Table of Contents

On Student Press Freedom Day, a look back at censorship in 2018

Despite what you may have heard in school, America is (by some measures) not home to the freest press in the world. Since 2013, the United States’ press freedom ranking tumbled 13 spots to 45th globally.

And freedom of the press is even more attenuated for student reporters, who face additional hurdles from administrators, legislators, and even fellow students. Today, FIRE is joining the Student Press Law Center to highlight Student Press Freedom Day by taking a look at the biggest student press freedom issues from last year, and suggesting ways you can help protect student media from censorship.

In conjunction with the Freedom Forum Institute and the Newseum, the SPLC announced 2019 as the Year of the Student Journalist. Goals of the initiative include raising awareness of student journalists’ valuable work, highlighting censorship challenges, and showcasing the contribution student media makes to civic life.

Get Involved: Use the hashtag #StudentPressFreedom on social media to highlight the importance of a free press.

Newspaper-nappers

Among the boldest forms of student press censorship is newspaper theft.

The first newspaper-napping tracked by the SPLC in 2018 happened at Kansas’ Butler Community College one year ago tomorrow, when nearly a third of The Lantern’s 1,400 newspapers were stolen from their racks. Student representatives for the newspaper said they believed the papers were stolen due to the Jan. 31 edition’s front page story about a former BCC football player being charged with murder.

Evidence from a surveillance camera caught a student destroying the newspapers, and another student admitted to discarding them because he was angry over the paper’s coverage of the arrest. But university police discounted the crime, telling the student newspaper, “I know it is a form of censorship, but criminally there is really not much to look at.”

Frank LoMonte, SPLC senior legal fellow disagreed: “If I go into the Salvation Army soup kitchen, and instead of taking one bowl of soup, I grab the entire kettle of soup and pour it down the sewer drain, I’ve definitely stolen property.”

In April, another newspaper-napping happened at Tennessee Tech University, when a student admitted to stealing 800 newspapers to make a paper mache music note to place on his former high school marching band’s parade float. (At least that one wasn’t over content.) And in September, yet another thief made off with 450 copies of the University of Oklahoma student newspaper, The OU Daily. The front page article when the papers were stolen detailed an OU drama professor under investigation for sexual harassment.

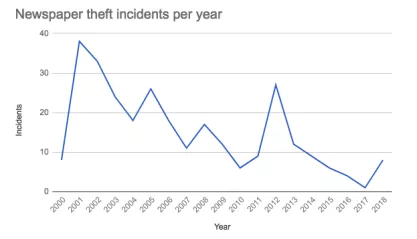

The SPLC tracks student newspaper theft. In 2018, they tallied eight such incidents, the highest number since 2014. In 2017, the group only recorded one instance.

The SPLC estimates that student media outlets lose thousands of dollars a year due to theft. And should university police seem hesitant to respond, the organization has compiled a list of successful newspaper theft prosecutions where thieves were fined, given probation, and/or charged with criminal mischief, so those that something can be done about such thefts.

Cutting budgets

Another way college authorities can censor students is by cutting their budgets. Last March, the student government of Wichita State University approved a budget that reduced the funding of the school newspaper by $25,000. A month later, the University of Mary Washington’s student government slashed the school newspaper’s budget from over $13,000 to $100. After criticism, the funding was fully restored the following month. And in Illinois, Lindenwood University administrators moved the student magazine to an all-digital format. Administrators cited budgetary concerns: the magazine was printed 2-3 times a semester at a cost of between $4,000 and $6,000. Student editors, however, said that removing the printed copies from campus was “a weak cover-up and a blatant attempt at censorship.”

Newspapers that are not independent are at the mercy of universities’ budgets, and criticism of the school — as justified as it may be — can cause leaders to take a harsher look at how much funding they allocate to university publications.

The problem has become so severe that the staff of The Alligator at the University of Florida launched a campaign to highlight the problem. Save Student Newsrooms aims to shine a light on the unique challenges facing student-run newsrooms. The group wrote that “student-run media organizations need to start calling attention to the challenges we face, as many of us fight to maintain financial independence and an increasing number of us now face concerns of editorial independence under university administrations.”

The Flor-Ala fiasco

Recent events at the University of North Alabama illustrates what happens when the most censorious impulses of college administrators go unchecked.

In November, the College Media Association censured UNA, signaling its strongest condemnation for UNA’s retaliatory removal of the faculty adviser for the school’s student newspaper, The Flor-Ala. The provost had openly objected to paper’s unflattering coverage of the school, just before changing the adviser’s job description to require a Ph.D., which just happened to mean that the existing adviser would have to leave at the end of the academic year.

FIRE responded with two letters: One echoing CMA’s concerns over the adviser’s firing, and a second on a related media policy, which directed faculty and staff to get all correspondence with media “vetted” by administrators. Such a policy — known as a prior restraint — is contrary to basic First Amendment principles by limiting coverage to what administrators deem worthy of publication. UNA staff members were “reminded” of the policy the same week the adviser’s job was changed.

To date, the university has not justified its policy or made attempts to give its faculty members the expressive rights that would allow student journalists at The Flor-Ala to do their jobs. Today, FIRE sent UNA another letter urging the school to stop its pattern of retaliatory censorship against the Flor-Ala and to reinstate the existing adviser position. FIRE will continue to monitor the situation and keep Newsdesk readers updated.

