Table of Contents

Free speech isn’t a contender at the 2022 World Cup

Danielle Parhizkaran / USA TODAY Sports

Players from Iran and the United States of America during the national anthems before a group stage match during the 2022 World Cup at Al Thumama Stadium in Doha, Qatar.

Depending on who you ask, you’ll get a different answer about what’s center stage at the World Cup right now. Is it football? Maybe soccer?

Or is it whitewashing?

For critics of FIFA’s decision to hold the event in Qatar, the games themselves take a backseat to the ethics of hosting a major sporting event amid the backdrop of human rights abuses, like the country’s treatment of migrant workers and its criminalization of homosexuality.

FIFA President Gianni Infantino attempted to combat this criticism in a press conference ahead of the games, claiming the “one-sided moral lesson is just hypocrisy.”

“I don’t have to defend Qatar, they can defend themselves. I defend football. Qatar has made progress and I feel many other things as well,” Infantino explained. Citing his childhood “red hair and freckles,” he added, “Of course I am not Qatari, Arab, African, gay, disabled or a migrant worker. But I feel like them because I know what it means to be discriminated and bullied as a foreigner in a foreign country.”

He also wrote, in a letter to all competing teams, “[P]lease do not allow football to be dragged into every ideological or political battle that exists.” His strategy echoes that of the International Olympic Committee, which deflected questions and complaints about the human rights abuses in China around the 2022 Beijing Olympics.

Teams, players, journalists, and fans encounter censorship

But ideological and political battles nevertheless plague the games, whether Infantino likes it or not. Since before the World Cup even began, a series of public disputes over how fans, players, and teams could express themselves caused headaches for FIFA.

Captains from seven European teams, including England and Germany, originally planned to display OneLove rainbow armbands until FIFA threatened yellow cards for players wearing them. Regarding Qatar’s criminalization of homosexuality, Infantino said at his press conference, “How many gay people were prosecuted in Europe? . . . Sorry, it was a process. We seem to forget.”

The teams said they were “very frustrated” by the “unprecedented” decision and “were prepared to pay fines that would normally apply to breaches of kit regulations” but were unwilling to accept in-game penalties that would hinder gameplay. Germany’s team tweeted a picture of its players covering their mouths in protest of the decision, and stating that the armband “wasn’t about making a political statement.” They added, “Denying us the armband is the same as denying us a voice.” FIFA also demanded Belgium’s team change its away jerseys to eliminate the word “love” from the inside collar.

It wasn’t just players whose speech was limited by FIFA. Multiple journalists reported negative interactions with Qatari security, including Danish journalist Rasmus Tantholdt, whose camera was blocked and shoved by security. American sports analyst Grant Wahl had two run-ins with officials. First, security guards forced him to delete a picture he took on his phone at the media center. After that, he was disallowed by security from entering the stadium, and temporarily detained, because his shirt, which showed a rainbow around a soccer ball, was “not allowed.”

The protests sparked in Iran by Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman who died after her arrest by the country’s morality police, also found their way into the World Cup. Iranian fans holding pre-revolutionary flags as a statement against the country’s government were denied entry to the team’s game unless they handed the flags over to security. The same went for fans wearing protest shirts, which had to be turned inside out.

More concerningly, Iran’s team could face repercussions for its own small act of protest during the games. In their game against England, the players chose to remain silent, rather than sing along, during their country’s anthem. As the protesters in China have demonstrated so well, what we don’t voice can be just as powerful as what we do.

The laws of Qatar are, to put it mildly, a pretty big asterisk in university policy.

Some Iranian figures seemingly agree that the protest is notable — and they’re not pleased. Mehdi Chamran, chairman of Tehran’s city council, said Iran “will never allow anyone to insult our anthem and flag” and another politician called for the team to be replaced with supporters of the government. A newspaper loyal to the country’s supreme leader accused “foreign media” of a “ruthless and unprecedented psychological-media war . . . to create a gap between the people of Iran and the members of the Iranian national football team.” It’s not clear if or how the Iranian government will ultimately respond, but its treatment of protesters at home continues to worsen.

It may suit leaders like Infantino, the International Olympic Committee, or Qatari officials to act as if their games should be immune from politics and controversy. But by acting to remove some kinds of expression from the arena, they’re making political statements of their own — whether they admit it or not.

