police speech.

It was designed primarily for European data collectors to be able to craft reports he recently wrote in an op-ed in The Boston Globe. It was never meant to punish speech. Stern is an award-winning author and attorney who currently serves as the director of the Bard Center for the Study of Hate. His most recent book is titled The Conflict Over the Conflict, The Israel/Palestine Campus Debate. A more timely book could not have been written. In this conversation we’re gonna talk with Ken about his career, the campus protests, the IHRA definition of antisemitism, his concerns surrounding using the definition to police speech, and perhaps some more. Ken, welcome onto the show.

Ken Stern: Thank you so much for having me.

Nico Perrino: So, let’s start with your career, Ken. How did you get into addressing issues of antisemitism?

Ken Stern: Well, I started as a trial lawyer in Oregon in the ‘70s and ‘80s working on a lot of criminal defense cases. I represented some of the leadership of the American Indian Movement and the last of the Vietnam era protestors and so forth, but I started becoming concerned about antisemitism. I was seeing it in Portland from the left and from the right. And then I had an opportunity to become the director on antisemitism with the American Jewish Committee in the last ‘80s.

And that was a really great opportunity to take what I was concerned about – hate, antisemitism, and so forth – and not just worry about is a case gonna cross my threshold where I can deal with those issues, but to really think about programmatically what we could do. And one of the first things that I was asked to do when I was at AJC in the late ‘80s was: Help us figure out how to deal with antisemitism on campus. And this was at a time pre-internet days. I went down to a archive in Baltimore that I clipped things that had happened on campus, and I realized a couple of things.

One was that the issues of antisemitism couldn’t be looked at in isolation. You can’t really create rules. This is how we’re gonna deal with Jews on a campus. You have to deal with what the campus should be. And secondly, just like today, people default to simple answers. Ah, let’s have a hate speech code. Let’s figure out what words could be said and what can’t be said.

And what I concluded was a couple things. One was that they were unworkable, not only constitutionally, on a policy level. I mean my favorite of them all was the Michigan one where bright people thought, “Gee, we have different speech issues in the class versus the dining hall versus the dorm. So, let’s have different rules for these different venues.” And to me when I was in college, one of the greatest things about a liberal arts education is we started a discussion in the class. We went over meals and then back in the dorm.

But was it really supposed to stop bigotry when somebody’s drunk at 2:00 in the morning thinking about where they are on the campus and what rules apply? And I really came to the conclusion this was a subterfuge. This was an easy way for campuses to say how we’re dealing with speech rather than looking at the things that could actually have an effect: training of staff, teaching of new classes, surveying of students.

There are a whole bunch of things that the academy’s really poised well to deal with issues of bigotry, antisemitism included. But the allure of thinking, “Ah, we just have a rule. And here are certain words you can’t say, and that’s how we’re gonna deal with it,” was attractive then, and it’s attractive now. And it was a mistake then, and it’s a mistake now.

Nico Perrino: Do you think it can work?

Ken Stern: What’s the “it?”

Nico Perrino: The “it,” like a hate speech code, for example.

Ken Stern: No. No, no, no. I think what it does is it backfires on so many different reasons. First of all, you lose the distinction on a campus, which I think is a critically important one, that every student, regardless of whether they’re in a suspect classification or not, has a reasonable expectation not to be bullied, not to be harassed, not to be intimidated, not to be discriminated against, not to be assaulted, not to be threatened. All those things are... But to hear things that may cut you to the core should be an expectation of what happens on college.

What better place to figure out why somebody has a strongly different point of view? And how do I unpack this? And who’s teaching about it? Where do I learn about it? As opposed to how do we just stop it? And then the other thing it does is it gives the illusion that the administration is actually opposing the antisemitism in this instance, and that’s not really how antisemitism works. It’s not just a question of let’s put something on one line or another and either exculpate or inculpate it.

Antisemitism is a system of thought. It’s a conspiracy theory at heart. It explains what goes wrong in the world, and it is something that isn’t solved by simple problems. And one of the things that I’ve noticed working on issues of hate for decades – and I have a chapter in my book about why human beings go down into these buckets where, as we’re seeing now, people get into the us versus them manifestations that everything is simple, that the other side is evil, that they’re certain about it.

Really, our brains are formed to come to this: Who’s the us? Who’s the them? Who’s the threat? How do we deal with it? And that’s a lot of how the hate is being manifested, but the people that are opposing hate are human beings, too. And we’re seduced by the same sort of, “Ah, here’s a simple answer to a complicated question.” And we’re seduced by symbols of how we should think about these things, and I think the push for the IHRA definition does both of those things. It’s simple as opposed to really articulating how we’re supposed to deal with antisemitism.

And it makes people feel comforted as opposed to: What are the actual concrete things that we’re gonna do to oppose antisemitism? Which is why I like the national strategy, by the way. It came out of the White House last year. It talked about really using all the assets of society, the AmeriCorps, other things to think about how we deal with issues of antisemitism and hatred writ large. Again, it’s just a passing mention to the idea of definitions, and it said, “We’re looking at action, not definitions; but Congress is looking at definitions, not actions.”

