Table of Contents

Trump’s proposed constitutional amendment banning flag burning would have unintended consequences

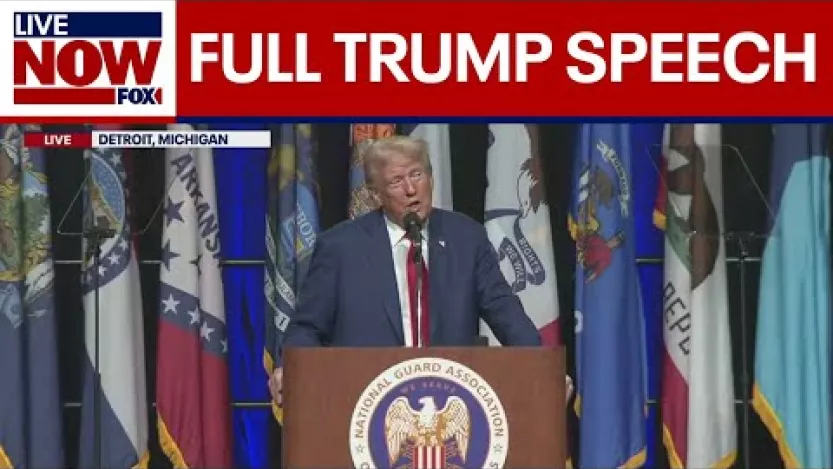

Ryan Garza / USA TODAY NETWORK

Former President Donald Trump at a campaign rally in Detroit, Michigan, on Monday, Aug. 26, 2024.

Of all the forms of free expression protected by the First Amendment, flag burning is one of the most contentious. Even though the Supreme Court ruled in 1989 that burning the American flag is a constitutionally protected form of free speech, many people, including presidential candidate Donald Trump, think it shouldn’t be.

On Monday, during a speech to the National Guard Association in Detroit, Michigan, the former president suggested that burning the flag should result in jail time.

“I want to get a law passed,” Trump said to the crowd at his campaign event, referencing recent protests in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention. “You burn an American flag, you go to jail for one year. We gotta do it.”

“They say, ‘Sir, that’s unconstitutional,’” he added. “We’ll make it constitutional.”

As the news media quickly pointed out, and as the Supreme Court ruled in Texas v. Johnson, burning the American flag is a form of expression protected under the First Amendment. And the Court later ruled in United States v. Eichman that a federal flag burning statute is unconstitutional.

Still, Trump’s comments raise the question: Could the Constitution be amended to permit the government to prohibit flag burning as a form of protest? And if so, how would a flag-burning amendment even work? Especially given broad protections for freedom of expression under the First Amendment?

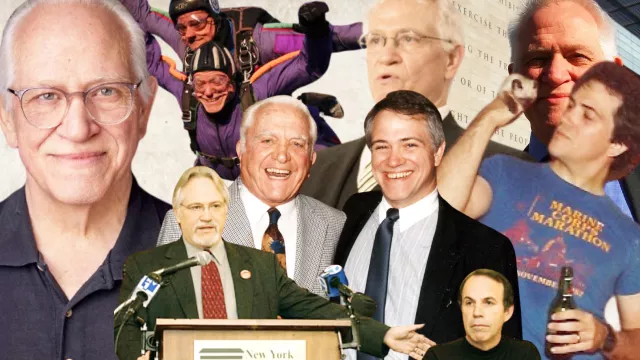

FIRE Chief Counsel Robert Corn-Revere explored this very scenario nearly 20 years ago in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks and subsequent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Ten questions to a media lawyer

News

Renowned First Amendment lawyer Robert Corn-Revere became interested in the First Amendment as a reporter for a local newspaper during the Watergate era.

At the time, a flag-desecration amendment appeared quite close to passing Congress with two-thirds majorities, after which it would go to state legislatures for approval. In a special issue of “First Reports,” a scholarly journal published by the First Amendment Center, Corn-Revere examines a hypothetical scenario in which such an amendment is adopted, explains how it might be interpreted by the courts, and outlines the probable impact of the amendment on freedom of speech.

“Passage of a constitutional amendment permitting Congress to ban flag desecration . . . would not end the ongoing debate about the limits of governmental authority in this area,” Corn-Revere wrote, adding that the Supreme Court decisions on flag desecration are part of an extensive legal history of symbolic speech. Even a constitutional amendment would not automatically erase that history.

