Table of Contents

Upside-down Justice – Samuel Alito, ‘Mrs. Alito,’ and the symbolic speech debacle — First Amendment News 424

Thomas P. Costello via Imagn Content Services, LLC

An upside down American flag waves as pro-Trump protestors take over the steps of the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

While the Supreme Court considered an election case, an upside-down flag (now seen as a signal of support for Trump) flew proudly from Justice Samuel Alito’s Alexandria, Virginia, home.

Okay, so he engaged in a little symbolic speech, what’s the big problem? Well, consider what Jodi Kantor reported for The New York Times: “While the flag was up, the court was still contending with whether to hear a 2020 election case, with Justice Alito on the losing end of that decision.”

Smacks of bias? Shocking! No, not possible from a “fair-minded” Supreme Court Justice! Such conduct might violate judicial ethics rules . . . if only the Supreme Court had such enforceable rules.

But it doesn’t. Again, shocking!

Was this display an example of what Chief Justice John Roberts described in the 2015 case Williams-Yulee v. The Florida Bar as unprotected “conduct most likely to undermine public confidence in the integrity of the judiciary”? Seems so. But alas, Justice Alito tendered an explanation: “I had no involvement whatsoever in the flying of the flag,” he said in an emailed statement to The New York Times. “It was briefly placed by Mrs. Alito in response to a neighbor’s use of objectionable and personally insulting language on yard signs.”

Think of it as the “Spousal Defense” (i.e., “the Mrs. did it”): The “Mrs.” in the Alito home wears the pants and thus has complete control over the domain, including what kinds of symbolic expression are displayed. Even if the Justice knew of his wife’s expressive pro-Trump actions, Hell, he may well have no control over such matters. If he did, he might have acted otherwise.

Then again, perhaps not. When Justice Alito blamed his wife for the flying of an upside-down American flag at their home shortly after January 6, late night talk show host Stephen Colbert joked that Alito “dropped a dime on his gal.” Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Dick Durbin told reporters at the time that “he wants Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito to recuse himself” after the news of the upside-down flag broke. However, “Durbin said he doesn’t plan to hold an inquiry.”

And then there was the secret release of the draft of Justice Alito’s Dobbs abortion opinion. Alito said he had a “pretty good idea” who the culprit was, but didn’t name them. Was he suggesting, perchance, that it might have been “Mrs. Alito”? We will never find out, because even after the “full investigation” that Chief Justice Roberts promised, the leaker remains unknown. Worse still, we don’t even know the “full” details of that investigation.

So that’s where things end for now in a Court with no meaningful code of ethics, with no real transparency when it comes to internal investigations, and with self-righteous, black-robed men blaming everyone but themselves for the wrongs plaguing what was once known as the rule of law.

How dead is that ideal these days!

News flash: White House declines to cancel Harrison Butker who slammed Biden

- Daniel Desrochers, “Butker slammed Biden in commencement speech. He’s still invited to the White House,” Kansas City Star (May 17)

Kansas City Chiefs kicker Harrison Butker may have sparked controversy with his commencement speech at Benedictine College recently — but he didn’t jeopardize the Chiefs’ victory trip to the White House. “We invite the entire team and we do that always,” White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said when asked whether the Chiefs are still welcome to visit later this year.

Lambda Legal brings on senior First Amendment lawyer

- “Lambda Legal Announces New Senior Counsel Dedicated to First Amendment Protections” Lambda Legal (May 17)

Kenneth Upton appointed to position made possible with $1 million grant from Alphawood Foundation Chicago

Lambda Legal is proud to announce the appointment of Kenneth Upton as the organization’s inaugural Senior Counsel and First Amendment Strategist, based in the Midwest Regional Office in Chicago. This newly created position was made possible through a generous multiyear grant of $1 million from Alphawood Foundation Chicago to bolster Lambda Legal’s efforts to defend LGBTQ+ rights against the misuse of First Amendment claims and protect America’s separation of church and state.