Nico Perrino: Yeah. And we’re gonna get to that definition here in a second. You mentioned IHRA, which again is short for the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition. I wanna ask if your analysis of these hate speech codes extends off campus as well. Do you think these codes are not good to use off campus or in Europe. For example, right now, I just read an article in The Wall Street Journal this past weekend, not about the IHRA definition, but about how in France they’re criminalizing the celebration of Hamas’s attacks on October 7th or the suggestion that they might have been warranted. Do you think that’s misguided as well?

Ken Stern: Oh, I think it is. Obviously, Europeans have different speech traditions than Americans. They don’t have the First Amendment. But I think it backfires there as well. And it’s sort of ironic that we’re seeing at the moment here pushes from some on the pro-Palestinian side, pushes at Penn and America and also at a museum in San Francisco saying, “You have to take a pro-Palestinian side.” And I don’t like that as a matter of advocacy, though I understand it.

But the flipside is happening in Germany and France and other places where people are saying if you go and advocate for Palestinian rights and do something that’s, in their view, violative of the definition, you may lose your funding. And a lot of funding for NGOs comes from the government there. So, I’ve talked to people that are very concerned. And this isn’t new. Back, oh, 2016, I think it may have been, give or take, in the UK, they took the definition and applied it to the campus. And there was an Israel Apartheid Week event. And I’m no great lover of Israel Apartheid Week, but it’s speech.

And what happened? They were not allowed to have it because it was violative of the definition. And the Simon Wiesenthal Center here said, “This is great. All campuses should use the definition and now allow this type of speech.” I worry about what happens on campus, off campus. It’s a horrible message. You counter speech with more speech. We could talk about creative ways to do it. But when you want government to censor speech on the campus of off the campus, to me that’s a huge problem, even if you look at our history, McCarthy era, World War I, other times.

Nico Perrino: Well, let’s get into the IHRA definition now. How did you become involved in drafting it, and what was your role?

Ken Stern: Sure. So, I was, as I said, the director on... It became the Division on Antisemitism at the American Jewish Committee. I worked there for 25 years. And at the collapse of the peace process after 2000 and the second intifada, we saw an uptick then as we’re seeing now in attacks on Jews, particularly in Europe. And there was a group called the European Monitoring Center on xenophobia and racism that was tasked to put out reports about such things.

So, they put out a report in 2004 that was pretty accurate in terms of what its findings were. It found that in addition to the usual suspects of white supremacists and others that some of the attacks were from young predominantly Arab and Muslim folks on the outskirts of Paris and so forth. So, the facts they documented were okay.

But then they said, “You know, we have a problem. Problem is that we have all these different data collectors in different countries in Europe, and they don’t have a common song sheet to figure out what to include or what to exclude. So, we need something that would apply across Europe.” And then they said, “Well, for the moment, we’re gonna have a definition that looks at antisemitism as stereotypes about Jews.” And you can make an argument that’s a good or a bad thing, but they basically said that’s what it is. They listed a bunch of stereotypes. And then they went into the political problems.

Well, what do you do if a Jew on the streets of Paris or London or Bratislava or wherever is attacked as a stand-in for an Israeli? Should that be counted as something that’s antisemitic or not? And so, they looked at it and said, “Well, the person had these ideas about Jews and transferred them to Israelis and then retransferred them back to the person in front of them.” That was antisemitism. But if they were just upset at Israeli policy, that was lamentable but shouldn’t be counted in antisemitism and reports.

So, what happened was that a colleague of mine invited the head of the EUMC to be part of a panel at the annual meeting of the American Jewish Committee. And a few weeks before that, there was a firebombing of a Montreal Jewish day school in retaliation for Israel’s assassination of a Hamas leader, so technically not antisemitism according to how EUMC was looking at it. So, you’re not the staff. You’re not supposed to go and confront people that are speakers. It’s mostly for the laypeople to do that, but I did and ended up giving the opportunity.

So, the next month, the head of the EUMC started working with AJC to come up with a tool that could be useful primarily for data collection purposes. There were a couple of other purposes, but that was the goal. And that’s why in the key of the definition were the examples, because they were to guide the data collectors on what to include and what to not include. And some of the examples, as you gave before, were about Israel because we saw a correlation between those statements and what we were seeing on the ground. It wasn’t to label anybody. It wasn’t an antisemite. It wasn’t to be a shortcut.

It was primarily to help data collectors know what to include and what to exclude, and it had also a clarification on hate crimes. We wanted it to take from the Wisconsin v. Mitchell model in the United States to basically say it doesn’t matter if a person really hated somebody or not. If you selected them to be a victim of a crime based on who they are, that’s enough. So, it didn’t matter if you had a pro-Israel, anti-Israel... If you attacked a Jew because he was Jewish, that was the [inaudible] [00:17:12] of a hate crime.

There’s some diplomatic purposes, too. So, I was the lead drafter. Another colleague did the politicking. And then what happened? So, this was 2004, early 2005 they adopted it. 2010, the Department of Education puts out a “Dear Colleague” letter that talks for Title VI purposes, Jews and Sikhs and Muslims are represented there as ethnicities, because it doesn’t include religion as a category in the language of Title VI. And I supported that. I thought it was great.

As a matter of fact, I was a complainant for some Jewish high school students in the outskirts of Binghampton where there was a Kick a Jew Day. The people had swastikas on their desk, and the school district did nothing. And as you said before, theoretically, a Title VI violation could wipe out your funding from the federal government. So, it has some serious teeth. But what I saw is that groups on the pro-Israel largely Jewish right had this great idea in their mind, “Let’s take the definition and particularly these examples about Israel and marry them to the new Title VI powers.”

