Table of Contents

‘Your words are offensive!’ — ‘Pardon me?’ — The 20th anniversary of Lenny Bruce’s posthumous pardon — First Amendment News 405

Back on Christmas Eve in 2003, the following appeared on the front page of the New York Times:

At the trial level, a New York three-judge criminal court panel convicted Bruce of word crimes (“dirty words”) in a comedy club (the Cafe Au Go Go) in 1964.

In 1965, a state appellate court reversed the conviction of the club’s owner, Howard Solomon. In Bruce’s case, he fled the jurisdiction and died in 1966, before an appeal could be taken. Had he lived, Bruce’s conviction would certainly have been reversed too.

Though his case never went to the U.S. Supreme Court, Bruce’s persecution changed the culture. This was the last time a comedian had been convicted of a word crime when performing in a comedy club.

The posthumous pardon petition

Many years after Bruce’s death, and after publishing “The Trials of Lenny Bruce,” David Skover and I had an idea: Why not seek a posthumous pardon?

We organized a petition campaign replete with a letter of support filed by noted constitutional scholars and First Amendment Lawyers.

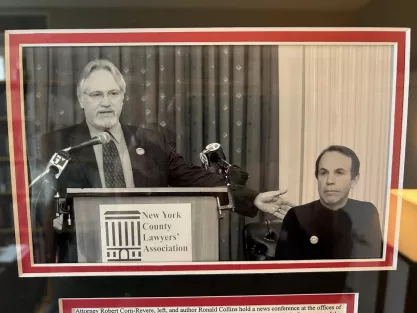

We then set out to find a lawyer to do the legal work pro bono, of course. Bob Corn-Revere agreed to take the case on and did an incredible job. When the petition was filed, we issued a press release and held a press conference in New York.

If truth be known, we really didn't expect a pardon.

The pardon

On Christmas Eve, Bob called me (I was then working at the Newseum) to say that Bruce had been pardoned and that my “phone would soon be ringing off the hook.” And so it was. According to a story in The New York Times:

The governor said the posthumous pardon — the first in the state's history — was “a declaration of New York's commitment to upholding the First Amendment.”

“Freedom of speech is one of the greatest American liberties, and I hope this pardon serves as a reminder of the precious freedoms we are fighting to preserve as we continue to wage the war on terror,” Mr. Pataki said in a statement.

Lenny today

In so many ways, Lenny lives on. Simply consider everything from “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” series to Ronnie Marmo’s Lenny Bruce standup comedy performances titled, “I’m Not a Comedian, I’m Lenny Bruce.”

Speaking of Marmo, see:

- Collins and Marmo, “Comedy clubs are free speech zones — and the antidote to cancel culture,” The McDowell News (April 25)

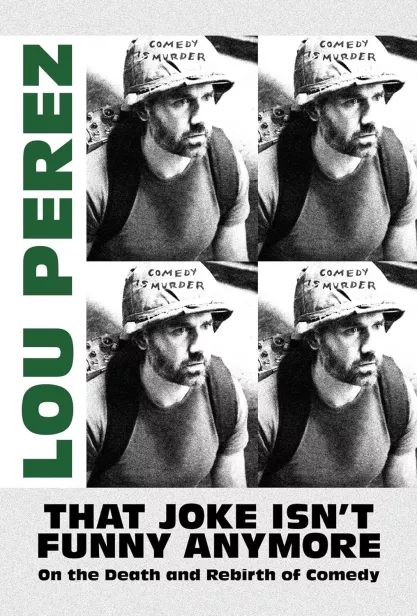

And then there is the work of Lou Perez, comedian and author of “That Joke Isn't Funny Anymore: On the Death and Rebirth of Comedy.”

**** Speaking of Perez, this Saturday he is slated to have a short film piece on the anniversary of the Lenny Bruce pardon. The FIRE-sponsored piece will appear on YouTube, FIRE’s social media, and elsewhere.

Related

- Greg Lukianoff, “The Story Behind The New Documentary ‘Can We Take a Joke?’” FIRE (Aug. 11, 2016)

It started with a comment from a comedian about playing on college campuses.