“We are immensely grateful to Alphawood Foundation Chicago for their support of Kenneth Upton’s vital work,” said Kevin Jennings, CEO of Lambda Legal. “As we face increasing attacks on LGBTQ+ rights under the guise of religious freedom, this gift will allow us to hire our first attorney dedicated to First Amendment protections and strengthen our ability to fight back against discrimination by upholding the constitutional principles of equality and secularism.”

Kenneth Upton joins Lambda Legal after serving for five years as Senior Litigation Counsel for Americans United for Separation of Church and State, where he litigated against religious extremists and their lawmaker allies attacking freedom in America. His work included challenging regulations allowing healthcare providers to refuse care based on religious beliefs, opposing taxpayer funding of discriminatory religious charter schools, and defending policies requiring school clubs not to discriminate against LGBTQ+ students.

“Alphawood Foundation Chicago is thrilled to support the new Senior Counsel position and Lambda Legal’s work defending the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals and families,” said Chirag Badlani, Executive Director. “We are grateful Kenneth has rejoined Lambda Legal’s Midwest Regional Office in Chicago and will use his experience to protect the First Amendment rights of the LGBTQ+ community and all those living with HIV.”

Prior to his recent return, Upton spent over 13 years–from 2005 to 2018–at Lambda Legal’s South Central Regional Office in Dallas, Texas, where he appeared in more than fifty cases involving issues such as marriage equality, parental rights, workplace discrimination, and HIV discrimination. He has served on the governing council of the LGBT Law Section of the State Bar of Texas and received the Norman W. Black Award in recognition of his significant contributions to LGBTQ+ legal issues.

“I am honored to rejoin Lambda Legal and grateful to Alphawood Foundation Chicago,” said Kenneth Upton. “This gift will enable us to mount a more robust defense against those who seek to weaponize the First Amendment to undermine and erode and LGBTQ+ rights and freedom for all Americans.”

Assange wins right to appeal extradition order

- “WikiLeaks Founder Assange Wins Right to Appeal Against an Extradition Order to the US,” Free Speech Center (May 20)

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange can appeal against extradition to the United States on espionage charges, a London court ruled Monday — a decision likely to further drag out an already long legal saga.

High Court judges Victoria Sharp and Jeremy Johnson ruled for Assange after his lawyers argued that the U.S. government provided “blatantly inadequate” assurances that he would have the same free speech protections as an American citizen if extradited from Britain.

Assange, 52, has been indicted on 17 espionage charges and one charge of computer misuse over his website’s publication of a trove of classified U.S. documents almost 15 years ago. Hundreds of supporters cheered and applauded outside court as news of the ruling reached them from inside the Royal Courts of Justice. Assange’s wife, Stella, said the U.S. had tried to put “lipstick on a pig — but the judges did not buy it.” She said the U.S. should “read the situation” and drop the case. “As a family we are relieved but how long can this go on?” she said. “This case is shameful and it is taking an enormous toll on Julian.”

Kaminski and Jones on AI Speech

- Margot E. Kaminski and Meg Leta Jones, “Constructing AI Speech,” Yale Law Journal Forum (2024)

Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems such as ChatGPT can now produce convincingly human speech, at scale. It is tempting to ask whether such AI-generated content “disrupts” the law. That, we claim, is the wrong question. It characterizes the law as inherently reactive, rather than proactive, and fails to reveal how what may look like “disruption” in one area of the law is business as usual in another. We challenge the prevailing notion that technology inherently disrupts law, proposing instead that law and technology co-construct each other in a dynamic interplay reflective of societal priorities and political power. This Essay instead deploys and expounds upon the method of “legal construction of technology.” By removing the blinders of technological determinism and instead performing legal construction of technology, legal scholars and policymakers can more effectively ensure that the integration of AI systems into society aligns with key values and legal principles.