And so, they started filing cases, and some of them included things that were legitimate to include: spitting, pushing, shoving, those types of things. But they also included, to my great alarm, what was being taught in class, what texts were assigned, what speakers were coming, what a professor was saying, and using it in a way to chill speech. So, what I saw and what prompted me to write the book in 2019 and 2020 was that I saw both sides trying to shut down speech they don’t like.

The pro-Palestinian folks, and it was reported as more ubiquitous than it really was, but were using heckler’s vetoes about Israeli officials or pro-Israel speakers. There was an academic boycott that was being pushed. But on the pro-Israel side, aside from emails to presidents and trustees and so forth, there was a push to use law, and that troubled me deeply. So, that’s sort of the arc of how I got involved in it and why I’ve been so opposed to using it this way. It’s not the language or the definition that’s the problem. It’s the abuse of the definition that’s my concern.

Nico Perrino: Yeah. And let’s step back here to kind of hold our listeners’ hands a little bit through some of the terms you were talking about there. Title VI is from the Civil Rights Act from the 1960s, and it bans discrimination in education and all institutions that receives federal funding. It bans discrimination based on race, color, and national origin. And there was this perception in the 2000s that it didn’t clearly prohibit discrimination that was based on ethnicity or religion. It didn’t necessarily reach antisemitism.

So, in 2004, they issued that “Dear Colleague” letter that you mentioned that prohibits discrimination based on actual or perceived shared ancestry or ethnic characteristics or citizenship or residency in a country with a dominant religion or distinct religious identity. So, the idea being that this would also prohibit antisemitic discrimination. Then you have the question of: What is antisemitic discrimination? Right? And that’s where you get these different institutions, government bodies and otherwise, reaching for the IHRA definition of antisemitism.

But Ken, it’s my understanding that this isn’t the only definition of antisemitism out there. The Antisemitism Awareness Act that was recently passed by the House has a specific line if I’m recalling correctly that says the use of alternative definitions of antisemitism impairs enforcement efforts by adding multiple standards and may fail to identify many of the modern manifestations of antisemitism.

So, some of the same reasons for adopting the IHRA definition in the first place for the reporting purposes for which it was drafted are also animating federal lawmakers now to then pick a single definition to help presumably college and university administrators as well as the Department of Education to clearly understand when discrimination happens. So, how should college and university administrators look to antisemitic discrimination? How should they judge it in the absence of an IHRA definition in your mind?

Ken Stern: Well, again, it comes back to the idea: Is somebody being harassed? Is somebody being intimidated? As opposed to: Is somebody hearing something that they don’t like? And I’ll talk in a little bit about the alternative definitions. But for me, a parallel would be, let’s say, we put together a definition of racism that was built for the similar purposes, to take a temperature of racism in American society over time.

One could make the argument that it would be useful to take that temperature to measure things like opposition to the removal of Confederate statues or opposition to Affirmative Action or opposition to Black Lives Matter, but you wouldn’t want to federally enshrine for any purposes on the college or for funding of 501(c)(3)s – and we’re starting to see some pushes in that direction as well. Something that says if you have this position on these political issues, that is going to be considered racism, and it’s gonna have an impact on your discipline and so forth for Title VI purposes. And so, you wouldn’t wanna go down that road on that issue.

And it’s clear the same thing is happening now on antisemitism. One of the concerns for me is that the push here is very similar to what we’re seeing in some of the states, Florida and others, who are saying there are things about gender that shouldn’t be taught because it makes students feel uncomfortable. There are things about race that shouldn’t be taught because it makes students feel uncomfortable. Let’s do that, too. There are things that are being taught that I don’t like, but I fear much more the government defining what can and can’t be taught in the way that if we look back at the history of the McCarthy era and so forth.

On the alternative definitions – so, here's the story. The thing that really precipitated the push for this was, again, the 2010 letter and then the IHRA group adopting the text of the 2004/2005 EUMC definition and then deciding to push it. And they’ve gotten sports teams and various different governmental officials here and there to adopt it. Then you started seeing primarily Jewish studies professors and Israel studies professors, predominantly Jewish, who were concerned about how it was being abused against pro-Palestinian speech not only as a matter of policy, but reliably as a concern about...

Is the Zionist Organization of America or others gonna come in and see what I’m teaching? And am I gonna have to defend a lawsuit on that, or is my school gonna have to defend a lawsuit? So, there were a couple of intellectual exercises to come up with different definitions. There’s the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism, which I think is much inferior in terms of looking at hate crimes. The language there is much better in IHRA, but it’s much less susceptible to be abused for the purposes of stopping pro-Palestinian speech.

There’s the Nexus definition. In Nexus, we give them an academic home. At Bard, we don’t ascribe to any definition or other. And there’s also the National Strategy really in some ways has its own definition as well. But the point is I don’t want any of these definitions used as a hate speech code. So, it’s not a question if you use this or that one. You don’t decide to have a filter to look at speech of what’s gonna be allowed and what’s not that’s based on politics. The difference is true threats and so forth.

