Table of Contents

Why did a Bellevue College administrator censor an art installation memorializing Japanese-American internment camps? Public records suggest a motive.

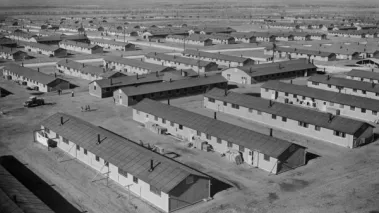

An internment camp for Japanese Americans during World War II, the Granada War Relocation Center in Colorado. Administrators at Bellevue College in Washington have come under scrutiny in recent months for allegedly censoring an art installation commemorating these kinds of camps.

In February, Bellevue College’s vice president of advancement, Gayle Barge — or someone acting on her behalf — took white-out to erase words from an art exhibit memorializing Japanese-American internment camps. The act of censorship was so brazen that it led to an abrupt, inglorious end to the college’s relationship with not only Barge, but its president.

As the Seattle Times reported at the time:

Barge, who last week was placed on leave, acknowledged two weeks ago that she removed a reference in the description accompanying the art installation “Never Again Is Now,” created by Seattle artist Erin Shigaki. The project was brought to Bellevue College as the school recognized the Day of Remembrance, which commemorates the day President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

One sentence in a paragraph about Japanese immigrants and their connection to Bellevue was whited out: “After decades of anti-Japanese agitation, led by Eastside businessman Miller Freeman and others, the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans included the 60 families (300 individuals) who farmed Bellevue.”

Censorship — including the suppression of art on campus — rears its ugly head in various forms, some clearer than others. Physically erasing words from public view is about as stark an example of censorship as they come.

While it’s often easy to attribute a motive to most censors, Barge’s whitewashing was dumbfounding. Why would anyone, much less a senior college administrator, be so motivated to protect the public’s opinion of someone who died in 1955 that she would deface an art installation? Was the decision — as some have speculated, noting that Barge’s role made her responsible for “all fundraising, marketing and communications outreach” for the college — related to a prospective donor?

As it turns out, Miller Freeman left behind not only a disreputable legacy, but a wealthy progeny, including a billionaire grandson, Kemper Freeman, Jr.:

Love him or hate him, it’s hard to avoid Freeman’s presence in Bellevue, a well-off city of about 130,000 people directly across Lake Washington from Seattle. He operates 4 million square feet of retail, office towers, hotels and luxury residences that have anchored the city’s transformation from a sleepy hamlet into one of America’s wealthiest enclaves, with Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos among the billionaires living nearby.

Public records produced to FIRE suggest that Barge and Bellevue’s administration were keen on earning the support of the Freeman family, and were quite focused on avoiding embarrassing them.

These records include Bellevue College’s efforts to respond to the criticism, as administrators initially worked to defend one of their colleagues. Following the suggestion of Kristin Jones, then Bellevue’s provost, Barge prepared a draft statement that Jones hoped would provide “context” about “what was approved by the Cabinet and why the sentence was removed.” Jones thought such a statement might be “helpful in calming the dialogue” on campus. (Jones has since ascended to become Bellevue’s acting president.)

Barge’s draft statement, prepared using research compiled by a staff member, argued:

A proposal was presented to the President’s Cabinet for the “Never Again is Now” art installation. That proposal was comprised of two sections: the image of the two children and the title. That proposal was approved for installation. The installation on display includes copy that was not proposed to and approved by the President’s Cabinet. Providing the full proposal to the President’s Cabinet would have enabled all parties to work together on the messaging related to the installation.

The additional section of the installation included information that was of concern from an overall accuracy and liability perspective. Based solely on these concerns, a sentence was removed. [...] [T]here is no evidence to support the belief that Freeman benefited from the relocation of Japanese Americans to internment camps during World War II. It was from a prominent white landowner that Freeman bought the 10 acres . . . . This is one of the primary areas of concern with the sentence that was removed along with potential liability for the College.”

But that statement was never sent. Instead, Barge sent a condensed version, stripping the explanation and leaving a “pure apology.”

But the un-sent, draft statement is revealing. Barge asserted that Bellevue acted out of concern for “potential liability” and “overall accuracy,” questioning how Miller Freeman could have financially benefited from buying land from a white landowner. But you can’t defame the dead, and it is facially inappropriate for a college administration to appoint itself the arbiter of the correct view of historical events. Never mind that the censored sentence didn’t assert that Freeman had financially benefited, just that he had been involved in “decades of anti-Japanese agitation” and that it impacted farmers in Bellevue.

Barge’s defense of Freeman’s legacy did not end there. In the early hours of the controversy, Barge wrote to Bellevue’s president, asking whether it would be possible as an “alternative” to “delete the name, keep the intent of the sentence and have that reinstalled?”

Following the initial mea culpas, Bellevue’s administration opted not to continue to engage with campus critics unsatisfied by Barge’s “courageous” apology. (Jones wrote to Barge, privately, that she was “dismayed at the responses to your apology. I’m guessing that nothing more you or we say will be enough for some people.”) But when the Seattle Times began making inquiries, the administration began working with a public relations outfit, and Barge cryptically suggested to the president’s assistant she had a string to pull: “I also received some inside information regarding sending a message to the owner of the paper regarding the story. It will not stop the story but will provide a heads up to him. He is a close personal friend of Kemper Freeman Jr.”

Less than an hour later, a Bellevue communications staffer had drafted two statements, one a “public statement” and the other apparently intended for an unidentified donor. The two statements:

“As an institution of higher learning, Bellevue College is committed not only to supporting our students, faculty and staff, but also to embracing, facing and exploring every aspect of our shared history.”

“As a longtime supporter of Bellevue College we wanted to make you aware that there may be a story in the Seattle Times regarding an incident that included the Kemper Freeman family. Please know that the College endeavored to strike an appropriate balance between our steadfast commitment to support our students, freedom of expression, and references to the Kemper Freeman family.”

It’s not clear for whom the latter statement was intended, or whether it was ever sent. But it is striking in its genuflection, characterizing an interest in “balance” between artistic expression about Japanese internment camps and criticism of a wealthy family.

And for what? Bellevue’s records reveal that Kemper Freeman, Jr. or his company had donated $14,750 to the college over the course of seven years. That, alone, might not be worth jettisoning any pretense of a commitment to expressive freedom. If it were, it would be staggering to think that at Bellevue, campus censorship could be bought (albeit indirectly) for about the same price as a used SUV from a local car dealership.

However, a demonstrable willingness to donate — modest in comparison to his contributions to civic and political campaigns — may have been an enticing lead to Bellevue’s leadership. The bulk of his contributions, a donation of $10,000, came in June, just months before the art installation. And other records produced to FIRE reveal the college’s president, who resigned in the fallout from the censorship scandal, asking to meet with Freeman and offering to make himself available in the “early morning for breakfast, after business hours or even on a Saturday if that would be more convenient.”

If a collegiate administration finds itself questioning whether to permit art or expression on campus in light of what it thinks might upset its donors, that’s a strong indication that its administrators should not be in a position to answer those questions.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

VICTORY: Court vindicates professor investigated for parodying university’s ‘land acknowledgment’ on syllabus

Can the government ban controversial public holiday displays?

DOJ plan to target ‘domestic terrorists’ risks chilling speech