More censorship at Christian colleges?

A study last year suggested that students at Christian colleges, which frequently place religious values over press freedom, do face more press censorship attempts.

In April, students at Indiana’s Taylor University surveyed newspaper staffs at Christian colleges all over the country to see if others faced the same type of censorship they felt from administrators. Less than a quarter of respondents said that their school gives them the same press freedoms that they would have at public universities. Fully 76 percent said they faced pressure from their university to edit or remove an article after publication.

As FIRE has long noted, students at private schools should carefully read their schools’ policies on freedom of expression. Many of these schools are within their rights to place other values over a free press or freedom of speech, but some have contradictory policies that may suggest their students can also count on First Amendment-like freedoms, when in fact, they cannot. For example, Taylor University itself highlights its dedication to truth and “encourages students to ask hard questions, apply themselves to the tasks at hand, and embrace their callings.” This should include students whose calling is to service through journalism.

Where’s the liberty at Liberty?

In August, FIRE wrote to another Christian college, Liberty University, over administrative meddling in editorial decisions in the student newspaper. In FIRE’s letter to college president Jerry Falwell Jr., we noted that Liberty’s actions conflicted with his own assertion that it “promotes the free expression of ideas unlike many major universities where political correctness prevents conservative students from speaking out.”

WORLD — a magazine which reports from a Christian perspective — wrote a piece detailing how the newspaper at Liberty functioned more as the public relations arm of the university than a journalistic outlet. According to WORLD, stories were nixed if they were critical of Liberty or Falwell’s friend, President Donald Trump. Student journalists had to maneuver through a two- or three-tier approval process, sometimes waiting for Falwell himself to decide whether a story was suitable for publication. According to WORLD, he even required student editors to end op-eds with a note on who they supported for president.

WORLD also reported that Bruce Kirk, dean of the communications school, went so far as to tell newspaper staff members:

Your job is to keep the LU reputation and the image as it is. … Don’t destroy the image of LU. Pretty simple. OK? Well you might say, ‘Well, that’s not my job, my job is to do journalism. My job is to be First Amendment. My job is to go out and dig and investigate, and I should do anything I want to do because I’m a journalist.’ So let’s get that notion out of your head. OK?”

This is egregious behavior for anyone who professes to be overseeing actual news reporting. And it’s particularly ironic coming from a school with the gall to call itself Liberty.

More than five months later, FIRE is still awaiting a reply to our letter.

New Voices legislation

Free speech advocates, including FIRE, have been advocating for New Voices legislation to protect student press rights. The New Voices Act is three-tiered legislation that states can adopt to restore, protect, and extend student expression rights in K-12 and college.

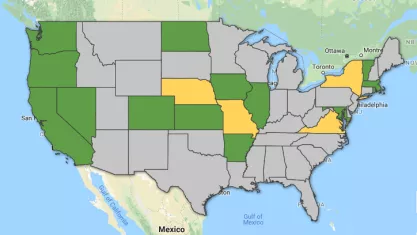

The main concerns stem from 1988’s Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, the U.S. Supreme Court ruling allowing grade school administrators to censor school-sponsored publications for “legitimate pedagogical reasons.” In 2005, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit extended that prior review control to college administrators overseeing campus publications. New Voices legislations aims to prevent this decision from spreading outside the Seventh Circuit, which is made up of Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin.

Fourteen states have passed New Voices legislation in whole or in part: Arkansas, California, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington.

On Monday, a legislative panel in Virginia rejected a bill that would have protected student journalists from administrative censorship unless the content was libelous, slanderous, unjustifiably invaded privacy, violated federal or state law, or incited a clear and present danger. If it had passed, Virginia would have been the 15th state to adopt New Voices legislation. Similar bills have been introduced this year in Hawaii, Missouri, Nebraska, New York.

To get involved in your state, check out New Voices’ interactive map. The initiative, a project of the SPLC, can help you connect with supporters in your state.

Looking ahead: Censorship in 2019

Just last week, at Dixie State University — no stranger to criticism from FIRE — student reporters asked the state’s attorney general to enforce Utah’s public meetings law, alleging DSU was denying them access to faculty senate and student government meetings. According to The Salt Lake City Tribune, the student editor “compared reporting on campus goings-on to climbing a wall, saying sources have been reluctant to speak with her and other student journalists, have ignored the paper’s requests for public university records, and have blocked access to meetings.”

The university is digging in its heels, claiming that the public meetings law doesn’t apply to the meetings in question. But according to the Tribune, the student staff of the Dixie Sun News and their attorney are arguing that meetings of advisory boards for government entities, such as public universities, should be open to the public and members of the press.

Students shouldn’t have to seek the help of an attorney to attend meetings at a public university. FIRE agrees with the Sun News staff.

How can I help?

Stay tuned to Newsdesk for additional cases of student press censorship throughout the year. Share your thoughts on social media with the hashtag #StudentPressFreedom, and subscribe to FIRE Updates and the SPLC newsletter for breaking news.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

FIRE's 2025 impact in court, on campus, and in our culture

The trouble with banning Fizz

VICTORY: Court vindicates professor investigated for parodying university’s ‘land acknowledgment’ on syllabus