Table of Contents

Court Holds Prosecutor Personally Liable for Unconstitutional Search of Student Who Created a Parody Newsletter

After the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit reaffirmed that "speech, such as parody and rhetorical hyperbole, which cannot reasonably be taken as stating actual fact, enjoys the full protection of the First Amendment," a federal district court in Colorado last week held a deputy district attorney personally liable for an illegal search that she approved to be conducted on the home of a student blogger.

The facts of this case, from a First Amendment perspective, are stunning. Thomas Mink, at the time a student at the University of Northern Colorado (UNC), created an Internet-based newsletter called The Howling Pig (THP). The editor-in-chief of THP was identified in the newsletter as Mr. Junius Puke, a parody of Professor Junius Peake, a finance professor at UNC. Junius Puke was depicted on the blog via a photograph of Professor Peake that was altered to include sunglasses, a small nose, and a small mustache. This parody blog, according to the Student Press Law Center, led to Mink's home being searched, his computer being seized, and his spending a week in jail.

That is because, in 2008, Professor Peake reported to the Colorado police that he believed that he was a victim of criminal libel based on THP's portrayal of the fictitious Junius Puke. Shockingly, under Colorado law, criminal libel is committed when people "knowingly publish or disseminate, either by written instrument, sign, pictures, or the like, any statement or object tending to ... impeach the honesty, integrity, virtue, or reputation or expose the natural defect of one who is alive, and thereby to expose him to public hatred, contempt, or ridicule." That law is so overbroad as to already violate the First Amendment. Mink argued as much, especially because the truth is no defense to the charge that a publisher/writer exposed the natural defects of someone. See C.R.S. §18-13-105. However, the Tenth Circuit ultimately held that Mink lacked standing to challenge the statute as a whole, and, to this day, a violation of Colorado's criminal libel statute carries a penalty of 12 to 18 months.

Professor Peake, embarrassed by the statements on THP's website, used the criminal libel statute to specifically complain to the police about four items: the doctored photograph of Junius Puke; a statement on the website that Puke "gambled in tech stocks" in the 1990s; a statement that, on Wall Street, Puke "managed to luck out and ride the tech bubble of the nineties like a $20 whore and make a fortune"; and the website's inclusion of articles about UNC and Colorado that Professor Peake thought would be attributed to him.

When the police checked out the website, they found a disclaimer noting that "[THP] would like to make sure that there is no possible confusion between our editor Junius Puke and the Monfort D[i]stinguished Professor of Finance, Mr. Junius ‘Jay' Peake." Professor Peake informed the police that this disclaimer had not always been present on the site. Using the power of the state, the police then took steps to identify Mink as THP's true author, and Chief Deputy District Attorney for the Nineteenth Judicial District Susan Knox signed off on a search warrant of the home where Mink lived with his mother. Mink's personal computer was seized during this search.

Mink then filed suit against Knox, arguing that she approved an illegal search of his home in violation of the Fourth Amendment's requirement that searches be supported by probable cause. A federal district judge in Colorado, Judge Lewis T. Babcock, dismissed the suit and held that Knox was entitled to qualified immunity. As we have explained previously with respect to the infamous case of Hayden Barnes at Valdosta State University, qualified immunity protects government officials from suits for monetary damages if they violate an individual's constitutional rights, so long as their acts are not so clearly established as unconstitutional that a reasonable government official would understand that his or her actions were unlawful. Qualified immunity ensures that government officials can perform their functions without having to constantly worry about lawsuits, while still protecting the public from government officials who blatantly violate clearly established constitutional rights.

The Tenth Circuit, on appeal, overruled Judge Babcock's view that Knox deserved qualified immunity and reversed the dismissal of Mink's suit. The Tenth Circuit held that, depending on the facts, Mink may have alleged a search and seizure that was so unlawful, Knox should have known she was violating the Fourth Amendment. The Tenth Circuit based its reasoning on the fact that THP, a parody newsletter, constituted speech that was protected by the First Amendment and therefore could not form the basis of criminal libel. According to the Tenth Circuit, "no reasonable reader would believe that the statements in that context were said by Professor Peake in the guise of Junius Puke, nor would any reasonable person believe that they were statements of fact as opposed to hyperbole or parody." See Mink v. Suthers, 613 F.3d 995, 1009 (10th Cir. 2010). The Tenth Circuit therefore held that Knox violated clearly established law:

Ms. Knox's review of the [A]ffidavit and [W]arrant occurred in December 2003. Long before that, it was clearly established in this circuit that speech, such as parody and rhetorical hyperbole, which cannot reasonably be taken as stating actual fact, enjoys the full protection of the First Amendment and therefore cannot constitute the crime of criminal libel for purposes of a probable cause determination. Moreover, it was also clearly established that warrants must contain probable cause that a specified crime has occurred and meet the particularity requirement of the Fourth Amendment in order to be constitutionally valid.

Back on remand, Judge Babcock considered the facts and several other of Knox's arguments, including the argument that Knox had not properly inspected the proposed search warrant, and found them unconvincing and disingenuous. Judge Babcock therefore entered judgment in favor of Mink on a successful lawsuit, and Knox was held personally liable for her unconstitutional actions. A hearing on damages is forthcoming, the likely end of the eight-year legal battle.

Unfortunately, Colorado's unconstitutional statute is not unique; many states have criminal libel statutes that punish speech that is likely protected under the First Amendment. We hope that the rulings by the Tenth Circuit and Judge Babcock remind prosecutors and college administrators, who often encounter parody websites that they may wish to censor, that the First Amendment clearly protects this type of speech. Overreaching, either by public university administrators or by distracted or overzealous prosecutors, will not be tolerated by the courts when free speech is jeopardized. In Hayden Barnes' case, we hope the Eleventh Circuit follows the Tenth Circuit's reasoning and affirms the denial of qualified immunity against the administrator who punished Barnes for a non-threatening parody collage that was protected political protest.

Although some government officials may wish otherwise, protected speech is called "protected" for a reason. The courts will safeguard it at the financial peril of those who violate the Constitution. Parody cannot be criminalized, and those who create parody cannot be treated as criminals.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

Trump administration’s reasons for detaining Mahmoud Khalil threaten free speech

VICTORY! 9th Circuit rules in favor of professor punished for criticizing college for lowering academic standards

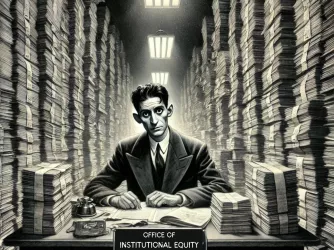

Navigating the Kafkaesque nightmare of Columbia's Office of Institutional Equity