Legal construction of technology, as we perform it, consists of examining the ways in which the law’s objects, values, and institutions constitute legal sensemaking of new uses of technology. For example, the First Amendment governs “speech” and “speakers” toward a number of theoretical goals, largely through the court system. This leads to a particular set of puzzles, such as the fact that AI systems are not human speakers with human intent. But other areas of the law construct AI systems very differently. Content-moderation law regulates communications platforms and networks toward the goals of balancing harms against free speech and innovation; risk regulation, increasingly being deployed to regulate AI systems, regulates risky complex systems toward the ends of mitigating both physical and dignitary harms; and consumer-protection law regulates businesses and consumers toward the goals of maintaining fair and efficient markets. In none of these other legal constructions of AI is AI’s lack of human intent a problem.

By going through each example in turn, this Essay aims to demonstrate the benefits of looking at AI-generated content through the lens of legal construction of technology, instead of asking whether the technology disrupts the law. We aim, too, to convince policymakers and scholars of the benefits of the method: it is descriptively accurate, yields concrete policy revelations, and can in practice be deeply empowering for policymakers and scholars alike. AI systems do not in some abstract sense disrupt the law. Under a values-driven rather than technology-driven approach to technology policy, the law can do far more than just react.

Volokh on Delaware ruling on speech integral to criminal conduct exception

- Eugene Volokh, “Delaware Court on the First Amendment Exception to ‘Speech Integral to Criminal Conduct’,” The Volokh Conspiracy (May 19)

“Some courts have incorrectly used this exception to rationalize upholding a statute that criminalizes speech . . . simply because their legislature passed a law labeling it criminal. The limited line of United States Supreme Court cases that have addressed this exception in no way supports such a broad reading.”

Friday's decision in State v. Reeves, decided by Judge Jeffrey Clark (Del. Super. Ct.), evaluates the Delaware stalking law under which he or she (1) "threatens, or communicates to or about another" on 3 or more separate occasions, (2) in a manner that would cause a reasonable person to fear for their safety or experience significant mental anguish or distress.

The court concluded that the statute would be unconstitutional as applied to certain contexts:

[T]he Statute would enable the prosecution of a doctor who tells a patient on at least three occasions that, although an operation may be necessary to save the patient's life, the effect of the operation will cause accompanying physical pain or injury. Likewise, the Statute would criminalize three complaints by a restaurant's customer on social media about poor service at the restaurant, that in turn, causes the owner severe mental anguish because his business failed as a result. The Statute would also criminalize when a person posts critical comments about another, at least three times, on social media when those comments would reasonably cause significant mental distress to another.

[ . . . ]

And the court had this to say about the state's argument that the law was constitutional because it only applied to "speech integral to criminal conduct":

In broad terms, the State seeks to characterize [the statute] as falling under [the] {speech integral to criminal conduct} exception in its entirety.

[ . . . ]

As an overview, the speech integral to criminal conduct exception is not as broad as the State contends. Nor is it an antidote, in and of itself, to Mr. Reeves’ facial challenge. Typically, this exception has been limited to criminal conduct such as bribery, extortion, conspiracy, or the solicitation of others to commit a separate crime. For example, there is no First Amendment violation when the government prosecutes a defendant based upon a statement such as "pay me money, or I will report you for a crime." Nor is there First Amendment protection for a defendant's statement to a law enforcement officer offering money to avoid arrest. The speech in those examples is integral to criminal conduct in the same way as is speech used to extort or solicit another to commit a crime. Such speech deserves no First Amendment protection.

[ . . . ]

Some courts have incorrectly used this exception to rationalize upholding a statute that criminalizes speech . . . simply because their legislature passed a law labeling it criminal. The limited line of United States Supreme Court cases that have addressed this exception in no way supports such a broad reading.

New book on military censorship in WWII

- Molly Guptilling Manning, “The War of Words: How America's GI Journalists Battled Censorship and Propaganda to Help Win World War II,” Blackstone Publishing (Sept. 26)

From The New York Times bestselling author Molly Guptill Manning comes The War of Words, the captivating story of how American troops in World War II wielded pens to tell their own stories as they made history.

At a time when civilian periodicals faced strict censorship, US Army Chief of Staff George Marshall won the support of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to create an expansive troop-newspaper program. Both Marshall and FDR recognized that there was a second struggle taking place outside the battlefields of World War II--the war of words. While Hitler inundated the globe with propaganda, morale across the US Army dwindled. As the Axis blurred the lines between truth and fiction, the best defense was for American troops to bring the truth into focus by writing it down and disseminating it themselves.

