Table of Contents

Why Julian Assange couldn’t outrun the Espionage Act

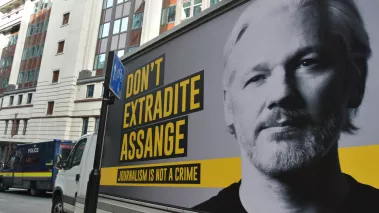

Katherine Da Silva / Shutterstock.com

Mobile billboard in London on Sept. 7, 2020, the first day of the extradition case of Julian Assange versus the United States.

Julian Assange is a free man, and one of the most contentious press freedom controversies in living memory may finally be coming to a close.

The WikiLeaks founder reached a plea deal with the Department of Justice on Monday after spending five years in an English prison fighting extradition to the United States. Federal officials sought to charge Assange with conspiracy to obtain and disclose national security information under the Espionage Act of 1917.

Assange and WikiLeaks shocked the world in 2010 by publishing hundreds of thousands of secret military documents and diplomatic cables related to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that were leaked by Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning. Months later, Assange was on the run and Manning was in jail.

Assange claimed that by receiving and publishing confidential information, what he did was no different than the type of routine news reporting that journalists around the world engage in every day. As the Supreme Court ruled in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), better known as “The Pentagon Papers” case, publishing leaked documents is protected under the First Amendment.

FIRE has long opposed use of the Espionage Act to curtail the rights of journalists to source information. And in December 2022, FIRE signed an open letter organized by the Committee to Protect Journalists along with 20 other civil liberties groups calling on the federal government to drop its charges against Assange.

“We are united . . . in our view that the criminal case against him poses a grave threat to press freedom both in the United States and abroad,” we argued. “[J]ournalists routinely engage in much of the conduct described in the indictment: speaking with sources, asking for clarification or more documentation, and receiving and publishing official secrets. News organizations frequently and necessarily publish classified information in order to inform the public of matters of profound public significance.”

Assange’s 12 year ordeal, including seven years in self-exile in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London before his arrest and imprisonment, underscores the continued threat that the century-old Espionage Act still poses to civil liberties today — and not just in the United States. Assange is not a U.S. citizen, nor was he ever a resident. But because of modern extradition treaties, there were few places in the world where he could travel to escape the Act’s reach.

Though Julian Assange is finally free, FIRE continues to have serious concerns about the grave threat the Espionage Act poses to journalism and the First Amendment.

Under the terms of Monday’s deal, Assange pleaded guilty to the charges and was sentenced to 62 months incarceration, but with credit for time served, according to documents filed with the U.S. District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands.

Ultimately, freedom of the press is what was at stake with the government’s case against Assange. It was never only about him. The precedent that would have been set by his extradition and trial would have sent a chilling message to journalists across the country and the world: You can run, but you can’t hide from the Espionage Act.

What is the Espionage Act?

On Dec. 7, 1915, President Woodrow Wilson stood before a joint session of Congress to deliver the State of the Union Address. Although it would be nearly two more years until the country joined the fight in World War I, national security was top of mind for the first-term president seeking reelection.

The war in Europe was raging. With sizable immigrant communities from all nations involved in the fighting now residing in the U.S., Wilson thought it best to declare the country neutral to maintain domestic peace. At the same time, however, he viewed immigrants with suspicion.

“There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags but welcomed under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life,” he said to Congress. Should these individuals ever gain access to sensitive military information, he suggested, it could endanger national security.

So to Speak podcast: The 100th anniversary of the Espionage Act of 1917

It was 100 years ago this month that the Espionage Act of 1917 was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, making it a crime to interfere with the operations of the United States military.

“We are without adequate federal laws to deal with” espionage, he said. “I urge you to enact such laws at the earliest possible moment and feel that in doing so I am urging you to do nothing less than save the honor and self-respect of the nation.”

That’s exactly what Congress did two years later after the country became involved in the war. Based on the Defense Secrets Act of 1911, the Espionage Act of 1917 included much stiffer penalties — including the death penalty — for sharing secret or confidential information or otherwise interfering with the operations of the U.S. military.

The Espionage Act made it a crime to obtain information regarding national defense “with intent or reason to believe” that doing so would hurt the U.S. or to advantage another country. While subsequent amendments and court decisions have refined its language and scope, its core purpose remains the same.

Espionage Act and the Supreme Court

The law was immediately controversial because its use was not limited to actual acts of espionage. Rather, the Espionage Act allowed the government to clamp down on anyone who opposed the war effort.

In Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court upheld the conspiracy conviction against socialist Charles Schenck under the Espionage Act for distributing anti-war leaflets that urged people to boycott the draft. The Court’s opinion in Schenck was the first articulation of the “clear and present danger” test, wherein Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. infamously wrote: “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.”

The problem with the Court’s ruling in Schenck, as subsequent decisions would affirm, is that Schenk’s speech was not calling for violence or even civil disobedience. Rather, his speech was precisely the kind of political expression that decades of subsequent Supreme Court decisions would ultimately uphold. Numerous convictions under the Espionage Act would make their way to the Court, including that of socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs, who was arrested for giving a speech opposing the war.

SCHENCK v. UNITED STATES

Charles Schenck was charged with conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act for distributing anti-war leaflets that urged people to boycott the draft.

Since then, one of the most nefarious uses of the Espionage Act has been to silence journalists. At least insofar as publishing the leaked documents on the Wikileaks website, what Assange did was little different than what The New York Times and The Washington Post did in 1971 when they published and reported on thousands of pages from a classified report about the war in Vietnam.

Just days after the Times published the first of many articles on the Pentagon Papers, as they came to be known, the federal government asked for a restraining order that would have prevented the publication of subsequent articles based on the leaked documents. Attorney General John N. Mitchell cited the Espionage Act as the basis for the order. The Times challenged the order, and the case eventually made it to the Supreme Court.

“In seeking injunctions against these newspapers and in its presentation to the Court, the Executive Branch seems to have forgotten the essential purpose and history of the First Amendment,” Justice Hugo Black explained in the concurring decision. “The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.”

As the Supreme Court has ruled, freedom of the press is a foundational principle, enshrined in the Bill of Rights. And though Julian Assange is finally free, FIRE continues to have serious concerns about the grave threat the Espionage Act poses to journalism and the First Amendment.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

LAWSUIT: Ex-cop sues after spending 37 days in jail for sharing meme following Charlie Kirk murder

Can the government ban controversial public holiday displays?

DOJ plan to target ‘domestic terrorists’ risks chilling speech