And what I’ve been telling people who’ve been saying, “Well, this and this, these things are awful that we’re hearing.” I said, “Yeah, a lot of them are awful that we’re hearing.” But I go back to David Duke who I remember... Many listening may be too young. But David Duke was a leader of the Klan. He actually was elected as state legislator in Louisiana and ran for statewide office a couple of times. And so, I wrote a background report on him when I was at the American Jewish Committee and included it when he was a student, and he was a student at LSU in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

And what did he do? He first went on a program and said every black person should be shipped back to Africa, and every Jew should be exterminated. And then the next year he actually paraded around campus or at least in their free speech spot with a Nazi uniform. He was vilified, correctly so. And I think he would have loved it if he was disciplined because it would have made him a free speech martyr, but instead he was vilified for what he did. And the wisdom at the time was not to give him that victory, and that’s what’s happening now.

Instead of really stopping speech that people don’t like, it’s making people First Amendment martyrs. And that’s part of the tension that we’re seeing on campus now, the DeSantis stopping students for Justice in Palestine, Brandeis suspending them not for anything they did but for their speech. And to me, that makes a difficult situation even worse.

Nico Perrino: So, when you look at the situation on college campuses right now... FIRE hears from folks all the time who say that there is unlawful antisemitic discrimination and harassment happening on campuses, and often the people we’re hearing from don’t have a conception of what the law is surrounding harassment, true threats, things of this sort. And what’s happening in their mind is a mix of shouts of, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” The implication being that Israel would be eradicated and Jews would be killed. They’re hearing shouts of “Intifada.”

And they’re also seeing videos, for example, of Jewish students being interrogated based on their identity and beliefs and prevented from accessing certain otherwise public areas of campus by these vigilante protest policers. What we’ve always said is that context matters when you’re talking about any of these situations, and you can’t really paint with a broad brush. You need to look at the specific facts. How do you see the situation on campus right now? Are you seeing a rise in increases of what you would consider unlawful harassment and discrimination? And where do you distinguish between pure political speech and unprotected conduct of that sort?

Ken Stern: It’s a great question, and there’s no question that there’s been an uptick in antisemitism. And also, when I go on campuses, I also speak to others including Muslim students and Palestinian students and professors and so forth. There’s an uptick there, too. Let’s not forget that there were the doxing trucks that went around Columbia and Harvard and so forth right after October 7th. But yeah, it’s difficult. It’s difficult for Jewish students for whom their identity is tethered to Israel, a Zionist. And I’m a Zionist. I get it. I don’t like a lot of those chants, too.

But there’s a fundamental between hearing those chants and then the things that you were describing: blocking somebody’s ability to go into a different area, singling them out for different treatment. “From the river to the sea,” I get why people are concerned about it, but there’s a difference between just expressing that as a chant and maybe going to somebody’s dorm or a Hillel building and doing that in a threatening way. So, despite the fact of that awful December 5th hearing, context does matter, as you said. It really does, to be able to ferret out what’s happening and what’s not.

Nico Perrino: And the December 5th hearing, for our listeners who don’t get that reference, is when the presidents of MIT, Penn, and Harvard testified in front of Congress and Congresswoman Elise Stefanik asked them if calls for Jewish genocide were prohibited by their campus policies. This immediately followed her questioning of them on chants like, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” and, “Intifada.”

Ken Stern: That’s correct.

Nico Perrino: And she of course asked them to respond in one word, which when you’re talking about unprotected speech is almost never possible.

Ken Stern: That’s right. I think a lot of them would have liked to have that moment back in terms of how they answered to it, but it’s also with some sympathy. It was five hours into a hearing, and it was a loaded question precisely as you said because A.) “From the river to the sea,” people hear that differently. I find that when Hamas says it, I know what it means. But I also know that, like most of these things, it’s more complicated. There was a poll that came out that 66% of Jewish students heard “From the river to the sea” as a call for genocide against Jews and the elimination of Israel. Only 14% of Muslim students thought that that’s what it meant.

You look at the history, the Likud government in 1977 talked about “From the river to the sea” for the Jewish sovereignty. It does get complicated. And even if one for the sake of argument said, “Okay. It’s cut and paste. A hundred percent of the time that’s what people mean.” If you have just an abstract call for genocide, that should be roundly condemned. You should really push back against that with all the resources of the university except for discipline, unless it’s a true threat. I mean there have been cases.

Years ago, there was one in California where somebody found every Asian sounding name in email and sent them an email saying, “I’m gonna make it my mission in life to hunt you down and kill you.” Convicted correctly. If he just got up and said, “I think fill-in-the-blank should die,” that’s protected. It doesn’t’ mean there’s a dichotomy here which people... It drives me crazy. I think of either you discipline it, or you don’t do anything. And there’s a lot of things that you can do. I’ll give you an example. You talked before about outside of the classroom context.

In late 2016 and early 2017, there were some Neo-Nazis that were threatening the Jewish community in western Montana. And there was one guy that was gonna do an armed march on Martin Luther King Day and bring up skinheads, and he was threatening the human rights folks, too. He didn’t stop the speech. What did we do? We used social media. We got people to make pledges tied to if these guys marched, how long that they would march for. They would be raising money for things they detested and turn their free speech rights on their head.

They would be raising money for antibias education and for police training on hate crimes, security for the Jewish committee, give the community there a feeling that others outside had their back and gave people outside the community something to do other than put a like on Facebook. So, there were lots of strategies to deal with speech you don’t like, but people think either you let it fly or you discipline people. And it really blinds us to all these other opportunities.