By war's end, over 4,600 unique GI publications had been printed around the world. In newsprint, troops made sense of their hardships, losses, and reasons for fighting. These newspapers--by and for the troops--became the heart and soul of a unit.

From Normandy to the shores of Japan, American soldiers exercised a level of free speech the military had never known nor would again. It was an extraordinary chapter in American democracy and military history. In the war for "four freedoms," it was remarkably fitting that troops fought not only with guns but with their pens. This stunning volume includes fourteen pages of photographs and illustrations.

New scholarly article on social media and consumer protection

Jake B. Lake, “Labels, Social Media, Consumer Protection, and the First Amendment,” Florida Law Review Forum (Jan. 23)

Labels matter. For decades, Internet companies such as Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) have benefitted from First Amendment protection by invoking the label “free speech” to defend their content, including material they receive from others. Companion cases from Texas and Florida, both currently before the U.S. Supreme Court, could turn on whether the justices apply a different label: “commercial speech.” Like beer drinkers debating whether Miller Lite is less filling or tastes great, the justices will decide whether Facebook is more speech or more commerce.

Affixing the “commercial speech” tag to Internet platforms’ content would be significant because states seeking to regulate Internet companies have turned to and built upon laws regulating commerce — namely, state statutes that provide civil remedies in response to deceptive and unfair trade practices. The potential for conflict between consumer protection laws and First Amendment rights has been recognized for decades. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court in 1990 considered a Federal Trade Commission complaint concerning a boycott by criminal defense lawyers seeking higher pay. The lawyers claimed the First Amendment protected their boycott; the Supreme Court disagreed.6 Such conflicts between regulations of commerce and the First Amendment have also arisen more recently in the Supreme Court and in the lower courts.

The litigation concerning the Texas and Florida social media laws presents similar issues. If those states’ laws are applied to Internet companies as commercial speakers subject to consumer protection laws, First Amendment protections of their speech will be less rigorous, leaving more room for the regulations that Texas and Florida lawmakers have imposed. If Internet platforms’ content is seen as non-commercial speech, the laws would face strict scrutiny — unless, that is, the justices apply another label: “common carrier.” In upholding the Texas law, Fifth Circuit Judge Oldham found Internet platforms are common carriers, such as ferries, railroads, or telegraph and telephone companies.8 The Eleventh Circuit disagreed.9 If the Supreme Court agrees with Judge Oldham and applies the “common carrier” label to Internet platforms, that designation will allow states to impose tighter rules on the platforms, including limits on standards platforms set on their customers’ speech.

New scholarly article on the First Amendment and trademark practices

- Stacey L. Dogan and Jessica M. Silbey, “Jack Daniel’s and the Unfulfilled Promise of Trademark Use,” Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal (May 17)

In Jack Daniel’s v. VIP Products, the Supreme Court announced a bright-line rule: whatever speech protections govern the use of trademarks in artistic works, no such rule applies “when an alleged infringer uses a trademark in the way the Lanham Act most cares about: as a designation of source for the infringer’s own goods.” Those who engage in “trademark use,” in other words, must face the usual likelihood-of-confusion standard, regardless of whether their use also has expressive dimensions. The Jack Daniel’s defendant conceded that it was engaged in trademark use, so the opinion did not do the hard work of distinguishing between trademark use and non-trademark use. And its failure to do so has begun to wreak havoc in the lower courts.

This essay makes three small but hopefully clarifying points to help lower courts apply the rule announced in Jack Daniel’s. First, it examines the relationship between Jack Daniel’s and Rogers v. Grimaldi, which the Court did not repudiate but treated as a prototypical example of non-trademark use. Under Jack Daniel’s, uses of marks in expressive works are not ordinarily trademark uses, contrary to some recent lower court decisions. Second, drawing from hints in Jack Daniel’s, we find that the Court contemplates a bounded notion of trademark use that reflects the language and the normative goals of the Lanham Act. Finally, we close with some suggestions, again drawing on Jack Daniel’s itself, on how to tame the likelihood-of-confusion test to protect expressive speech.