“It will not be easy just to blot out those decisions with a constitutional amendment,” he said, “since any resulting law must conform to established norms of due process and First Amendment scrutiny.”

But for the sake of argument, let’s consider a hypothetical scenario in which a constitutional ban on flag desecration passes both chambers of Congress with two-thirds majorities and is then approved by three-fourths of state legislatures, making it the 28th amendment to the Constitution.

So, what would happen? Years of expensive litigation, varying and conflicting judicial interpretations, selective enforcement — oh, and more flag burning.

Far from solving the culture war over flag desecration, Corn-Revere predicted that a constitutional amendment would initiate new legal challenges and uncertainty as courts would likely offer conflicting interpretations of the amendment and apply the law unevenly.

“Instances of flag desecration for political purposes, at least in the short term, could increase dramatically,” he suggested, warning that arrests and lawsuits would almost certainly follow the passage of such an amendment.

The amendment could have a chilling effect on free expression, particularly in the short term, and would likely embolden efforts to restrict other forms of symbolic speech, leading to broader implications for civil liberties.

First, in the aftermath of the passage of the amendment and the subsequent protests and arrests for flag desecration, courts would be tasked with interpreting the amendment. Using previously proposed amendments as an example, Corn-Revere suggested that the terms “physical desecration” and “flag of the United States” are not as cut-and-dry as proponents of the ban might think. Using such broad terminology could lead to narrow interpretations that limit the amendment’s impact, allowing only a small number of prosecutions and leaving many acts of flag desecration unpunished, much to the dismay of the ban’s proponents.

“It is possible that the ultimate impact of a flag-protection amendment will deviate from the polarized extremes,” Corn-Revere suggested. “It could be that the amendment will be so sharply limited by constitutional interpretations that the law may be applied only in a minority of cases, thus providing broad opportunities for circumvention of its purpose by protesters.”

Second, the amendment could create significant legal uncertainty as courts at various levels of government struggle to determine the scope of the new law. This uncertainty could result in inconsistent rulings and a prolonged period of constitutional upheaval as courts work through the implications of the amendment.

Based on the long history of state laws against flag desecration and misuse, “this will likely produce a series of cases where the government seeks to apply the law to various items that appear to be flags, and to actions where the issue of ‘desecration’ is debatable,” Corn-Revere wrote. “History suggests that lower courts will issue conflicting decisions until the matter is finally presented to the Supreme Court in an appropriate case.”

Your burning questions on flag burning

Issue Pages

The right to burn the American flag sparks heated debate, but the First Amendment protects flag burning in most cases.

Third, Corn-Revere worried that the broad phrasing of the amendment would lead to discriminatory or selective enforcement. Prosecutors might target certain individuals or groups based on their political views or the nature of their protest, leading to further controversies and legal challenges.

Enacting a constitutional amendment banning flag desecration “would permit the government to impose heightened penalties for instances of flag destruction even if certain acts are already illegal under other criminal laws. However, the ability to assess heightened penalties has a dark side,” Corn-Revere warned, and using police arrest data suggests that arrests could follow a common pattern, where a person is arrested and spends one or more days in jail only to see the charges eventually dropped.

As Corn-Revere observed, research “suggests that a new flag desecration law could give law enforcement more arbitrary discretion to permit only that expression which local officials will tolerate.”

Lastly — and perhaps most importantly — proponents argue that a constitutional ban on flag desecration would not broadly undermine First Amendment values, but Corn-Revere suggested otherwise. The amendment could have a chilling effect on free expression, particularly in the short term, and would likely embolden efforts to restrict other forms of symbolic speech, leading to broader implications for civil liberties.

The issues raised then are no different than what we would face under candidate Trump’s current proposal. As Corn-Revere notes: “Trump’s proposed ban on flag burning is nothing new, and it would not reduce dissent. To the contrary, adopting a constitutional amendment would only spark more instances of flag burning, and would lead to a long series of disputes over flag desecration.”

Read “Implementing a Flag-Desecration Amendment to the U.S. Constitution” (July 2005) by FIRE Chief Counsel Robert Corn-Revere

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

FIRE statement on immigration judge’s ruling that deportation of Mahmoud Khalil can proceed

FIRE comment to FCC calls for review of regulations that may violate the First Amendment

FIRE welcomes Allison Hayward to board of directors