Table of Contents

Ohio University implements new speech policies, reaffirms commitment to students’ First Amendment rights

After months of feedback from university governance bodies, students, faculty, staff, and community members, Ohio University announced last Friday the implementation of three new policies related to free expression on campus. In doing so, OU reaffirmed its commitment to the expressive rights of its students on campus, indoors and out.

OU’s new Statement of Commitment to Free Expression, explains that “[f]reedom of expression is the foundation of an Ohio [U]niversity education.” And it’s not just polite ideas that must be permitted:

Ohio [U]niversity welcomes free expression in all its forms, including the expression of dissent. Universities at their best are lively, sometimes tumultuous places. This is especially true here, where today we walk the same greens where our predecessors assembled to call for civil rights and an end to the Vietnam war, to mourn the assassinations of heroes, and to express concern for campus issues of their day. Recent years have shown this legacy of activism to be alive and well on our campuses. We welcome this, and we recognize that robust debate and civil disagreement are healthy signs of an engaged university community and a diversity of perspectives.

This broad commitment to the importance of the free expression of ideas — even, and perhaps especially, those that are controversial — is laudable. It fits perfectly with the Supreme Court’s continued guidance that “[t]eachers and students must always remain free to inquire, to study and to evaluate, to gain new maturity and understanding; otherwise, our civilization will stagnate and die.” Sweezy v. New Hampshire (1957).

OU also acknowledged that its goal is to expose its students to new ideas, not shelter them from those ideas that some may consider offensive or harmful: “Ohio [U]niversity does not shield its community from speech on the basis that it is uncomfortable, wrong, or offensive. Rather, Ohio [U]niversity seeks to prepare each student to engage thoughtfully and passionately with all ideas, even with disagreeable views.”

The two other revised policies fit well with these principles. OU's Use of Outdoor Spaces policy, allows for spontaneous protest and contains reasonable time, place, and manner regulations for open areas on OU’s campus. OU's Use of Indoor Spaces policy, even reopens much of Baker Center, the student center on campus, to protest, allowing expressive activity in:

Baker [C]enter: in the rectangular atrium spaces located on the south end of the third, fourth, and fifth floors, and in the lounge area overlooking the rotunda on the north end of the fifth floor.

Baker [C]enter: in publicly reservable conference rooms and meeting rooms in Baker center.

Classrooms that are otherwise empty[.]

Taken together, these policies acknowledge the importance of free speech, even speech that gives rise to conditions that are “sometimes tumultuous,” on OU’s campus. They also clearly define what speech is not allowed and where, in accord with First Amendment principles.

But the picture of free expression at OU has not always been so rosy.

Prior to 2015, OU was a “red light” school as a result of its policy prohibiting “mental harm to others,” defined as “any act which demeans, degrades, [or] disgraces any individual.” That policy was stricken from the books in February 2015 as the result of a FIRE Stand Up For Speech lawsuit in which I was the plaintiff. In a rewrite of its Student Code of Conduct that was completed shortly after the lawsuit, OU implemented policies that earned a “green light” rating from FIRE. OU is currently a “yellow light” school as a result of its Computer and Network Use policy, but this policy is being revised, so OU may eventually become a green light institution.

In 2017, it seemed like some of that progress had been lost. Seventy OU students and local community members were arrested for peacefully protesting in Baker Center during its normal operating hours. The “Baker 70,” as they became known, were charged with trespassing. The charges against those arrested were eventually dropped after one of the students was found not guilty at trial. The municipal court judge held that the fourth floor lobby in Baker Center’s rotunda was a “designated public forum” — a legal term of art for a government-owned piece of property that has intentionally been opened up for expression — and that OU’s actions in arresting them for trespassing were not narrowly tailored to further a compelling government interest. Those committed to the cause of student free speech rightfully celebrated this positive development.

But in response to the judge’s ruling, OU passed a now-replaced version of its Indoor Spaces policy, prohibiting all spontaneous protest inside all university buildings. Although this policy was constitutional on its face as a reasonable time, place, and manner regulation, I expressed concern in a blog post for JURIST that its seemingly-retaliatory implementation could violate the First Amendment. The law on the issue is not settled, but if shutting down all protest in response to speech you don’t like doesn’t violate the letter of the First Amendment, it certainly violates the spirit.

OU has mostly addressed those concerns with the implementation of its new Use of Indoor Spaces policy. Although the policy is not perfect — it still prohibits protest in the rotunda, where the 70 students were arrested for trespassing, thereby continuing to close what a judge ruled was a designated public forum — it goes a long way to restoring the expressive rights of students to protest in their student center and other spaces on campus. With this restoration, OU acknowledges not only its commitment to the First Amendment, but the historic role protest in that space has played.

These new policies are not so much a change of course for OU as they are a return to the great progress it has been making. Other universities should look to this progress as an example of how to revise policies and support the First Amendment. As always, FIRE remains ready to help schools with policy revisions so universities may best serve their noble purpose.

Isaac Smith is a former FIRE legal intern and a joint JD/MA candidate at the University of Cincinnati

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

Supreme Court must halt unprecedented TikTok ban to allow review, FIRE argues in new brief to high court

Australia blocks social media for teens while UK mulls blasphemy ban

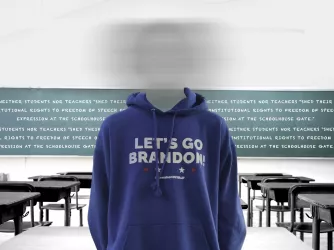

Free speech advocates converge to support FIRE’s ‘Let's Go Brandon’ federal court appeal