Nico Perrino: You know, I appeared in the wake of that December 5th hearing on Jake Tapper’s show on CNN and was asked about the hearing and whether calls for Jewish genocide should be prohibited by campus policies. And it should be noted that when the president of Columbia last month went in front of Congress and was asked that same question, she essentially said, yes, it is prohibited by campus policy, probably understanding the consequences of two of the three presidents who had appeared in front of that panel prior and answered that context matters.

But we’ve seen this time and time again on college campuses where these vague, overbroad, or abstract speech codes are used to punish core protected speech. So, right now, pro-Palestinian students are accusing Israel of committing a genocide. Would support for Israel’s war be a call for genocide? You could imagine many protestors would try to wield such a speech code in that manner. You see a big debate right now about gender-affirming care for trans kids.

And folks who oppose the efforts to ban gender-affirming care are saying that those efforts are genocides against trans kids. You see pro-lifers argue that abortion is a genocide against the unborn. You can just see how if you untether these speech restrictions from the law, they can be wielded by partisans on all sides to go after their political opponents. And I think back to the origin story of FIRE, which was the story of Eden Jacobowitz. He was a student at the University of Pennsylvania in the ‘90s studying for finals in his dorm room.

There was a ruckus happening outside late at night while he was trying to study. He shouts out his window, “Shut up, you water buffalo.” It turns out to be a black sorority. And he is an Israeli, native Hebrew speaker. My understanding is that behema in Hebrew roughly translates to water buffalo, and he was just doing the rough translation in his head. But Penn wielded its hate speech code or its bias code to go after him. And that’s what happens when you use these tools or put these tools in place. They end up being subjectively wielded against protected speech.

Ira Glass or the former ACLU executive director tells this story. I’ve never actually been able to confirm whether it’s true. I’ve done some Google search. But he talks about how the National Union of Students in the 1970s wanted to pass a hate speech code, and the Zionist student organization in that country – this is in England – supported them. And a couple of years later, the National Union of Students determined that Zionism was a form of hate speech.

And so, this speech code that the Zionist students had supported had ended up backfiring on them. Again, I’ve never been able to confirm that, but I trust it’s true because he was working in the space at the time. But yeah, you have to be careful what you wish for with these speech codes. Right?

Ken Stern: Yeah, exactly. And I was aware of the fact that there was a Jewish student group that was not allowed under the equation that Jews are Zionists, Zionists are racists, and racist groups aren’t allowed. I had not heard that the Zionist group were pushing for that, and it came back to bite them in the butt. But that’s part of what I’ve been arguing on campus, too, where somebody would say, “Well, how can you allow a call for genocide?” My response is exactly like yours.

If you’re a pro-Palestinian person, and you can debate what’s happening in terms of what Israel is doing is or is not technically genocide, but I wouldn’t be shocked. I would be surprised if they didn’t under such a rule say, “Well, this is promoting genocide,” when you’re saying Israel has the right to go after Hamas. And what’s been interesting to me about the legislation the last couple of days is you started having some other folks that are having concerns about it, too. Right? You have Marjorie Taylor Greene and some others that are basically saying... Well, let’s step back for a moment because of the unintended consequences.

The debate over this has promoted a lot more antisemitism because we’re hearing again about Jews killing Jesus right from public officials. And that’s a response to this push for legislation because that is one of the data points that we wanted to collect over time and across borders. But what’s really interesting is you started having some senators saying, “You know, I have a concern about that, too. I don’t think that we should outlaw the Gospels, and this is what this would do.” So, one was talking about, “Gee. Well, if this comes up in the Senate, maybe I’m gonna go and propose an amendment that would strike that particular language.”

Well, that’s, to me, an admission that this is all about speech. If you don’t like that language, then there’s other language about language about Palestinians or about Israel. It’s the same problem. It’s just this is the language that you don’t like, but there are reasons why other people may have a different point of view of what the language that’s problematic is. And the bottom line of all of this is – I grew up in the ‘50s and the ‘60s and the end of the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War time.

The lesson from that time is when you give government the ability to decide what speech is okay and what isn’t, it’s gonna be the speech the government doesn’t like. It’s not the speech that you and I don’t like. And I think people forget that too often.

Nico Perrino: Yeah. I’m reminded of Aryeh Neier, who was the executive director of the ACLU during the Nazis in Skokie case starting in 1977. And he wrote a magisterial book called Defending My Enemy about his reasons for taking that case. And he would get letters saying things like, “If there’s another Holocaust, you’ll be at the front of the line,” suggesting that ACLU’s new motto should be, “First Amendment uber alles.”

And the reason he wrote the book was to explain why he, a Holocaust survivor himself who escaped Berlin just before war broke out, defended the right of Neo-Nazis to rally in the town of Skokie, Illinois. And he said that the best way he knows of to prevent another Holocaust from happening is to prevent incursions on individual liberty, and that includes incursions on freedom of speech. And unfortunately, that book is out of print, Defending My Enemy, but I’m working with some folks to see if we can’t find a publisher to republish it perhaps with another forward by Aryeh.

