Table of Contents

Florida school district removes library books in response to public complaints, defying First Amendment and district policy

On The Run Photo / Shutterstock.com

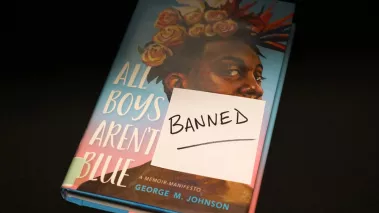

"All Boys Aren't Blue," a memoir by journalist and LGBTQ activist George M. Johnson, is one of several books that are no longer available in Osceola County schools after complaints by community members.

At an Osceola County School Board meeting last April, several community members objected to the content of certain books in the school district’s libraries. Two days later, the district violated its own policies and removed the books pending committee review. Eight months after that, the books remain in limbo, despite the committee’s recommendation to reshelve them.

FIRE wrote the school board in late December, explaining that its actions flout the First Amendment and the district’s own policies. We called on the board to accept its committee’s recommendation to restore the books and to preserve its libraries as a space where students can freely explore different ideas and perspectives.

Concerns raised at school board meeting

During public comments at the Osceola County School Board meeting on April 5, several parents and community members complained about certain books carried in the district’s libraries, including “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” “Me, Earl, and the Dying Girl,” “Looking for Alaska,” “Gender Queer,” and “Out of Darkness.” One commenter raised concerns about “grooming” kids and “transgenderism,” while another quoted a Bible passage stating God created male and female, and told the board to “stop grooming children to think they can change their gender.” Other commenters read passages about sex from the books.

On April 7, Osceola County Superintendent Debra Pace ordered all district libraries to remove the books and said a committee would review them to recommend whether the district should retain them. That process violates district policy, which states that parents and residents can challenge library books only by submitting a written objection using a district-provided form. At a subsequent school board meeting, Chairwoman Terry Castillo admitted that the district “didn’t follow the rules at all,” as “no one filed a complaint against any of these books” and “Dr. Pace pulled them based on public comment.” Castillo added that “there’s not one single parent that’s appealing” the committee’s recommendation.

Before their removal, none of the books were available in libraries serving K-5 grade levels, and only two (“Looking for Alaska” and “Me, Earl, and the Dying Girl”) were available for sixth and seventh graders.

The committee’s recommendations largely tracked the books’ initial availability. Over the summer, the committee recommended keeping “Out of Darkness,” “Me, Earl, and the Dying Girl,” and “All Boys Aren’t Blue” in high school libraries only, and making “Looking for Alaska” available in high school and middle school libraries. (The district also removed a fifth book, “Tricks,” from its libraries in August, but no recommendation has been made regarding that book.)

Months later, the books remain unavailable in all Osceola County school libraries.

District policy requires multiple rounds of thorough committee review and appeals before the matter reaches the board.

After FIRE sent its letter, Superintendent Pace immediately responded, confirming that the district will review the letter and respond after the holidays. Pace added that Osceola County is awaiting guidelines from the Florida Department of Education regarding media center access and staff training “before bringing forward a recommendation to the Board regarding the 5 books currently under review.” She also said the board “requested additional time to read and review the books for themselves before taking action on the recommendations of the review committee.”

The superintendent’s response ignores that, under the district’s own policies, no review should have occurred in the first place. Further, the district’s ad hoc determinations, and continued inaction in the face of its own committee’s recommendation to reshelve the books, fall short of what the First Amendment demands.

Osceola County flouts its own policies

Osceola County School Board rules governing library book challenges first require the school’s media specialist to meet with the objecting parent or resident to discuss the school’s procedure for selecting materials. If that mediation fails, the complainant must submit a “formal written objection” using a district-provided form, “which must reflect that the complainant has read the material in full.”

No such objection was filed, tainting the whole process from the start.

Even if anyone had filed a formal challenge, district policy requires multiple rounds of thorough committee review and appeals before the matter reaches the board. Instead, the board and superintendent disregarded this process and took matters into their own hands, ordering all Osceola school libraries to remove the books after several community members verbally objected to their content and read brief, cherry-picked passages from the books at a school board meeting. The district then formed a review committee — only to ignore, for months, that committee’s recommendation to reshelve the books.

Students’ First Amendment rights ‘directly and sharply implicated’ by removal of books from a school library

The district’s actions are remarkably similar to those of the Long Island school board at issue in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 v. Pico. In that 1982 Supreme Court case, a public school board removed several of its library books that were on a list obtained from an organization of parents concerned about education. The board formed a committee to review the books, then rejected the committee’s recommendation to retain five of the books without restriction.

Show-Me state censorship: Proposed new rule threatens Missouri’s public libraries

News

A proposed rule in Missouri would restrict public libraries from using state funds to purchase books that discuss sex and would allow "any person" to challenge those materials.

