Table of Contents

FIRE supports the right to parody and a more limited application of qualified immunity in new amicus brief

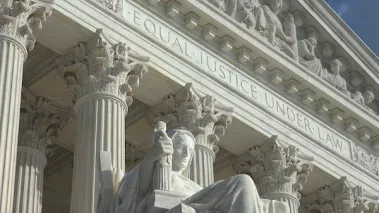

Bob Korn / Shutterstock.com

FIRE explained in its brief that the First Amendment clearly protects parody, but government entities, including colleges and universities, still punish it by exaggerating its disruptive effects.

Yesterday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit granted FIRE’s motion to file an amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief in support of Anthony Novak, who created a parody Facebook page poking fun at the City of Parma, Ohio’s police.

Despite Novak’s activity being clearly protected by the First Amendment, the police investigated his Facebook page and arrested him for electronically “disrupting” or “interfering” with police operations, as some members of the public had contacted police to complain about the page. A jury acquitted him of those charges, and Novak filed a civil suit against the city and the officers involved in the arrest and prosecution. However, the district court extended qualified immunity to the police officers who violated Novak’s rights and granted summary judgment to the defendants on all claims. Novak appealed.

FIRE has often seen institutions embellish the level of disturbance caused by expression they don’t like.

FIRE explained in its brief that the First Amendment clearly protects parody, but government entities, including colleges and universities, still punish it by exaggerating its disruptive effects. In doing so, government entities allow a “heckler’s veto” — that is, giving in to negative public reactions to speech by silencing or punishing the speaker. When courts are too broad in their application of qualified immunity — which is invariably asserted as a shield from liability by government actors sued for constitutional violations, including campus administrators — it impedes victims whose rights are infringed from obtaining damages to compensate for that past harm.

Courts should be skeptical of arguments that claim parody, satire, or other critical speech causes disruption warranting censorship, or that public reaction to the speech justifies censorship. As we stated in the brief:

When officials claim disruption, disturbance, or harm caused by speech that is directed against the government, courts should be especially circumspect for two reasons. First, because public safety is typically deemed a compelling government interest often granted deference by the public and our legal system, government actors may exaggerate the effects of claimed disruption to justify actions against unpopular speakers. Second, the risks are exacerbated when there is no functionally transparent tool by which to challenge claimed interests in preserving public order.

FIRE has often seen institutions embellish the level of disturbance caused by expression they don’t like. Our brief cites just a few examples, including situations at Essex County College, Babson College, and Rutgers University.

FIRE also has been sounding the alarm on the doctrine of qualified immunity for decades, and its application was particularly concerning here. As we explained to the Sixth Circuit:

Often, qualified immunity is granted when police confront split-second decisions, sometimes involving life and death, that violate a plaintiff’s constitutional rights. The rationale for qualified immunity carries more weight in such cases, where officers make heat-of-the-moment decisions. But that is not true of this case and others like it [where] the City’s conduct in investigating and arresting Novak was deliberate, considered, devised and pursued over a matter of weeks, giving officers ample time to determine whether they would be violating Novak’s constitutional rights.

When deciding whether to grant qualified immunity, courts must decide whether the constitutional right at issue was “clearly established” at the time the right was violated. We argued the law presents two potentially conflicting standards for what it means to be “clearly established,” and that the Sixth Circuit should commit to using the less restrictive one in cases like this (and their analogues on campus):

This Court should commit to the standard … that the law is “clearly established” when it provides “fair notice” that conduct is unconstitutional, particularly (but not necessarily limited to) when government actors have time to deliberate and consider their actions. If qualified immunity is instead interpreted to require near mathematical precision as to factual circumstances—a risk under the “beyond debate” standard as used [by the trial court in Novak] below—those who have had constitutional rights infringed are doubly harmed, because they are later impeded in vindicating those rights.

In support of this approach, we cited Justice Thomas’ statement in the Supreme Court’s recent denial of certiorari in Hoggard v. Rhodes, a case arising out of Arkansas State University-Jonesboro, another in which FIRE submitted an amicus brief. Justice Thomas wrote that the Court’s qualified immunity doctrine “stands on shaky ground” and that its “one-size-fits-all doctrine” is “an odd fit for many cases because the same test applies to officers who exercise a wide range of responsibilities and functions.”

As another federal appellate court subsequently noted, also quoting Justice Thomas’ Hoggard statement:

Why should university officers, who have time to make calculated choices about enacting or enforcing unconstitutional policies, receive the same protection as a police officer who makes a split-second decision…?

You can read FIRE’s full brief here.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

FIRE's 2025 impact in court, on campus, and in our culture

The trouble with banning Fizz

VICTORY: Court vindicates professor investigated for parodying university’s ‘land acknowledgment’ on syllabus