Table of Contents

In Ruling with Nationwide Significance, Second Circuit Vacates ‘Doe v. Columbia’ Decision

Today, in a ruling of nationwide importance, a federal appellate court gave a Columbia University student suspended for sexual misconduct a new shot at proving that the university denied him a fundamentally fair proceeding.

While many students have sought to challenge the unfair processes that universities often use to adjudicate claims of sexual assault, such claims—while morally compelling—do not always fit neatly into a legal framework. This is particularly true at private universities, where there is no constitutional right to due process. Without the option of a constitutional claim, many students challenging private university procedures have argued that universities are violating Title IX by discriminating on the basis of sex in their handling of sexual misconduct claims.

As I wrote about earlier this week, a number of courts have dismissed these Title IX claims in the early stages of litigation, applying a strict interpretation of federal pleading standards—the requirements a plaintiff’s complaint must meet in order to set forth a plausible claim for judicial relief in federal court. One of the earliest high-profile decisions to dismiss an accused student’s claim on these grounds was the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York’s April 2015 ruling in Doe v. Columbia University.

In that case, the plaintiff—who is proceeding under the pseudonym John Doe—alleged that the procedures Columbia used to adjudicate his case were adopted in response to complaints that “the school is not being firm enough in the disciplinary process on cases involving alleged sexual misconduct by female students against male students at Columbia University.” The district court dismissed the complaint, ruling that Doe’s allegations of sex discrimination were too conclusory under the pleading standards established by the Supreme Court of the United States.

The district court also ruled that Doe’s allegations that Columbia had demonstrated bias against accused students did not support an inference of gender bias. It held that a bias against accused students could just as easily be

prompted by lawful, independent goals, such as a desire (enhanced, perhaps, by the fear of negative publicity or Title IX liability to the victims of sexual assault) to take allegations of rape on campus seriously and to treat complainants with a high degree of sensitivity.

As one of the first major rulings in a new crop of lawsuits stemming from universities’ sexual misconduct adjudication processes, the district court’s decision had an immediate and nationwide impact. It was quickly cited by a number of other judges dismissing students’ complaints on pleading grounds, impacting cases against the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Case Western Reserve University, and the University of Missouri.

Today, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed that decision, sending the case back to the district court for further proceedings. The Second Circuit’s ruling was based in part on an intervening Second Circuit decision—Littlejohn v. City of New York—that clarifies the pleading standards for discrimination claims in the Second Circuit. Although that rationale is not binding on courts in other jurisdictions (the Second Circuit includes Connecticut, New York, and Vermont), it may prove persuasive, particularly as judges have recently started to take greater notice of the nationwide context in which these cases are arising.

More importantly in my view, however, the Second Circuit expressed deep skepticism about the lower court’s view that a university’s alleged bias against accused students could be regarded as wholly distinct from an alleged bias against male students. On that issue, the court wrote:

It is worth noting furthermore that the possible motivations mentioned by the district court as more plausible than sex discrimination, including a fear of negative publicity or of Title IX liability, are not necessarily, as the district court characterized them, lawful motivations distinct from sex bias. A defendant is not excused from liability for discrimination because the discriminatory motivation does not result from a discriminatory heart, but rather from a desire to avoid practical disadvantages that might result from unbiased action. A covered university that adopts, even temporarily, a policy of bias favoring one sex over the other in a disciplinary dispute, doing so in order to avoid liability or bad publicity, has practiced sex discrimination, notwithstanding that the motive for the discrimination did not come from ingrained or permanent bias against that particular sex.

I had always been particularly troubled by that portion of the district court’s ruling, so I was gratified to see the Second Circuit address it here.

Going forward, it will be interesting to see what the impact of the Second Circuit’s decision is, both on the Doe v. Columbia case—because many cases have settled following the denial of a motion to dismiss—and on cases nationwide, many of which still have motions to dismiss pending. We’ll keep you posted.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

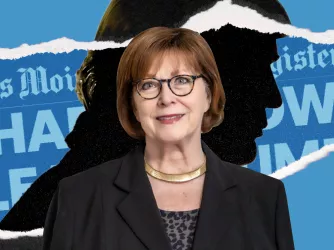

FIRE to defend veteran pollster J. Ann Selzer in Trump lawsuit over outlier election poll

FIRE’s defense of pollster J. Ann Selzer against Donald Trump’s lawsuit is First Amendment 101

A decade after ‘Charlie Hebdo’ killings, we are still failing blasphemers