Table of Contents

New Clark College Statement on Free Expression Threatens Free Expression

I've been at FIRE long enough not to necessarily feel reassured when I read reports of a college or university promising to review and/or revise its free speech policies in response to student outcry over offensive speech. Sure enough, Clark College, a public two-year college in Washington State, has issued a new policy that threatens to undermine free speech, even as the college's president makes efforts to affirm it.

Clark College was rocked last fall when Clark student and alleged National Socialist Movement member Nathaniel Goncalves posted flyers around the campus promoting "white pride." The Clark community responded with various measures of counter-speech, including these flyers, and held forums with the community to discuss the incident's impact. Months later, on May 19, Clark capped off its institutional response to the incident by releasing a new statement on "Diversity and Free Expression at Clark College." At first the statement doesn't look so bad, and Clark President Bob Knight seems to say the right things regarding protecting offensive speech in The Independent, telling the campus newspaper that "I don't like it. I detest it. But I can't stop it."

Constitutionally speaking, Knight is right. As we commonly point out here, the vast majority of what we call "hate" speech is still free speech. The First Amendment and the principles behind it require that we answer speech that offends us with our own speech, not censorship. Goncalves' flyers can be cause for condemnation, but they can't serve as the basis for punishment or silencing.

Unfortunately, while Knight demonstrates an understanding of the impermissibility of censorship, Clark's newly released statement makes several of the same mistakes we see in campus speech codes that unconstitutionally restrict student rights around the country.

The one-page statement opens with a declaration of the "Values of the Clark College Community," which it imports from the Carolinian Creed in effect at the University of South Carolina. In part Clark's new statement says:

As members—students, staff, faculty and administrators—of the academic community, we enjoy the privileges and share the obligations of the larger community of which the College is a part. With membership in this community comes an obligation, which is consistent with the goals of personal and academic excellence. This obligation is an acceptance of a code of civilized behavior. These are the guiding principles for all at Clark College:

"I will practice personal and academic integrity. I will respect the dignity of all persons. I will respect the rights and property of others. I will discourage bigotry. I will learn to respect differences among people, ideas, and opinions. I will demonstrate concern for others, their feelings and their need for conditions, which support their learning, work and development. Allegiance to these ideals obligates each individual to refrain from and discourage behaviors which threaten the safety and well-being of all community members."--based upon the Carolinian Creed [Emphases added.]

FIRE has written plenty of times before on the problematic nature of such statements when they are made mandatory to students. In our brochure Correcting Common Mistakes in Campus Speech Policies, we cited the Carolinian Creed (which is rated a "red light" in our Spotlight database) as emblematic of the problems with such campus creeds and oaths:

While these values—and the values contained in similar policies at universities nationwide—may seem uncontroversial and even admirable, a university cannot require its students to categorically agree to them without violating basic rights to private conscience and academic freedom. Specifically, universities cannot require students to swear allegiance to an official set of university values. As the U.S. Supreme Court famously stated in a 1943 decision upholding the right of Jehovah's Witnesses not to salute the U.S. flag, "If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein."

Further, statements like these seem to require students to regulate their expressive activity on campus in accordance with impermissibly vague terms-the Carolinian Creed referenced above, for example, refers to "dignity" and "concern for others"-that could, in application, mean virtually anything. These vague terms force students to guess at what expressive activity is and is not allowed on campus-and such guessing results in self-censorship and a chilling effect on student speech. Statements like these are often not only unconstitutionally vague but overbroad as well. In other words, they often prohibit students from engaging in protected speech. (The vast majority of speech that does not "demonstrate concern for others," for example, is protected by the First Amendment.)

As we've also written many times before, a very simple fix exists to address these problems: making clear that such creeds are merely aspirational and that students will not receive sanctions for not following them. Penn State's modification of the "Penn State Principles" stands out as an example of universities correcting their policies in this manner to ensure student free speech is protected. Were it not for the borrowing of USC's policy language, in fact, Clark's later statement on "Free Expression -- Our Values" would do just fine in signifying that it prizes certain virtues without forcing them on students:

However, any expression of hatred or prejudice is inconsistent with the values of Clark College and the purposes of higher education in a free society. So long as intolerance exists in any form in the larger society, it will be an issue on college campuses. Clark College is committed to maintaining an environment free from prejudice, inequity, and the misuse of power and privilege, and will use opportunities such as open dialogues, debates and discussions to broaden understanding of the scope of protected speech and the role of tolerance in our community.

Unfortunately, it then proceeds to give a significantly overbroad definition of harassment:

Conduct which unreasonably disrupts, adversely affects, or otherwise interferes with the lawful functions of the College, or the rights of any individual to pursue an education and/or employment at the College will not be tolerated.

This falls far short of the Supreme Court's requirement that for conduct or speech to become actionable harassment in the university setting, it must be "so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive, and [] so undermines and detracts from the victims' educational experience, that the victim-students are effectively denied equal access to an institution's resources and opportunities." Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, 526 U.S. 629, 651 (1999).

As a result of these structural infirmities, much speech at Clark that is protected by the First Amendment will be chilled, and students are at risk of being wrongly sanctioned by the college for their expression. President Knight isn't alone among college presidents when he says of offensive speech that "I can't stop it." He's also, unfortunately, not alone in enacting speech codes that belie such statements. Hopefully the dialogue that has resulted from this incident will continue with a discussion of universities' obligation to uphold the First Amendment, as well as this statement's shortcomings.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

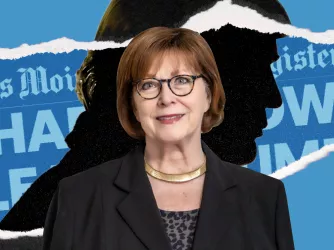

FIRE’s defense of pollster J. Ann Selzer against Donald Trump’s lawsuit is First Amendment 101

Cosmetologists can’t shoot a gun? FIRE ‘blasts’ tech college for punishing student over target practice video

China’s censorship goes global — from secret police stations to video games