Table of Contents

University of North Alabama censured over treatment of student newspaper adviser; unwritten media ‘protocol’ earns written letter from FIRE

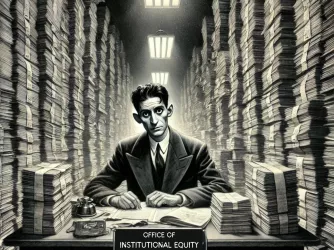

Yesterday, the College Media Association announced that its membership had voted to censure the University of North Alabama over its circumspect removal of a student newspaper adviser — a decision announced shortly after the university’s provost expressed displeasure over its media coverage. Today, FIRE is sending a letter to the university concerning a corollary threat to student journalists’ ability to speak to sources: an unwritten media “protocol” directing staff and faculty to ensure that statements to journalists have been “vetted” by administrators.

Inside Higher Ed provides the background:

The Flor-Ala newspaper ran a story in September about being denied personnel records of two employees, one of whom has resigned from the university. [That story is available here.] David Shields, former vice president of student affairs, left in July, and Gregory Gaston, a professor, is not allowed on the campus grounds.

A week after the story published, administrators met with student journalists and the newspaper’s adviser, Scott Morris, according to the association. Morris and the students characterized Provost Ross Alexander as “angry” and “frustrated.”

Later that month, Morris was told the provost would be eliminating his job and replacing it with a tenure-track faculty position that required a doctorate, which would result in Morris, a longtime journalist without the credential, being fired.

Anticipating the censure, the university sent a prepared email to its faculty and students claiming not only that the censure was “unwarranted,” but also that the CMA had acted “outside the scope of its authority.” Presumably, the university is professing concern over the CMA’s internal policies, which exclude from the investigating committee’s purview disputes arising from “personnel, budgetary, or other institutional actions based on policy” — as opposed to avowed instances of retaliation.

Perhaps the CMA — an organization dedicated to student media and their advisers — is a better authority on its own policies than the University of North Alabama. It’s not as if policy, budgets, and personnel decisions have never been used as a pretext to censorship. The CMA’s policy is clearly intended to cabin its mission to First Amendment issues, not personnel decisions wholly unconnected to freedom of the student press. This is not such a case.

Nor does the university find credible refuge in its substantive defense of its actions. The university’s position is that in “late 2014,” it had started “discussing an upgrade to the position of Student Media Advisor to a tenure track faculty position.” Yet the adviser now being rotated out was hired in September 2014. So even under the university’s theory, they hired an adviser at about the same time they planned to deprecate him and didn’t bother telling him until now. More likely, the purported personnel change is motivated — at least in part — by criticism from the student newspaper.

There are other reasons to be skeptical of the university’s response. The CMA reports that it provided the university with an opportunity to provide documentation to substantiate that its purported personnel change had been long-planned, but “administrators could provide absolutely no correspondence, reports or materials indicating they were thinking of changing this position before” the Flor-Ala article that sparked the provost’s discontent. More recently, the Flor-Ala reports, “the 2019 operating budget, which runs from Oct.1, 2018 to Sept. 30, 2019, did not change or reflect an upgrade within the department.”

That’s not the only concerning approach to journalists undertaken by the university in recent weeks.

As Inside Higher Ed reports:

The [College Media Association] said that administrators could not provide any proof that they were considering changing Morris’s position prior to the newspaper publishing its report. The university also sent out a reminder to professors and other staffers of the institution's rules, which suggest that officials should not speak to the media unless an administrator vets the inquiry beforehand.

That “reminder” extends not just to staff members of the university, but to faculty, as well. The Flor-Ala reported on the reminder about the media “protocol” in greater detail earlier this month:

The university administration issued a reminder to the UNA faculty and staff Oct. 25 about an in-house media protocol, which suggests faculty and staff do not speak to the media without the administration’s examination of all inquiries beforehand.

Director of Communications and Marketing Bryan Rachal said the protocol requires all media inquiries be sent through his office so the proper administrators can examine the faculty and staff members’ responses before releasing them to the media.

[ … ]

“The university asks that all employees follow the media protocol,” Rachal said. “This includes all faculty and staff. The university stands on its statement earlier in the week that it seeks to ensure that whatever is communicated to and through the media is accurate, clear and has been vetted by administrators who have the information and are responsible for the subject matter.”

Rachal said the university’s administration established the protocol in 2015, but there is no official documentation regarding it.

An unwritten, vague policy apparently directing staff and faculty to have their statements “vetted” by administrators is contrary to basic principles of the First Amendment. The chilling effect of such a directive will ultimately work to frustrate the efforts of student journalists while subordinating faculty members’ rights to administrators’ views on whether their statements are “accurate.”

Of course, UNA is hardly the first institution to create policies purporting to govern faculty interactions with journalists. This year, we’ve written to public colleges in Texas and New York about policies that required faculty to seek administrators’ approval before talking with the media. Those institutions at least put their policies in writing — and, importantly, changed them after FIRE pointed out how they imperiled First Amendment rights.

Today, FIRE sent a letter to UNA, pointing out that its unwritten policy chills the speech of faculty members and student journalists. We’re calling on the university to either abandon the policy or enshrine it in a written policy that conforms to the university’s obligations under the First Amendment. We’ve also issued a public records request asking the university to share instances of the unwritten policy’s use.

A public university should not be in the business of subjecting faculty comments on matters of public concern to the critical eye of administrators. That doesn’t demonstrate a healthy respect for the First Amendment. But if you want to ask faculty or staff whether UNA respects their First Amendment rights, make sure their response has been vetted by an administrator. It’s in the protocol, maybe.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

UPDATE: Another federal appeals court backs academic free speech for public employees

Feds to Columbia: ‘You want $400 million in contracts back? Do this (or else)’

A picture is worth a thousand words — unless a college district bans it