Last week, we honored the 50th anniversary of the death of the late, great, iconoclastic comedian Lenny Bruce.

As older generations know, but the current one might not, Lenny Bruce was the last comedian in America to be sentenced to jail for jokes he made in a comedy club. Indeed, he was sentenced to four months in jail for telling jokes after midnight at the now-shuttered Cafe au Go Go in New York City. He fled to Los Angeles to avoid serving time. He died of a drug overdose on August 3, 1966 in the middle of an epic court battle to clear his name.

Last week also marks the official release of a documentary, of which I’m an executive producer, called Can We Take a Joke?. The film takes a humorous look at modern “outrage culture” and makes the argument that we can have either great comedy or a “right not to be offended” — we simply can’t have both. It includes interviews with famous comedians like Penn Jillette, Gilbert Gottfried, Adam Carolla, Lisa Lampanelli and Karith Foster, as well as authors Jon Ronson and Jonathan Rauch, who talk about the interrelationship between comedy, free speech, social media, and the culture we create on America’s college campuses.

Forthcoming scholarly article on deepfakes and First Amendment

- Matthew Weiner, “Destined to Deceive: The Need to Regulate Deepfakes with a Foreseeable Harm Standard,” Michigan Law Review (forthcoming)

Political campaigns have always attracted significant attention, and politicians have often been the subjects of controversial — even outlandish — discourse. In the last several years, however, the risk of deception has drastically increased due to the rise of “deepfakes.” Now, practically anyone can make audio-visual media that are both highly believable and highly damaging to a candidate. The threat deepfakes pose to our elections has prompted several states and Congress to seek legislative remedies that ensure recourse for victims and hold bad actors liable.

These recent attempts at deepfake laws are open to attack from two different loci. First, there is a question as to whether these laws unconstitutionally infringe on deepfake creators’ First Amendment rights. Second, some worry that these laws do not adequately protect against the most harmful deepfakes. This Note proposes a new approach to regulating deepfakes. By delineating a “foreseeable harm” standard, with a totality-of-the-circumstances test rather than a patchwork system of discrete elements, this Note addresses both major concerns. Not only is a foreseeable harm standard effective, workable, and constitutionally sound; it is also grounded in existing tort law. Moreover, a recent Supreme Court decision pertaining to false statements and the First Amendment, United States v. Alvarez, lends support to such a standard. Adopting this standard will combat the looming threat of politically oriented deepfakes while preserving the constitutional right to free speech.

Forthcoming scholarly article on copyright, free speech and reimaging works

- Cathay Smith, “Rewriting History: Copyright, Free Speech, & Reimagining Classic Works,” Villanova Law Review (2024)

On February 17, 2023, news broke that Puffin Books, a subsidiary of Penguin Random House and publisher of Roald Dahl’s books, had edited at least ten of Dahl’s classic children’s books to “make them less offensive and more inclusive.” These edits included changing words related to characters’ appearances, race, gender, weight, and mental health, such as removing descriptions of children as “fat,” women as “ugly,” and people as “crazy,” replacing phrases like “the old hag” with “old crow,” and updating “weird African language” so it was no longer “weird.” The public backlash to the news was significant and attracted criticism from several high-profile public figures. But, despite the significant media coverage and public discussion of those announcements, little attention has been paid to any actual legal implications of revising classic books.

This Article offers a comprehensive examination of the copyright and free speech implications of revising classic works, including books, films, and dramatic works. Through extensive research of primary materials and secondary sources outside the legal literature, this Article surveys the history of revising classic children’s books, films, and dramatic works to remove offensive content and make them palatable to modern audiences. It then explores three questions: Do edits to classic children’s works advance social justice or do they rewrite history? Do they censor speech or do they promote copyright’s purpose of encouraging free expression? How do these edits to classic works implicate copyright doctrines of infringement, fair use, and derivative rights? By answering these questions, this Article uncovers potential conflicts between copyright policy, free speech, and social policy, and reimagines copyright’s role in serving the diverse interests of society.