The plurality decision in Pico, authored by Justice William Brennan, explained that students’ First Amendment rights are “directly and sharply implicated by the removal of books from the shelves of a school library,” as the First Amendment protects not only individual self-expression but the “right to receive information and ideas.” While local authorities have discretion to determine the content of their school libraries, “that discretion may not be exercised in a narrowly partisan or political manner.” Justice Harry Blackmun’s concurring opinion likewise explained that school authorities “may not remove books for the purpose of restricting access to the political ideas or social perspectives discussed in them, when that action is motivated simply by the officials’ disapproval of the ideas involved.” The Court noted evidence that the board removed the books at least in part based on objections to their ideas, and emphasized the lack of reliance on “established, regular, and facially unbiased procedures for the review of controversial materials.”

Osceola County’s removal of books from its school libraries suffers from the same deficiencies. As FIRE told the school board:

Not only did the board here violate district policy, it failed to exercise its discretion over educational matters “in a manner that comports with the transcendent imperatives of the First Amendment.” Nothing about the board’s process—or lack thereof—evinces an impartial, good-faith effort to holistically assess the books’ educational suitability. Instead, Osceola County hastily capitulated to criticism and pressure from several community members to remove the books—criticism that focused not only on sexually explicit language in the books but also on their ideas, in particular themes of gender identity. Pico’s emphasis on adherence to fair, established procedures is intended to prevent exactly this type of result.

Osceola County’s culling of its school library collections follows a nationwide trend. Head north on I-95 for a few hours and you’ll hit Duval County, Florida, where 176 books were removed from school libraries one year ago for “review.” The purge included a biography of Rosa Parks, a “Berenstain Bears” book, and hundreds of other titles that are still in storage as of December. A Nebraska public school board reportedly removed “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” “The Color Purple,” and other books from its libraries. In South Carolina, Beaufort County School District removed 97 challenged books for review, including “The Kite Runner,” “The Bluest Eye,” and “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

In the debate over school library book bans, it’s important to keep a couple of points in mind.

Library materials ≠ curriculum

Public K-12 school districts rightly have broad discretion in setting the curriculum. As FIRE President and CEO Greg Lukianoff and others explained last year amid the intensifying debate over the teaching of “critical race theory” in schools:

Because K-12 attendance is compelled by the state and, at public schools, funded predominantly by local taxes, it is understandable that the substance of that teaching is subject to democratic oversight, through state legislatures and elected (or appointed by those who were elected) school boards. Legislators are expected to exercise oversight when citizens with children in the schools voice legitimate concerns about curricular matters.

The Pico Court likewise acknowledged local school boards’ wide latitude to establish curriculum for the purpose of transmitting “community values” and “promoting respect for authority and traditional values be they social, moral, or political.” But, as the Court recognized, school library books are different from curricular materials in one very important aspect: No student is required to read them.

Unlike textbooks and assigned readings in class, Justice William Brennan reasoned, the “selection of books from these libraries is entirely a matter of free choice; the libraries afford [students] an opportunity at self-education and individual enrichment that is wholly optional.” School boards may consider relevant factors like “educational suitability” when selecting library books, but they may not remove books from a library simply because they or certain community members “dislike the ideas contained in those books.”

Parental control is possible without imposing blanket bans

Even though school library books are an optional resource for students, a parent may still want to prevent their child from checking out books the parent deems inappropriate for the child’s age or maturity level. It’s worth noting that none of the challenged books in Osceola County were available to K-5 students, and the county’s criteria for selecting library materials already take into account “maturity levels of the students being served.” Considerations of age-appropriateness are a standard part of librarians’ professional responsibility.

Libraries must be a space where students can freely explore the wide world of ideas beyond the classroom.

Granted, some parents may disagree with a librarian’s assessment of these factors. But, as FIRE told Osceola County, pulling books off the shelves does not advance the interest of parental oversight; it instead allows “a vocal minority of parents and other residents to speak for all parents in the community, some of whom may want their children to have access to the challenged books.” We further explained:

After all, different parents inevitably reach different judgments about what content their kids are mature enough to handle or understand. But there is an easy solution, which Osceola County appears to be implementing: The district can create a way for parents to request that a school restrict their own child’s access to certain library materials. That would be a preferable—and constitutional—alternative to flatly denying all students access to material that a few parents or community members consider objectionable.

This simple, common-sense solution should satisfy everyone and prevent America’s public school libraries from degenerating further into yet another partisan battleground. Libraries must be a space where students can freely explore the wide world of ideas beyond the classroom, preparing them for what the Supreme Court described as “active and effective participation in the pluralistic, often contentious society in which they will soon be adult members.”

FIRE looks forward to reading Osceola County’s promised response to our letter later this month.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

One day after FIRE lawsuit, Congress passes changes to filming permits in national parks

VICTORY: FIRE lawsuit leads California to halt law penalizing reporters, advocates, and victims who discuss publicly known information about sealed arrest records

O holy fight: New Hampshire Satanic Temple statue threatened by more than vandals