Censorship in Qatar is old news for American universities

The suppression of certain viewpoints at the World Cup is a disappointment, to be sure. But it’s no surprise. After all, this is a lesson universities that have expanded into Qatar, and the Gulf states broadly, have learned all too well. As I told Patrick Jack at Times Higher Education last week, FIFA “is getting a crash course in what American universities have been slowly experiencing over the past decade.”

FIRE has covered this censorship, and the perils of opening satellite campuses in unfree countries like Qatar and China, for years. In 2018, Georgetown University in Qatar canceled a debate about whether “major religions should portray God as a woman” after the hashtag, “Georgetown Insults God,” went viral online. Georgetown initially claimed the event didn’t follow event approval guidelines, but its office of communications then admitted the debate “created a risk to safety and security of our community” and that the university “is committed to the free and open exchange of ideas, while encouraging civil dialogue that respects the laws of Qatar.” The laws of Qatar are, to put it mildly, a pretty big asterisk in university policy.

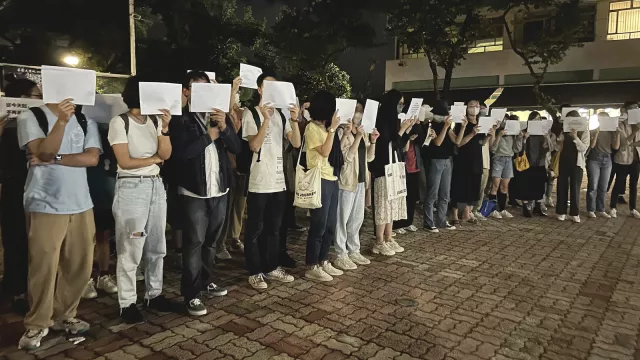

Protests are sweeping heavily censored China. How will American institutions respond?

Thousands of people in cities and universities across China have joined mass demonstrations sparked by a deadly fire in Urumqi, which many fear was worsened by the country’s pandemic lockdown policies.

FIRE challenged Georgetown over the cancellation, citing the university’s free speech commitments, but the university doubled down, saying (emphasis added) that students “may host events on campus that are in accordance with Qatari law.”

A little over a year after the Georgetown debate cancellation, Northwestern University’s Qatar campus experienced its own controversy after it canceled an event featuring a gay musician, citing security issues. FIRE criticized Northwestern’s behavior here too, suggesting that satellite campuses were promising students rights that they couldn’t deliver in practice.

And then the Qatar Foundation, a state-linked nonprofit and a partner of Northwestern, told media that Northwestern was essentially lying about the reasons for the cancellation. It wasn’t canceled due to “security concerns,” as Northwestern claimed. Instead, it was canceled because it “patently did not correlate” with “Qatari laws as well as the country’s cultural and social customs.” Northwestern, at the time, denied the foundation’s account, saying it “respectfully disagree(s)” with the comments and reaffirming its claims about security concerns.

The university’s official statements, hard to believe two years ago, are even less believable now. Patrick Jack’s recent piece in Times Higher Education includes an interview with Craig LaMay, who was dean at Northwestern’s Qatar campus during the controversy. LaMay outright says the Qatar Foundation told the campus to cancel the event.

“Professor LaMay said that while he was dean of the Northwestern campus, he was ordered by the Qatar Foundation – the state-led organisation that runs Education City – to shut down an event because a band with an openly gay lead singer was on the schedule,” Jack wrote.

In short, both the dean of the campus at the time and Northwestern’s on-the-ground partner in Qatar are very clear: The Qatar Foundation directed Northwestern, an American university with strong commitments to speech and academic freedom, to cancel an event because it conflicted with Qatari values. Still, Northwestern repeatedly denies this.

Northwestern’s students and faculty in both Evanston, Illinois, and Education City in Qatar should be asking some very tough questions of university leadership right now: Did Northwestern lie about the series of events triggering the 2020 event cancellation? And does the Qatar Foundation make the calls over what can be said on Northwestern’s campus? The university community deserves the truth.

The World Cup may serve as a useful branding opportunity for Qatar, whose leaders want to shift the narrative away from state suppression of human rights and abuse of migrant workers and onto platitudes about engagement and cooperation. But no matter how successful this PR campaign is, it can’t paper over the reality of censorship and human rights abuses on the ground. American satellite campuses have illustrated this well enough.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

FIRE's 2025 impact in court, on campus, and in our culture

The trouble with banning Fizz

VICTORY: Court vindicates professor investigated for parodying university’s ‘land acknowledgment’ on syllabus