Table of Contents

Purdue University Calumet Declares Professor Guilty of 'Retaliation'

As we wrote here a few weeks ago, Purdue University Calumet (PUC) professor Maurice Eisenstein was recently the subject of a months-long harassment investigation based on charged remarks about Islam he made on his personal Facebook page and while teaching. A number of students, calling the remarks offensive, submitted complaints to PUC.

But merely causing offense, even serious offense, does not constitute harassment in the educational setting. Indeed, speech has to be more than simply "offensive" to lose First Amendment protection and become actionable harassment. This is why we were glad that, following a letter from FIRE, PUC dismissed all nine harassment claims that had been filed against Eisenstein, even though it took far too long for the university to do so.

Unfortunately, the saga isn't over for Eisenstein. While PUC threw out the harassment claims against him, it still found him guilty on two charges of "retaliation" for remarks he allegedly made during the course of the investigation to two of his faculty colleagues who had filed complaints. The substance of the comments at issue is as follows, as described in our March 5 letter to PUC:

First, a professor accused Eisenstein of retaliation for the following interaction, as described in the relevant decision letter of February 22 to Eisenstein:

[The professor] reported that she said, "Hi" to Dr. Eisenstein, and that he responded, "Now I know why your son committed suicide."

Eisenstein denies making such a comment. However, in your letter, you explained that you "find it more likely than not that this incident did occur, and that it was retaliation for [the professor] having filed a complaint against Dr. Eisenstein," and that as a result, PUC will issue "a formal written reprimand to Dr. Eisenstein."

Second, another professor accused Eisenstein of retaliation for the following interaction, as described in the relevant decision letter of February 22 to Eisenstein:

[Eisenstein] sent an electronic communication to two colleagues associated with the Jewish Federation that read:

"There will not be anything from [the professor] sent to anyone in this house. My mother cursed him before her death (a true Orthodox curse.) He knows why. Therefore, there will be no association with him period. I consider anything from him to be in and of itself cursed and therefore untouchable. In respect for my mother z'l, I and my family will also consider him in a like manner."

Eisenstein notes that this response was sent from his personal email account and followed an unsolicited email sent to Eisenstein's personal account from the professor. In your letter, you explained that you "find that Dr. Eisenstein sent this email in retaliation for [the professor's] initial complaint."

A written reprimand was placed in Eisenstein's file for each charge.

The problem here is that, like the dismissed harassment claims, the alleged instances of "retaliation" in question-both of which consisted of a single expression or encounter, one of which Eisenstein denies even took place-constitute protected speech, and fall far short of the Supreme Court's articulation of what kind of conduct and/or expression constitutes workplace retaliation. FIRE explained this to PUC Chancellor Thomas L. Keon in our March 5 letter:

In Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway v. White, 548 U.S. 53, 67 (2006), the Court found that [the Civil Rights Act of 1964's] Title VII's "antiretaliation provision protects an individual not from all retaliation, but from retaliation that produces an injury or harm." Specifically, the Court determined that alleged retaliation must be "materially adverse," meaning that the retaliation would have "dissuaded a reasonable worker from making or supporting a charge of discrimination." Id. at 68 (internal quotation and citations omitted).

While this standard is seemingly broad, the Court made clear in Burlington Northern that Section 704(a) requires "material adversity because we believe it is important to separate significant from trivial harms."Id. (emphasis in original). The Court wrote:

Title VII, we have said, does not set forth "a general civility code for the American workplace."Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc., 523 U.S. 75, 80, 118 S. Ct. 998, 140 L. Ed. 2d 201 (1998); see Faragher, 524 U.S., at 788, 118 S. Ct. 2275, 141 L. Ed. 2d 662 (judicial standards for sexual harassment must "filter out complaints attacking ‘the ordinary tribulations of the workplace, such as the sporadic use of abusive language, gender-related jokes, and occasional teasing'"). An employee's decision to report discriminatory behavior cannot immunize that employee from those petty slights or minor annoyances that often take place at work and that all employees experience. See 1 B. Lindemann & P. Grossman, Employment Discrimination Law 669 (3d ed. 1996) (noting that "courts have held that personality conflicts at work that generate antipathy" and "‘snubbing' by supervisors and co-workers" are not actionable under § 704(a)). The antiretaliation provision seeks to prevent employer interference with "unfettered access" to Title VII's remedial mechanisms. Robinson, 519 U.S., at 346, 117 S. Ct. 843, 136 L. Ed. 2d 808. It does so by prohibiting employer actions that are likely "to deter victims of discrimination from complaining to the EEOC," the courts, and their employers. Ibid. And normally petty slights, minor annoyances, and simple lack of good manners will not create such deterrence. See 2 EEOC 1998 Manual § 8, p 8-13.

