Table of Contents

Thinking about a Student Bill of Rights?

On Friday, The Brandeis Hoot reported that the Brandeis Student Union is going to spend next semester working on a Student Bill of Rights. Every private college is different, more or less, so I would hesitate to give specific advice to students who want to craft such a document at their college. But since December 15 is Bill of Rights Day, let me provide some principles and questions for students to consider:

1. Do you actually need a “Bill of Rights”? Recall that the United States Constitution did not originally include one. A main argument against enumerating rights was that by naming some rights, other rights would be neglected or insufficiently protected. But by 1791, that argument had lost, and the U.S. Bill of Rights is now part of the Constitution. Still, we should not forget that rights such as the right to freedom of speech are moral rights, human rights, not just legal rights. If your Student Bill of Rights fails to enumerate certain rights, will an administrator try to tell you that those rights do not exist?

2. Read your Student Handbook or Student Code of Conduct. Take note of how your college already identifies student rights. The issues involved here are not simple. State and federal laws, not to mention court precedents, affect student rights on a wide variety of issues, including release of educational records and other personal information, harassment policies, and so on. Are you prepared to ask your college to adopt a completely new document written by students, in place of their own documents? Or are you offering a supplemental list of rights only?

3. Consider the politics of asking your school to adopt your statement of rights—whether or not the statement enjoys widespread support among students and the student government. Given the current climate on campus, will this move be taken as cooperative or antagonistic? Would you be able to do more good by offering specific additions or changes of wording in existing college documents, rather than something entirely new?

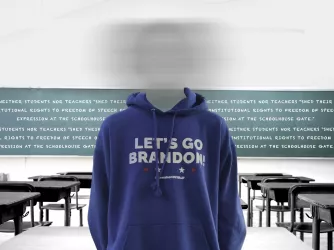

4. Consider the case of California, where private colleges and universities are required to uphold the same speech rights that students enjoy at public universities. If you persuaded your college to offer you the same speech rights enjoyed by the students at the public university down the street, it would be a victory for free speech. That victory would not be a defeat for “civility,” just a promise that the college will no longer be the policeman of offensive speech. As I wrote recently, students are quite able to punish or defeat such speech on their own through social pressure and the marketplace of ideas—which often are more effective mechanisms anyway.

5. If you are not sure where to start, try checking out your school’s rating in our just-released Spotlight on Speech Codes 2007: The State of Free Speech on Our Nation’s Campuses (if your school is among the over 345 schools listed). Together with FIRE’s detailed listings on Spotlight, which records the relevant policies at each school, this report will help you see why your school earns a “red light,” “yellow light,” or “green light” for its policies regarding free speech. This is just a start. What about due process, freedom of conscience, religious liberty, freedom of assembly, academic freedom, the student right to know when an academic issue is deeply contested (as even the American Association of University Professors suggests), and so on? Again, these are not just legal matters but moral matters for anyone who takes human rights seriously. That should be a main reason why you are considering a “Bill of Rights” at your college in the first place.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

Supreme Court must halt unprecedented TikTok ban to allow review, FIRE argues in new brief to high court

Australia blocks social media for teens while UK mulls blasphemy ban

Media on the run: A sign of things to come in Trump times? — First Amendment News 451