But I will say there are a lot of individuals and groups coming out and in opposition to the Antisemitism Awareness Act, including the editors of Tablet, the Jewish publication who published a very striking headline and editorial titled, “Not in Our Name,” with the sub-headline saying, “Politicians are using the rise in antisemitism as an excuse to curtail free speech and expand their own power. Jews must not let them.” So, it’ll be interesting to see what happens when you even have segments of the Jewish community coming out in opposition to this definition.

Ken Stern: Oh, yeah. We have a lot of segments of the Jewish community, a lot of the progressive groups that have come out against this, J Street and other as well because they see that this is not just a simple solution to antisemitism. It’s likely to make it worse. Again, it blinds us to what actually drives antisemitism, and it makes us feel more comforting. In South Carolina a few years ago, the state adopted the definition.

And it was interesting. In the debate leading up to it, there was a rabbi who wrote a piece that basically said, “Look, Hitler didn’t kill anybody with his own hands. The way he did it was through words. We have to stop these words.” And I wrote something along with the formal general secretary of the AAUP and said, “We don’t disagree. Worrds have consequences. But if you’re looking at what made the Nazis possible, it was because they suppressed speech. They defined what was okay and what wasn’t okay to believe, and that was a driving force.” Interesting.

I wasn’t around at the time of the Skokie case. Of course, I remember it in the news as a much younger person. But I talked to people in the Jewish community who were around at the time. And internally, what they were trying to say was don’t try to stop them from marching. You’re gonna give them free publicity. There are ways of dealing in the community. Again, there’s some sensitivity with Skokie. It was a community of Holocaust deniers. I get the sensitivity.

Nico Perrino: Holocaust survivors, yeah.

Ken Stern: Yeah. But what happened was it gave these guys tremendous press, and it backfired. I can give you other instances where people feel just so passionate about, “They shall not speak.” They don’t look at the strategy. Again, I’m not saying to ignore them in every case. But in this case, it would have been just a couple of people there, and they got a tremendous amount of free publicity. And really, as you rightly said, it created some problems for people in the leadership at the ACLU who took a very principled stance and I think a correct one at the time.

Nico Perrino: Well, let’s address some of the defenses of the Antisemitism Awareness Act that I’ve seen. There might be others, but there are principally two. One is that it has what we call in the First Amendment world a savings clause. It says at the end, “Nothing in this act shall be construed to diminish or infringe upon any right protected under the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.” What do you make of that?

Ken Stern: I think, well, disingenuous doesn’t even begin to describe it. And it’s not just a question of we’re gonna put restrictions on this, but we’re gonna put this little section at the end that says it’s really not unconstitutional. The thing that I see as the real problem of this on the campus is not necessarily how the cases are gonna be litigated. It's about the chilling effect. It’s about the pressure on administrators who know that there are groups out there hunting for speech to file Title VI cases, and their job is to protect the university from being sued.

So, they are gonna try to suppress speech. They’re gonna try to chill speech to protect the institution from these lawsuits. There was a situation at Barnard a while back where they wanted to show the film Israelism. They were ultimately allowed to watch it, but initially they weren’t because there was a suit I believe at Harvard that had had among it’s allegations in a Title VI case the showing of the film Israelism. That’s the point. I mean Ken Marcus, who’s head of the Brandeis Center, was at the Department of Education, has really pushed this type of legislation for a number of years now, wrote a piece when all the cases were failing. All the Title VI cases were losing that were using the push.

And he said, “Well, at least it’s got administrators to take notice. At least it gave a counterforce to the pro-Palestinian organizing.” He defined it as antisemitic organizing. But it was all about speech, and that to me is the major thing. So, the savings clause does nothing. Again, imagine if one had enshrined in legislation opposition to Affirmative Action is racism, period. You have to consider that when you’re looking at campus life and other things. But we’re protecting the First Amendment. You can’t do two things at the same time on that context.

Nico Perrino: Yeah. Savings clauses are something that First Amendment advocates often roll their eyes in, because any time a legislator gets an inkling that their legislation might chill or prohibit or punish speech they introduce one of these savings clauses. And judges have looked very skeptically at these. At the very least, it creates a vagueness problem within the piece of legislation. It’s like you have this whole piece of legislation that chills speech, and then you put a line at the end and says it doesn’t chill speech.

Ken Stern: It’s like, never mind.

Nico Perrino: Never mind. Just ignore everything that came before it. But then it’s like, what is the legislation doing? So, judges look very skeptically at that. But when I look at criticism of the opposition to this act online, that’s often what it falls upon. It also falls upon the argument that you’ve just kind of addressed which is that it doesn’t police speech. The examples and the definition are simply something that should be considered as part of the pattern of discriminatory behavior.

Ken Stern: Yeah. I was asked that question by Chairman Goodlatte in the 2017 hearing. He said, “Well, you know, just as considering it.” I said, “Look, when you enshrine any definition in law, it prioritizes that is the speech you don’t like. And that puts a thumb on the scale, and it’s not without consequence for all the reasons that we said.” And there’s a third argument that I’ve seen proponents push. It goes, “You know, to combat antisemitism, you have to define it.” Well, I’ve worked with the American Jewish Committee for 25 years. There was no definition until 2005. The AJC had been founded in 1906. The ADL has been around since the early 1900s, too.

