Table of Contents

Faculty can address Israeli-Palestinian conflict in class assignments, but there are limits

Were the Gaza solidarity encampments erected on college campuses this spring an effective, or even legitimate, form of protest? Is Israel committing genocide in Gaza?

It depends on who you ask. But how, if at all, should faculty handle these questions in class?

The manner in which faculty tackle contested or controversial issues in college classrooms is a source of perennial debate. That debate over preferred pedagogy reignited last month when a nonprofit organization accused a public college in California of violating students’ First Amendment rights based on incidents in which two professors seemingly injected their personal views on hot-button political issues into assigned classwork.

StandWithUs, a pro-Israel nonprofit, wrote Santa Monica College alleging the anti-Israel bias reflected in two professors’ classroom assignments violated students’ First Amendment rights against compelled speech and viewpoint discrimination. The group argued that many students believe they are required to agree with the two professors’ views to successfully pass their courses.

The first incident the letter cites involves a writing exercise professor Ali Ahmadpour assigned in her art history class asking students to adopt the perspective of an art director for a hypothetical pro-Palestinian encampment at SMC. The assignment asked them to explain how they would use “posters, photographs, banners, videos and other creative forms to visually educate the Santa Monica Community” about “the ongoing conflict on [sic] Gaza on the occupied Palestinian lands.”

The second incident occurred in an ethnic studies course in which professor Elias Serna required students to answer the following essay questions: “What are your thoughts on the ongoing destruction and genocide by Israel in Palestine? What forms of protest have you witnessed or observed? What effect does protest have on the political situation in Gaza? What effect is it having on this generation?”

Based on these facts, StandWithUs reasoned:

It is clear from both assignments that Serna and Ahmadpour proceed from the premise that their political opinions are facts that must be unquestioningly accepted by students as they complete their coursework. . . . Here, these professors are requiring students to adopt their opinions (that Israel is engaging in “ongoing destruction and genocide” or occupying stolen lands) and to support the establishment of encampments on SMC grounds. That is constitutionally impermissible.

Is StandWithUs correct? Does it violate students’ First Amendment rights to assign coursework which reflects professors’ own particular viewpoint about a contested issue? More specifically, did Ahmadpour and Serna run afoul of the First Amendment by assigning work in which the existence of an ongoing genocide in Gaza and the righteousness of campus encampments were assumed facts?

The answer, in short, is no, in the absence of evidence that students were required to publicly parrot the professors’ views or suffered retaliation for voicing opposing views.

Based on the facts described by StandWithUs, there is currently insufficient evidence to suggest Ahmadpour and Serna violated the First Amendment. College curricula generally receive the protection afforded by academic freedom — both that of the institution to manage its own academic affairs without unreasonable outside government interference and that of individual professors to teach without unreasonable interference from administrators.

Students, of course, retain their own First Amendment rights. That means instructors cannot require students to express agreement with a particular view or penalize students simply for expressing a different viewpoint. But merely asking students to study or discuss materials with which they disagree as part of their academic coursework, or even asking them to adopt controversial views for purposes of an assignment, is not by itself unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination or compelled speech.

While asking students to take argumentative positions that conform to a teacher’s own views on a hot-button issue may risk discomfiting those with opposing views, it does not by itself violate the First Amendment.