New scholarly article on book bans

- Isabelle Langrock, Jack LaViolette, Marcelo Goncalves, and Katie Spoon, “Book Bans in Political Context: Evidence from U.S. Public Schools,” SSRN (Nov. 28)

In the 2021–2022 school year, more books were banned in U.S. school districts than in any previous year. Book banning and other forms of information censorship have serious implications for democratic processes, and censorship has become a central theme of partisan political rhetoric in the United States. However, there is little empirical work on the exact content, predictors of, and efficacy of this rise in book bans.

Using a comprehensive dataset of 2,532 bans that occurred during the 2021–2022 school year from PEN America, combined with county-level administrative data, multiple book-level digital trace datasets, restricted-use book sales data, and a novel crowd-sourced dataset of author demographic information, we find that (i) banned books are disproportionately written by people of color and feature characters of color, both fictional and historical, in children’s books; (ii) counties that have become less conservative over time are more likely to ban books than neighboring counties; and (iii) national levels of interest in books are largely unaffected after they are banned.

These results suggest that rather than serving as an effective censorship tactic, book banning in this recent U.S. context, targeted at low-interest children’s books featuring diverse characters, is more similar to a symbolic political action to galvanize shrinking voting blocs.

More in the news

- “Trump’s Lawyers Ask Full Appeals Court To Review Gag Order in Election Case,” First Amendment Watch (Dec. 19)

- Joyce Lupiani, “Trump's legal team invokes First Amendment defense to dismiss 2020 election racketeering charges,” Fox News (Dec. 19)

- Mark Goldfeder, “These university presidents need to go back to school on the First Amendment,” Washington Examiner (Dec. 19)

- Eugene Volokh, “Legislators Don't Have First Amendment Right Not to Show Up to Legislature,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Dec. 18)

- “Rudy Giuliani Ordered to Pay $148 Million in Damages to Georgia Election Workers,” First Amendment Watch (Dec. 18)

- “Federal judge upholds Texas’ TikTok ban on state-owned devices,” Free Speech Center (Dec. 13)

- Philip Marcelo, “NRA has surprising defender in its free-speech case at the Supreme Court: the ACLU,” Free Speech Center (Dec. 11)

2022-2023 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Review granted

- Vidal v. Elster (argued Nov. 1)

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier (argued Oct. 31)

- Moody v. NetChoice, LLC / NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton / NetChoice, LLC v. Moody

- National Rifle Association of America v. Vullo

Pending petitions

- Pierre v. Attorney Grievance Commission of Maryland

- Porter v. Martinez

- Brokamp v. James

- Sharpe v. Winterville Police Dept.

- Winterville Police Department v. Sharpe

- Jarrett v. Service Employees International Union Local 503, et al

- Porter v. Board of Trustees of North Carolina State University

- Alaska v. Alaska State Employees Association

- Speech First, Inc. v. Sands

- O’Handley v. Weber

- Tingley v. Ferguson (distributed for conference 7 times as of 11/28/23)

State action

- Lindke v. Freed (argued Oct. 31)

Review denied

- Stein v. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Inc., et al.

- Blankenship v. NBCUniversal, LLC

- Center for Medical Progress v. National Abortion Federation

- Frese v. Formella

- Mazo v. Way

Free speech related

- Miller v. USA (pending) (statutory interpretation of 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c) advocacy, lobbying and protest in connection with congressional proceedings)

Previous regularly scheduled FAN

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE or of Mr. Collins.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

Supreme Court must halt unprecedented TikTok ban to allow review, FIRE argues in new brief to high court

Australia blocks social media for teens while UK mulls blasphemy ban

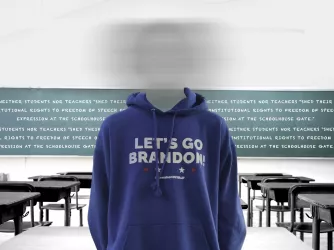

Free speech advocates converge to support FIRE’s ‘Let's Go Brandon’ federal court appeal