Nobody said we needed a definition to fight it, and I thought we did. All the groups have done a fairly decent job without having a definition. Nobody says we need a definition to... Kanye West said, “Let’s go DEFCON 3 on Jews.” What does IHRA say about that? We don’t do that. This is only about pro-Palestinian speech. And now we’ve got the example, too, of, well, it’s about what you can say about the Gospels. It’s about speech. It’s not about defining antisemitism. People were really concerned about antisemitism. Antisemitism at its heart – and all the definitions have this in different words.

At its most significant, it’s conspiracy theory charging Jews with harming humanity and giving an explanation for what goes wrong in the world from the killing of Jesus to the blood libel about Jews stealing Christian babies to the poisoning of wells to Marjorie Taylor Greene and her Jewish space lasers creating forest fires in California. That’s what antisemitism is, but it’s an idea. It’s a theology in part, an ideology in part, depending on whether it’s a militia movement or others, but it’s speech. The focus on it should be what’s driving people into thinking in these conspiratorial terms.

And when we have the narrow lens of is this one side of the line or other side of the line about antisemitism, we lose... One example, Tree of Life, clearly antisemitic. Bowers went and killed 11 Jews. What was the motivating factor for that? A large motivating factor was the hysteria about immigrants coming across the border in the south. And he felt that because the synagogue had hosted a HIAS, meaning Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, a pro-immigration group. This is what he was going to do to stop the influx of invaders.

Nobody would see the shooting of the Walmart in El Paso or the shooting at the Tops in Buffalo, one of Mexican Americans, the other of African Americans, as an instance of antisemitism. But you look at the ideology of the different shooters, the ideology was the same. So, when we have this narrow lens of do we put something on one side of a line or another about antisemitism, we lose so much about how it works.

Another example, I wrote a book about the militia movement after the Oklahoma City bombing, and I quoted the head of the Montana Human Rights Network. And Montana was one of the ground zeroes of the militias. He used a great metaphor. His name is Ken Toole. He said this was a funnel moving through space. And what he meant by that was that people were being sucked into the militia movement by mainstream issues at the time: gun control, federal land use planning, and so forth. And once they got into these systems where it’s us and them, and these are animating ideas, they get exposed to conspiratorial thinking.

Once they got into that funnel further, they got exposed to the antisemitic conspiracy theories because it’s the all-time go-to way of... It’s why the Charlottesville folks were saying, “Jews will not replace us.” Why are you losing as a white supremacist to people who aren’t white? Jews are behind the scenes making this happen. So, those are the things that concern me at the moment.

What’s driving antisemitism? Clearly, some of the stuff on the campus, but moreso when we’re in society and leaders in particular are saying, “There’s anybody among us who deserves to be vilified that’s a danger to us.” Putting people and priming that pump and saying it’s okay to hate somebody among us as a danger is putting people on a conveyor belt to antisemitism. That’s where I find it most frightening. And when we’re just looking at does this fit into a definition or not, we lose so much about what’s actually driving antisemitism today.

Nico Perrino: Yeah. One of the other retorts that we get when arguing against the IHRA definition is that it’s been enshrined in various state laws. You had mentioned South Carolina, also Florida. Texas Governor Abbott had enshrined it in the executive order. Trump put it in an executive order in 2019. And the argument goes, well, has it been used to censor speech? And we at FIRE have seen it used to censor speech or at least make the arguments to censor speech. You brought up Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue shooting.

There’s a lawsuit, I believe, or at least a Office of Civil Rights of the Department of Education complaint stemming out of Berkely because students perceived a vigil at that school that jointly commemorated the deaths of the 11 killed at the Tree of Life shooting along with three Gaza children who were killed by an Israeli military strike, the fact that they were hosting those together in a vigil was an antisemitic act that runs afoul of “the definition of antisemitism that was recently adopted by the DOE.” That is the IHRA definition.

We’ve also seen, for example, at San Jose State University a presentation or a lecture was gonna be presented called “We Will Not Be Silenced, the Academic Repression of Israel’s Critics.” The administration there opposed it under the IHRA definition or at least in part under the IHRA definition. You saw the Zionist Organization of America demand that the University of Michigan issue a stronger response to comparisons or Israelis to Nazis and label those comparisons as antisemitic as the U.S. government does in its working definition of antisemitism, which of course is the IHRA definition.

And you see that definition wielded in lawsuits against colleges and universities across the country. Harvard in the Kestenbaum, for example, the IHRA definition is cited. And you also say our Rep. Brad Sherman of California contend that the National Students for Justice of Palestine website runs afoul of state department definition – this is the IHRA definition, which the state department uses for tracking purposes – and thus arguing that UCLA should not be able to host a Students for Justice in Palestine conference. So, to the extent there are arguments out there that it isn’t being used to police speech, we’ve been seeing it.

Some of these arguments work; some of them don’t. But people see it as a tool, as we had mentioned before, to go after their political opponents. So, I also wanna ask you about one last criticism we got, which is kind of the definition of itself. Ryan Grim’s a journalist. He argues that the definition itself is internally consistent. And I guess one of the lead drafters might be able to respond to that. He says that, broadly, it includes within it its examples, criticism of Israel as being antisemitic.

He says but when you’re looking at the Antisemitism Awareness Act, it says anything “holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of Israel” is banned. So, it says lumping in Jews with Israel is antisemitism, but it also bans holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of Israel. So, he says it’s a law-breaking law. What do you make of that as well?

