Table of Contents

The State of Free Speech on Campus: Washington University in St. Louis

Throughout the spring semester, FIRE is drawing special attention to the state of free speech at America's top 25 national universities (as ranked by U.S. News & World Report). Today we review policies at Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL), which FIRE has given a red-light rating for maintaining policies that clearly and substantially restrict free expression on campus.

As a private university, WUSTL is free to place other values above the right to free expression—but it must do so openly, in such a way that any prospective student or faculty member considering joining the university community would be aware that they would be giving up their fundamental rights in exchange for doing so. To the contrary, WUSTL's policies and statements repeatedly emphasize the importance of free speech and expression to the university's mission, creating the impression that free speech is not only protected but highly valued at the university. The university's Student Judicial Code, for example, provides that "Freedom of thought and expression is essential to the University's academic mission." The Policy Statement on Demonstrations and Disruption states that

In pursuit of its mission to promote teaching and learning, Washington University in St. Louis encourages students, faculty and staff to be bold, independent, and creative thinkers. Fundamental to this process is the creation of an environment that respects the rights of all members of the University community to explore and to discuss questions which interest them, to express opinions and debate issues energetically and publicly, and to demonstrate their concern by orderly means.

And the university's Discriminatory Harassment Policy includes the following provision:

In an academic community, the free and open exchange of ideas and viewpoints reflected in the concept of academic freedom may sometimes prove distasteful, disturbing or offensive to some. Indeed, the examination and challenging of assumptions, beliefs or viewpoints that is intrinsic to education may sometimes be disturbing to the individual.

Despite all of these strongly worded commitments to free speech—even controversial and offensive speech—some of WUSTL's policies place severe limitations on students' right to open expression. In particular, the policies maintained by the university's Residential Life office contain numerous free speech violations. This is a common problem FIRE sees in the administration of university policies: while official university-wide policies may have gone through extensive review and been approved by the university's legal department, other departments maintain their own policy manuals with policies that may have not undergone such an extensive vetting process. The result is restrictive policies that curtail free speech in specific areas such as university housing or in student activities, even on campuses where the university's overarching policies are appropriately protective of free speech.

Here, for example, while the university-wide harassment policies are generally reasonable and come close to tracking the appropriate legal standard for harassment, the Office of Residential Life harassment policy provides that

Harassment is defined as any behavior or conduct that is injurious, or potentially injurious to a person's physical, emotional, or psychological well-being, as determined by the sole discretion of the University. (Emphasis added.)

There are several serious problems with this policy. First is the fact that this definition of harassment bears no relationship to the legal definition of harassment in the educational context. To constitute unprotected harassment in the educational context, conduct must be "severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive." Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, 526 U.S. 629 (1999). This policy contains absolutely no requirement of severity or pervasiveness; in fact, it does not even require that the conduct be "injurious"—conduct that the university deems "potentially injurious" will suffice, whether or not there was any actual injury! What's more, the definition of what constitutes an "injury"—harm to someone's "emotional well-being"—is so vague that no student can possibly know what is prohibited. Is it only conduct that causes severe emotional distress of the sort that would interfere with someone's educational opportunities enough to constitute actual harassment? Or do mere hurt feelings suffice? Finally, the fact that what constitutes harassment is left to "the sole discretion of the University" both renders the policy hopelessly vague (how can students know what is prohibited when the university has sole discretion to decide on a case-by-case basis?) and virtually guarantees inconsistent enforcement and double standards.

Residential Life's Posting Guidelines also contain impermissible content-based restrictions on students' right to free speech. Those guidelines provide that

No reference to alcohol, drugs, or nudity is permissible; no sexist or discriminatory materials allowed. What constitutes sexist or discriminatory materials will be left to the discretion of the Residential Life staff.

As with the residential life harassment policy, there are several problems with this policy. As an initial matter, while the university may regulate posters that explicitly promote illegal activity (such as a poster inviting underage students to drink at a party or a poster advertising illegal drugs for sale), it may not prohibit a student group from advertising, for example, a debate about marijuana legalization or an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. Concern over abuse of a policy like this is more than theoretical; several years ago, Colorado State University maintained a similar policy prohibiting "any reference to alcoholic beverages or drugs" in the residence halls, and that policy was used to prohibit the Campus Libertarians from posting flyers advocating for a Colorado drug reform ballot initiative because the flyers contained an image of a marijuana leaf. Colorado State has since revised its policy to require only that advertisements not "promote illegal behavior," and WUSTL should do the same.

The prohibition on "sexist" or "discriminatory" materials is equally problematic, because those terms are undefined and their meaning is explicitly "left to the discretion of the Residential Life staff." The staff could easily use that discretion to decide, for example, that a flyer advertising an anti-illegal-immigration speaker is "discriminatory" or that a womens' center flyer advertising V-Day events is "sexist." Moreover, even most expression that truly is "sexist" and even "discriminatory" (except to the extent the expression actually constitutes discrimination, such as an advertisement for an event whose audience is illegally restricted to people of only one race or gender) is protected by the right to free speech.

Yet another problematic policy comes from WUSTL's Residential Life office, and that is the policy on responding to so-called "hate incidents." A hate incident is defined, broadly, as "an incident where the perpetrator engages in harmful actions based on prejudices and biases." Specific examples of hate incidents include "name calling" and "jokes." Like so many university hate and bias incident policies and protocols, WUSTL's policy does not specify whether bias incidents alone can form the basis for disciplinary action. However, it explicitly states that "the victim does have the choice to pursue the judicial process related to the incident." Given that WUSTL's definition of a "hate incident" includes protected speech (jokes and name calling, unless they rise far beyond causing mere offense, are protected), this means that protected speech is subject to investigation on WUSTL's campus. This, in and of itself, is enough to chill free speech on campus, since students will almost certainly wish to avoid the negative educational effects that would result from being subjected to any sort of disciplinary investigation, keeping silent about matters that ought to be freely discussed on a college campus.

To a lesser extent, WUSTL's Computer Use Policy is also problematic. That policy provides that

Electronic mail should adhere to the same standards of conduct as any other form of mail. Respect others you contact electronically by avoiding distasteful, inflammatory, harassing or otherwise unacceptable comments. (In an academic community, the free and open exchange of ideas and viewpoints preserved by the concept of academic freedom may sometimes prove distasteful, disturbing or offensive to some. This policy is not intended to restrict such exchange.)

It may be that this language exists only to encourage students to keep electronic communications respectful, but because of its location in a document explicitly designated as a "policy," it would not be unreasonable for students to assume that "distasteful" or "inflammatory" electronic expression might be cause for discipline or at least investigation. If this portion of the policy is truly aspirational—as I suspect it is—its aspirational nature needs to be stated more clearly so as to avoid a "chilling effect" on campus speech caused by students' reasonable misunderstanding of the policy.

Washington University in St. Louis has a moral obligation to uphold the promises of free speech it makes to its students and faculty. To do so, it must immediately revise its restrictive policies in order to open its campus to free expression.

Stay tuned next week for information on the state of free speech at Northwestern University.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

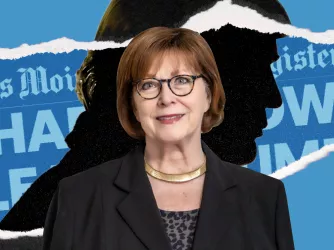

FIRE’s defense of pollster J. Ann Selzer against Donald Trump’s lawsuit is First Amendment 101

China’s censorship goes global — from secret police stations to video games

High schoolers: Become a voice for tomorrow, today!