Courts have grappled with these issues most often in the context of religious coursework. There, courts have clearly distinguished teaching about particular religions — including the beliefs and prayers of religions — from requiring students to profess their acceptance of those religious tenets. For example, in 2019 the Fourth Circuit held that asking students to write down the words of a prayer to demonstrate their knowledge of a religion in the context of a high school world history course did not cross a constitutional line. And in a similar analysis of the purpose and effect of quiz questions under the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment, the Ninth Circuit held that a college instructor had qualified immunity against a student’s claims that a quiz disparaged his religion. Because the quiz could be understood to be asking students to demonstrate their knowledge of the material, the court found that the student did not have a “clearly established” right not to be asked such questions. (Nor was one established by this case, as the court did not reach the merits of the claim itself.) On the other hand, some courts have relied on a court precedent from the K–12 context, where schools have greater leeway to regulate student speech, to hold colleges may require students to profess particular beliefs as a condition of their coursework. Last year, the Rhode Island Supreme Court held — based on dubious reasoning — that a student did not have a clearly established right against being required by his social work master’s program to publicly lobby on behalf of views he opposed. And a federal appellate court has held a state university’s acting program could require a student to say words she found offensive as part of acting-class exercises so long as the exercises were pedagogically relevant.

How do these legal principles apply to the incidents at SMC?

Freedom or safety? College admins don’t need to choose.

News

Free speech and a safe campus environment need not conflict. Colleges can safeguard both without compromising either.

First, Ahmadpour’s art history assignment does not require students to profess their personal belief that the Gaza solidarity encampments seen on many campuses this spring are good. The assignment is a thought exercise that asks students to adopt the perspective of a person promoting an encampment at SMC through art and visual media. It is similar to debate or law school classes in which an instructor might randomly assign students to argue on behalf of a particular side without regard to students’ personal beliefs. The point of such an assignment is for a student to learn how to make a case on behalf of a party or cause, not to assert and defend their personal beliefs on the underlying issue. Where Ahmadpour could potentially run afoul of constitutional lines (at least outside of Rhode Island) is if she took the assignment into the “real world” by requiring students to publicly promote a real encampment.

While Ahmadpour’s assignment was explicitly framed as a thought experiment within the confines of the classroom, Serna’s ethnic studies essay question does appear to assume the veracity of the view that Israel is committing a genocide in Gaza. However, although framing that view as an unstated assumption of fact might cause students to feel pressured to accept it, more important to the First Amendment analysis is that the question does not require students to accept Serna’s assumption in their answer. It is an open-ended question, merely asking for students’ thoughts on the issue, followed by questions about students’ observations of protests and the effect of protesting. These are pedagogically relevant questions to assign students in an ethnic studies course, and they are protected by academic freedom. A First Amendment violation would potentially arise only if Serna also retaliated against students for expressing disagreement in their responses. StandWithUs’ letter does not even allege, let alone offer proof, that such retaliation took place.

Professors should — and do — debate how and whether to address personal opinions on controversial issues in the classroom. That’s a worthwhile discussion, with many different views on the wisdom of various approaches. But while asking students to take argumentative positions that conform to a teacher’s own views on a hot-button issue may risk discomfiting those with opposing views, it does not by itself violate the First Amendment.

Academic freedom protects both the professor who carefully avoids revealing their political opinions and the professor who centers their views in their coursework — so long as the professor does not require students to publicly adopt the professor’s views or retaliate against students for offering different perspectives. And, from the information we have, it protects Serna’s and Ahmadpour’s assignments too, whether or not one agrees with the wisdom of their approaches.

FIRE defends the rights of students and faculty members — no matter their views — at public and private universities and colleges in the United States. If you are a student or a faculty member facing investigation or punishment for your speech, submit your case to FIRE today. If you’re faculty member at a public college or university, call the Faculty Legal Defense Fund 24-hour hotline at 254-500-FLDF (3533). If you’re a college journalist facing censorship or a media law question, call the Student Press Freedom Initiative 24-hour hotline at 717-734-SPFI (7734).

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

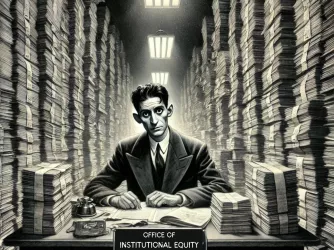

Navigating the Kafkaesque nightmare of Columbia's Office of Institutional Equity

A picture is worth a thousand words — unless a college district bans it

Intimidating abridgments and political stunts — First Amendment News 461