Table of Contents

FIRE submits concerns over Harvard harassment policy proposals

FIRE sent a letter to Harvard University today detailing serious free speech and due process concerns about a series of policy proposals open for public comment through tomorrow.

If implemented, these policies and procedures — Harvard’s Draft Non-Discrimination and Anti-Bullying Policies and Procedures, Interim Title IX Sexual Harassment Policies and Procedures, and Interim Other Sexual Misconduct Policies and Procedures — would threaten students’ free speech and due process rights.

To better safeguard students’ rights, FIRE’s letter explains that Harvard must:

- Revise the overbroad definitions and examples of harassing conduct in the proposed policies,

- Reverse course on a problematic definition of consent, and

- Revise the proposed procedures to provide students sufficient due process protections in disciplinary proceedings.

We commend Harvard’s transparency in making these policy drafts public, and seeking input from campus constituents. Accordingly, we now address the main policy concerns and suggested revisions.

Overbroad definitions and examples

Speech that is included in harassment isn’t protected under First Amendment standards (which, by the way, are standards Harvard commits to uphold, despite being a private institution).

However, harassment must meet a specific legal definition to be punishable. As the Supreme Court made clear in Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, peer harassment in the educational setting is conduct that is “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive, and that so undermines and detracts from the victims’ educational experience, that the victim-students are effectively denied equal access to an institution’s resources and opportunities.” Harvard’s proposals fail to sufficiently track this standard.

All of Harvard’s definitions of bullying and harassing conduct from these policies must be revised to track the Supreme Court’s speech-protective standard.

For example, the proposed other sexual misconduct policy only requires that conduct is “severe” or “pervasive, rather than “severe” and “pervasive” and “objectively offensive.”As a result, this policy could too easily be applied to restrict protected speech that is severe, but not pervasive or objectively offensive. Under such a vague standard for harassment, a single, severe statement made at a campus protest about an inflammatory topic could trigger disciplinary action. (FIRE has seen this play out too many times, like when American University investigated students for harassment when they discussed abortion in a group chat.)

All of Harvard’s definitions of bullying and harassing conduct from these policies must be revised to track the Supreme Court’s speech-protective standard, so students aren’t discouraged from engaging in controversial or unpopular speech that could be targeted under weaker definitions.

Additionally, the draft anti-bullying policy’s list of examples, such as “derogatory remarks, epithets, or ad hominem attacks,” invites restriction of protected speech.

While it’s reasonable for the university to list examples of conduct that may be included in punishable, bullying behavior for illustrative purposes, this proposal features a common pitfall: The list of examples doesn’t clearly explain when those examples actually cross the line and become punishable conduct, and instead implies that the examples are banned across the board.

This policy should be revised to make clear that any listed examples of bullying behavior still have to be a part of a pattern of conduct that constitutes hostile environment harassment to be punishable.

Problematic definition of consent

Both Harvard’s Title IX sexual harassment policy and other sexual misconduct policy adopt a new definition of consent to engage in sexual activity, recommended by Harvard’s Title IX and Other Sexual Misconduct Policy Working Group:

This Policy requires consent to engage in sexual activity with another person. Specifically, it is the responsibility of anyone participating in sexual activity to obtain the consent of the other participant(s). It is important not to make assumptions about consent if confusion arises during a sexual interaction.

Consent is active, mutual agreement given voluntarily and may be communicated verbally or by actions.

The definition additionally states that consent is not voluntary if it is obtained by coercion, consent can be withdrawn at any time, a person may consent to some kinds of sexual activity and not others, and a person may consent to participate in sexual activity on one occasion and may choose not to do so on a later occasion. It further states that engaging in sexual activity with someone a respondent knew or reasonably should have known was incapacitated constitutes sexual misconduct.

Having an advocate who is permitted to make arguments during proceedings is essential, because not every student is capable of being a strong oral advocate on their own behalf when undergoing this potentially life-altering, and often confusing, process.

While all are surely good personal practices, this affirmative consent standard fails to provide students sufficient notice of what behavior is prohibited. For example, it’s unclear whether the standard requires, for example, asking for permission before touching each body part; a concern that has been raised for years regarding similar affirmative consent standards.

This standard also impermissibly places the burden of proof on the person accused of misconduct, effectively forcing the respondent to prove they obtained active, mutual consent throughout the encounter. Deeming students accused of misconduct “guilty until proven innocent” is an impermissible threat to due process rights.

Instead, Harvard should employ a standard of consent by which any communication of withdrawal of consent renders subsequent activity assault (absent coercion or incapacitation), and make clear that the university bears the burden of demonstrating that consent was lacking. (You can read more about FIRE’s position on affirmative consent here.)

Insufficient due process protections

Each of the proposed procedures fail to provide accused students sufficient due process protections as they undergo disciplinary proceedings.

For example, neither the proposed non-discrimination policy and anti-bullying policy nor the proposed other sexual misconduct policy provide for a live hearing in which each party may observe other parties as they present evidence and respond in real time. However, a number of courts have recognized the importance of a meaningful hearing in which the respondent has the opportunity to cross-examine the accuser and adverse witnesses in the presence of a neutral fact-finder.

Further, the Title IX procedures only allow advisors to speak during cross-examination, and the rest of the procedures ban advisors from speaking on behalf of their advisees at any time.

Having an advocate who is permitted to make arguments during proceedings is essential, because not every student is capable of being a strong oral advocate on their own behalf when undergoing this potentially life-altering, and often confusing, process. It is also critical to remember that statements made by students to investigators are not privileged and may be admissible against them in subsequent criminal proceedings; meaning students will have to choose between speaking out to defend themselves in the campus proceeding, or staying silent in order to avoid their words potentially coming back to haunt them should their case go to court.

Harvard promises students freedom of expression and fairness when they’re accused of misconduct. Harvard also promises students an educational atmosphere free from harassment and discrimination. These important goals need not be in tension. By revising the proposed policies to include FIRE’s recommended procedural safeguards, the university can ensure student safety and respect their core rights.

If you’re a member of the Harvard campus community interested in submitting a comment yourself, we encourage you to visit this website and email your thoughts, by tomorrow, to communitymisconductpolicies@harvard.edu.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

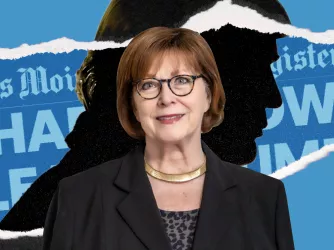

FIRE’s defense of pollster J. Ann Selzer against Donald Trump’s lawsuit is First Amendment 101

China’s censorship goes global — from secret police stations to video games

High schoolers: Become a voice for tomorrow, today!