Id. (emphases added).

Eisenstein appealed both retaliation findings in March, and was informed of PUC's response yesterday. PUC seemingly took FIRE's letter and the Court's ruling in Burlington Northern into account-but unfortunately, PUC has decided to wholly reject the Court's holding.

Despite the fact that it is a public institution and thus bound by the First Amendment and the Court's decision in Burlington Northern, PUC declared that Eisenstein's allegedly retaliatory remarks were not protected speech:

Because the statement does not pertain to a matter of public interest, it is not afforded the protections of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, and is therefore subject to Purdue University's Anti-Harassment policy. The University's Anti-Harassment policy and the Procedures for Resolving Complaints of Discrimination and Harassment are designed to further the University's interest in assuring an educational and employment environment that is free from discrimination and harassment. They are not the procedures of a court of law, nor are they to be interpreted narrowly. Such statement, made on account of the filing of a complaint and which causes or is likely to cause emotional or psychological harm, is not a "petty slight" or "minor annoyance" to which an individual filing a complaint (regardless ofthe merit of the underlying claim) should be subjected to under the University's policies and procedures. It is an overt act of reprisal.

Whatever the unpleasantness of Eisenstein's comments-one of which, again, Eisenstein denies having said-this is a wrongheaded decision on PUC's part.

First, PUC's proffered rationale that Eisenstein's speech "does not pertain to a matter of public interest" is a red herring. Whether or not Eisenstein's comments touched on a matter of public interest (in PUC's eyes, or someone else's) is irrelevant for the purposes of analyzing whether it rose to the level of "materially adverse" injury or harm necessary to sustain a retaliation finding, as laid out clearly by the Supreme Court in Burlington Northern. This is the touchstone inquiry for analyzing such a retaliation claim, and PUC's initial justification that Eisenstein's speech is automatically "not afforded the protections of the First Amendment" is thus incorrect.

Second, while PUC makes the often-seen argument that its policies and procedures "are not the procedures of a court of law," it is a public institution, bound by the First Amendment. As such, it does in fact have the obligation to interpret its policies addressing discrimination and harassment in accordance with the law governing employee speech. Terms like "retaliation" have specific legal definitions that must be followed in order to avoid punishing speech protected by the First Amendment.

Finally, PUC's contention that Eisenstein's speech "causes or is likely to cause emotional or psychological harm" confuses or ignores the applicable legal standard. Again, as the Supreme Court made clear in Burlington Northern, speech loses protection as retaliation only when it is "materially adverse," meaning that the allegedly retaliatory speech would have "dissuaded a reasonable worker from making or supporting a charge of discrimination."

The Court makes no mention of the vague terms ("emotional or psychological harm") that PUC is relying on to justify its finding of retaliation. Even more importantly, it specifically includes an objective component into its standard: To qualify as retaliation, the speech must be such that a reasonable employee would be dissuaded from filing charges of discrimination.

So even if an employee was able to demonstrate that he or she had suffered "emotional or psychological harm," the analysis isn't complete. The employee must also show that the harm was so significant that a reasonable worker would have been abandoned or withheld his or her discrimination charges. The inclusion of an objectivity standard is crucially important; otherwise, "retaliation" becomes whatever speech may dissuade the most unreasonably hypersensitive employee from following through on his or her discrimination charges. And again, the Court explicitly noted that "simple lack of good manners" isn't enough, and made clear that it was requiring "material adversity because we believe it is important to separate significant from trivial harms." (Emphasis added.)

So in Eisenstein's case, PUC has concluded that a single comment to one coworker and the decision to snub another are both sufficient examples of "material adversity" that would convince reasonable employees not to file or support discrimination charges. That seems like a gross underestimation of the mental fortitude of PUC professors-not to mention a misreading of the Court's guidance.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

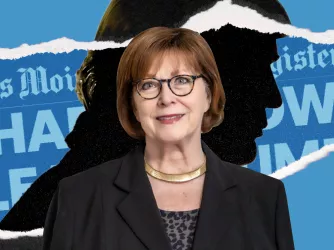

FIRE’s defense of pollster J. Ann Selzer against Donald Trump’s lawsuit is First Amendment 101

China’s censorship goes global — from secret police stations to video games

High schoolers: Become a voice for tomorrow, today!