Ken Stern: Well, again, to go back to the intent of the definition, it was to try to help people who are collecting data to think through things that can affect the temperature of antisemitism at a time. So, the exercise wasn’t a question of internally consistent. It was to take these things that may be data points to correlate with some of what was happening on the ground. So, again, to look at it from the point of view of what the definition says or doesn’t say misses the question of how it’s actually been abused. To give you another example, you cited about the double standard.

The intent of the double standard was to think that Americans would not be expected to be silent and do nothing if Canada was lobbing bombs into Buffalo, but there were criticisms of Israel for responding to things that happened in Gaza. But how does that get twisted? It got twisted by saying, well, if you don’t call out all these other types of horrible things that are happening in the world and only focusing on Israel, that’s antisemitism. That’s been included in some of the allegations about this. When I was protesting for Soviet Jewry, nobody was saying I was anti-Tibetan for not also going with the Tibet demonstrations.

So, again, we can focus on the language and what it means, but the point is that people are using it as a weapon, taking it out of context, thinking it’s a simple thing to try to stop speech, and it becomes incredibly ridiculous. I mean you were talking about the lawsuits. There are others that have happened using IHRA to try to stop people from speaking. I saw the one at Penn, and there were things there that concerned me. I’m not gonna make a judgment about the whole –

Nico Perrino: Yeah. Often, protected speech is lumped in with theory as discriminatory conduct.

Ken Stern: I found it very ironic that one of the things that they complained about using, if I recall correctly in the context of IHRA, was a teach-in on a university campus.

Nico Perrino: Yeah, right.

Ken Stern: You might not like what’s being taught, but to say that that violates Title VI as somebody’s teaching is nuts. And then I wrote a piece for The Boston Globe recently and talked about the Tennessee legislation, which was very interesting because you had a bill that passed to prohibit the teaching of antisemitic concepts tying into the IHRA definition, clearly looking at funding as a risk. But the person who the Jewish community got to promote it was the same person who promoted a bill to make the Bible the official book of Tennessee and also a bill to take out books from libraries that were age inappropriate.

And when asked, “What do we do with these books?” his response was, “Burn them.” So, when you make common cause with somebody who even maybe even jokingly saying, “Okay, this is what we do with books we don’t like.” It’s the same thing with ideas that we don’t like. And again, that backfires. It will not help us fight antisemitism. And again, it sucks all the energy out of looking at the creative things that we can do. It's like a blackhole to take away any notice from the things that we could actually be doing, a lot of which are in the National Strategy, a lot of them on the campus.

The last chapter in my book, The Conflict Over the Conflict, I have courses and other things that would actually help the moment, including on Israel-Palestine, antisemitism, the importance of students recognizing what free speech means and academic freedom means because there are too many pushes to get students to think, “Oh, if I hear something I disagree with, I have to be protected from that,” as opposed to, “Okay. Why does somebody have this entirely different perspective? And how is the university gonna help me unpack that?” So, there are a whole bunch of things that one can do, but we’re seduced by the idea of: Let’s just get government to stop speech we don’t like.

Nico Perrino: We’re about at time here. Last question, if you can take out your crystal ball and in about 30 seconds maybe predict what’s gonna happen with this in the Senate, what would you put your money on right now?

Ken Stern: I don’t know. My expertise is not all the different legislative offices and who the pushes and pulls are on this, but I find it very interesting, as you said, that there’s a coalition, still, from what I saw in 2017 when I testified, in the way of people that may be on the right who get the free speech issues, people on the left who may get the free speech issues, and then those who politically for other reasons feel, “Okay, for understandable reasons, antisemitism is an issue. This is what’s being asked. I gotta take that stake.”

But then we have thrown into the mix the Marjorie Taylor Greenes of the world who are basically saying this is gonna outlaw the teaching of the Gospel. And I suspect that that will complicate things. What I really hope is that: A.) This doesn’t pass, and B.) That you don’t have a lighter version of this passing, and C.) That some of the indications that I’ve seen to model after what the Europeans are trying to push in various different ways of going after who can be a 501(c)(3) and not.

I mean there are a whole bunch of Pandora boxes that I’m worried about here, but I hope the attention from this moment turns into: Okay, what can we actually do about antisemitism? Why are we not funding some of the things that I think have the potential to be very effective from the National Strategy? Why are we always looking for the easy answers? If that opens up the conversation, that’ll be a good thing, but I am worried that it might pass.

Nico Perrino: Well, Kenneth Stern, I appreciate you coming on the show and lending your insight. It’s been a pleasure.

Ken Stern: Thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate it.

Nico Perrino: That was Kenneth Stern. Ken is the director of the Bard Center for the Study of Hate and author most recently of a very timely book, The Conflict Over the Conflict, the Israel-Palestine Campus Debate. This podcast is hosted by me, Nico Perrino, and produced by Sam Niederholzer and myself. It’s edited by a rotating roster of my FIRE colleagues including Aaron Reese, Chris Molpie, and Sam. You can learn more about So to Speak by subscribing to our YouTube channel.

Videos of these conversations are hosted there. You can also follow us on Twitter by searching for the handle freespeechtalk. We take email feedback. If you wanna provide it, you can email us at sotospeak@thefire.org. And if you enjoyed this episode, please consider leaving us a review on Apple Podcast, Google Play, Spotify, or wherever else you get your podcast. They do help us attract new listeners to the show by juicing their algorithms. And until next time, I thank you all again for listening.