Table of Contents

Irvington Township, NJ’s response to public records requests: Go to jail, do not pass go, do not collect $200

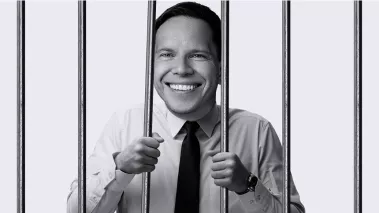

Artistic depiction of FIRE attorney Adam Steinbaugh, shown here in prison for submitting open records requests.

As an attorney at FIRE, I send a lot of public records requests. Last year, I tallied about 750. Two of them went to Irvington Township, New Jersey — and now Harold Wiener, its municipal clerk, is calling for my prosecution.

Why?

Because I asked for records about the last time Irvington Township tried to use the legal system to deter people from asking for public records — and then complained when Irvington blew me off.

Irvington Township may sound familiar because of the embarrassing national and international headlines it earned last year when it sued an elderly resident, Elouise McDaniel, for sending 75 such requests in three years — as NJ.com noted, that “comes out to one every two weeks.” McDaniel, a retired teacher and local political activist, requested things like job descriptions of township officials, the costs officials incurred to attend conferences, and copies of township resolutions.

Wiener and Irvington Township’s lawsuit against McDaniel claimed she had sent “frivolous” letters complaining about Irvington to the U.S. Senate, and that she “bullied and annoyed” city officials. It also claimed she had defamed the mayor and unidentified municipal employees. How? Irvington refused to say, telling the court it could only provide allegations “under seal to safeguard the identity” and “reputation” of — well, it’s a secret.

Before the lawsuit landed Irvington in the media spotlight, the township — and mayor Anthony Vauss — retained another law firm to discourage critical media attention. That firm sent a “CONFIDENTIAL” letter to a journalist at NBC New York, Christopher Glorioso. This second firm accused Glorioso of “biased and harassing journalism” and demanded that he cease “assist[ing] Elouise McDaniel, a well-known political operative and adversary” of Mayor Vauss.

Wiener’s response to the second complaint went nuclear, demanding that I be prosecuted.

That effort to intimidate Glorioso failed: NBC New York published the story and showed part of the township’s cease-and-desist letter. And when confronted by the media, nobody associated with the township wanted to claim responsibility. Mayor Vauss reportedly told the NBC reporters “he had not seen or read the lawsuit and didn’t know the details of why Irvington filed it,” pointing the finger at Wiener — who, in turn, said he “hadn’t requested a lawsuit against” McDaniel.

After Irvington was pilloried for its bogus lawsuit, it sheepishly dropped it, citing a desire to avoid legal fees.

All of that seemed fishy. If Wiener and Vauss weren’t aware of the lawsuit, how did it get filed? And because governments can’t be defamed, why were a law firm claiming to represent Irvington and Vauss and the Township of Irvington sending letters about the mayor’s political “adversary”? That seems like a personal concern, not a township concern.

How much did this cost taxpayers? Who authorized it?

I sent Wiener a public records request of my own, asking for the township’s retainer agreements and invoices, as well as the cease-and-desist letter sent to NBC New York. Mayor Vauss, after all, pledged, “We don’t want people to think we don’t want them to request information. We’re not trying to stop anyone from getting information.”

Irvington blew that request off, so I filed a complaint with New Jersey’s Government Records Council — an alternative to filing a lawsuit against the city. That complaint was sent under penalty of perjury. So was Wiener’s response, which required him to describe the specific steps Irvington took to locate the requested records. But Wiener’s list — again, of every effort Irvington made to search for records — only listed an email a staff member sent me. This suggests that Irvington didn’t even bother to look for responsive records.

So I sent a second public records request, this one asking for records of their search for records. Once again, Irvington blew it off — and, once again, I filed a complaint.

Wiener’s response to the second complaint went nuclear, demanding that I be prosecuted:

[New Jersey’s] Open Public Records Act requires that “government records be readily accessible for inspection . . . by citizens of this State . . .” (emphasis added). The Complainant (“Requestor”) has certified by penalty of perjury that he or she is a resident of the State of Pennsylvania. Therefore, the Open Public Records Act does not apply to Requestor and access could not have been denied to Requestor.

[ . . . ]

Accordingly, the instant Complaint and all future Complaints filed by the Requestor must be dismissed on their face and/or Requestor’s perjury must be reported to law enforcement for prosecution under [New Jersey’s perjury statute]. The Township should also be absolved from responding to any of Requestor’s OPRA requests.

Wiener’s grand theory, as I understand it, is that I — by submitting a public records request, or a complaint to the GRC — am implicitly asserting that I am a citizen of New Jersey, which I am not. And, according to Wiener, only New Jersey citizens can file public records requests.

But that is not the law.

Demanding that a public records requestor be criminally prosecuted is unusually bold.

A handful of states, like Virginia and Tennessee, do limit their public records laws to citizens of the state, a practice upheld by the Supreme Court in McBurney v. Young. But New Jersey is not one of those states: Its courts rejected the argument that the “citizens of this state” language cited by Irvington means that only New Jersey citizens can request public records. The GRC then ruled that the New Jersey courts “laid to rest” the question. And New Jersey’s attorney general agrees.

One might query whether Irvington’s leaders know or care what the law is. As one of the longest-serving municipal clerks in New Jersey, Wiener’s knowledge of the law is said to be “unsurpassed.” Irvington Township — when it’s not blowing off public records requests or being held in contempt for failing to comply with the law — views the legal system as a cudgel to punish or intimidate people who send them a public records request. Demanding that a public records requestor be criminally prosecuted is unusually bold.

But it won’t intimidate me. If Harold Wiener thinks it’s a crime to send him a public records request, he can call 911.

And then I’ll send a public records request for the 911 call audio.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

FIRE statement on immigration judge’s ruling that deportation of Mahmoud Khalil can proceed

FIRE welcomes Allison Hayward to board of directors

‘Executive Watch’: The breadth and depth of the Trump administration’s threat to the First Amendment — First Amendment News 465