Table of Contents

Stanford Law faculty, dean come to defense of student, call for systemic reforms

Michael Warwick / Shutterstock.com

In the wake of last week’s volcanic public response to an investigation initiated by Stanford University’s Office of Community Standards — the university agency tasked with enforcing student conduct regulations — Stanford Law’s faculty and dean have issued laudable statements defending students’ expressive rights.

Nicholas Wallace’s email satirizing the Stanford Federalist Society first drew a formal complaint from officers of the group, who told the Office of Community Standards on March 25 that the pasquinade “defamed” the group and two elected officials. The investigation that followed sparked a vociferous response on Twitter, leading Stanford administrators to quickly back down.

Stanford University’s retreat was soon followed by an email from Jenny S. Martinez, Dean of Stanford Law School, who noted that the investigation was not initiated or approved of by the law school. Citing her work defending freedom of expression, Dean Martinez condemned the investigation’s chilling effect:

Stanford Law School is strongly committed to free speech, is concerned about actions and climate that have the potential to chill speech, and has shared these concerns with the University. When I became aware of this particular situation, I strongly urged the University to consider whether it needs procedures that more quickly resolve whether constitutionally protected speech is involved in a Fundamental Standard complaint, and also the policies and procedures that led to their placing a graduation hold on this student on the eve of final exams.

[ . . . ]

I also want to say how upsetting this is to me personally. A commitment to First Amendment rights is part of why I became a lawyer. My first experience with the law was as a high school student when my high school censored the school yearbook and as a mock trial student, I started a protest in support of the speech rights of the yearbook (and had my pamphlets on the First Amendment confiscated by the vice principal). In college, as a student journalist, I worked for a summer at the Student Press Law Center defending the free speech rights of students. And through my service on the board of an NGO, I spent substantial time over the past decade working on freedom of expression issues globally. It is crystal clear to me that, as the university concluded yesterday, the satirical flyer is constitutionally protected speech.

I have received many requests this year to condemn, punish, or otherwise suppress speech, from all sides of the political spectrum. I want to reiterate that I will not be entertaining any such requests. Experience shows us the costs of policing speech are too high, and that vigorous and open debate of ideas is essential to a free society. While I urge thoughtfulness as people choose how to exercise their First Amendment rights in a community dedicated to learning, ultimately individuals must be guaranteed a broad range of freedoms to decide what their conscience and values dictate.

Dean Martinez’s condemnation was echoed by an open letter signed by faculty members from across the ideological spectrum, calling for an explanation from the university. They wrote, in part:

The e-mail was clearly satirical in nature and addressed a matter of urgent public concern, namely the January 6 riot in Washington, D.C. Accordingly, any threat of punitive sanction should have been quickly rejected as inconsistent with the university’s established policies and its legal obligations under California’s Leonard Law. We are embarrassed and angered that, instead, the Office of Community Standards initiated an investigation and placed a hold on Wallace’s graduation. These actions are antithetical to the values this law school holds.

Although the university reversed its decision after national media attention, we are concerned about the effects on Wallace and on student culture more generally. Incidents such as these have caused serious distrust among our students, who fear that our commitment to free speech is selective, and determined by power rather than principle. We seek an explanation for how the decision in this most recent case was made.

Stanford University’s administration owes that explanation, at least, to Wallace and to its faculty.

To its students, it owes more. Dean Martinez is quite right to point out that the decision to investigate Wallace was the choice of an administrative body — the Office of Community Standards — not controlled by Stanford Law School. But because the failings here lay at the doorstep of the office responsible for adjudicating codes of conduct for students across the university, the rights of all Stanford students (not just law students) are jeopardized by policy failures.

Both open letters called on Stanford University to take steps to prevent this from happening again — institutional reforms that will benefit more than just Stanford Law students. Dean Martinez wrote:

I think it is imperative that we take action to ensure that something like this does not happen again and will be working with faculty colleagues at the law school and around the university to do that.

Likewise, the faculty letter urges the university to “work to eliminate perceptions of bias in its treatment of different kinds of speech and to collaborate with the faculty to develop clear and consistent principles that will govern its approach when similar issues arise.”

Those calls should be taken seriously and taken up expeditiously by Stanford University’s administration.

What might those reforms look like?

Allegations of student or faculty misconduct which involve expressive activity should receive a threshold review before a formal investigation is opened into a student or faculty member. Allegations that do not plausibly suggest unprotected expression must be summarily rejected and no further investigation conducted or charges brought.

If an institution cannot ascertain for itself whether speech is protected, it should not initiate or announce an investigation, which itself will create a chilling effect even if the student or faculty member is ultimately vindicated.

A threshold review must:

- Analyze and conclude whether, accepting the complainant’s allegations as true, the speech would be unprotected under First Amendment principles. If the alleged violation involves both protected speech and speech or conduct that is not protected, the finding should specifically identify any speech that is protected.

- Be conducted by an administrator trained in the principles of expressive rights; and

- Be set forth in writing and a copy given to the student or faculty member at the outset of any investigation.

While there may be instances in which it is not reasonably possible to undertake such a review (such as when a student makes a true threat of violence), such a review should be done whenever circumstances allow or as soon as reasonably practicable.

A threshold review would give breathing space to student and faculty speech. An investigation can not only immediately chill student and faculty expression, but can have long-lasting effects for students who intend to go on to careers requiring background checks. If an institution cannot ascertain for itself whether speech is protected, it should not initiate or announce an investigation, which itself will create a chilling effect even if the student or faculty member is ultimately vindicated.

Stanford should not be alone in establishing these procedures. These types of investigations are a regular occurrence at many institutions, each of which is one satirical email away from following in Stanford’s footsteps.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

Trump administration’s reasons for detaining Mahmoud Khalil threaten free speech

VICTORY! 9th Circuit rules in favor of professor punished for criticizing college for lowering academic standards

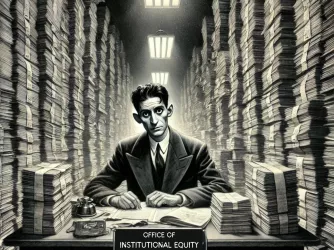

Navigating the Kafkaesque nightmare of Columbia's Office of Institutional Equity