New scholarly article on curtailing protests

- Alireza Nourani-Dargiri, “The Universal Effort to Curtail Protests,” University of Louisville Law Review (May 20)

Protesting is an internationally recognized right that has had a significant impact on the world. Recognizing its importance, governments and nongovernment institutions have set out to codify, promote, and protect protest rights, claiming they value its expression. Unfortunately, those laws and policies may just be empty words as protest rights around the world are regularly infringed on, particularly in a biased manner. At an alarming rate, protesters face life-altering, disastrous consequences if they wish to express this human right — rights countries simultaneously claim to be “supremely precious in our society.” This concerted effort against protesting makes its “free” expression nearly impossible for the average person, reserving this human right for those privileged enough to afford the, sometimes literal, costs.

This paper aims to describe the universal effort to curtail protest rights through defining the contradiction between how we purport to treat these rights, and how we actually treat them. Because this inconsistency threatens the validity of these rights, this article offers how we should treat protests to maintain its legitimacy.

Amicus brief re occupational speech

- Benjamin Field and Arif Panju, “Amicus Brief of Institute for Justice in Texas Department of Insurance v. Stonewater Roofing (Supreme Court of Texas),” SSRN (May 17)

This is the amicus brief of the Institute for Justice in Texas Department of Insurance v. Stonewater Roofing before the Supreme Court of Texas. It argues that occupational speech is fully protected by the First Amendment and that content-based regulations on roofers' and contractors' speech must satisfy heightened scrutiny.

FIRE’s Free Speech Dispatch

- Sarah McLaughlin, “How court rulings in Hong Kong and Australia threaten the global internet,” FIRE (May 16)

This year, FIRE launched the Free Speech Dispatch, a regular series covering new and continuing censorship trends and challenges around the world. Our goal is to help readers better understand the global context of free expression. The previous entry addressed a series of troubling censorship allegations across Europe, extensive online restrictions in China, and Iran’s campaign against its critics. Today, we’ll look at the global implications of online censorship in Hong Kong and Australia, a flurry of blasphemy and lèse-majesté arrests, and more.

Hong Kong banned a protest anthem. How will global tech companies respond? The outlook for free expression in Hong Kong has looked dire in recent years, and a new ruling further cements the city’s decline into deepening repression. Last week, a Hong Kong appeals court granted a government request to ban the protest anthem “Glory to Hong Kong,” reversing a previous ruling from a lower court. Three appellate judges called the song a “weapon” against national security and argued that an injunction was “necessary” to pressure tech companies to take down recordings and adaptations of the song.

China’s foreign ministry spokesman Lin Jian also claimed the ruling was a “necessary move” to fulfill Hong Kong’s “constitutional responsibility of safeguarding national security and the dignity of the national anthem.”

The implications for free expression in Hong Kong are deeply troubling, but what remains to be seen is what the ruling means for global tech companies — and for their users worldwide.

More in the news

- Laurie Kellman and Jocelyn Geck, “Israel-Hamas war testing whether campuses are sacrosanct places for speech, protest,” Free Speech Center (May 20)

- Eugene Volokh, “No Pseudonymity for Student Challenging University Discipline in Non-Sexual-Assault/Harassment Case,” The Volokh Conspiracy (May 20)

- “Trump Asks New York’s High Court To Intervene in Fight Over Gag Order,” First Amendment Watch (May 16)

- Haleluya Hadero, “TikTok content creators sue U.S. over law that could ban platform,” Free Speech Center (May 15)

- Bobby Allyn, “Legal experts say a TikTok ban without specific evidence violates the First Amendment,” NPR (May 14)

2023-2024 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Cases Decided

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier

- Speech First, Inc. v. Sands (certiorari granted, judgment re the bias policy claims vacated, and case remanded to the Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit with instructions to dismiss those claims as moot) (Thomas and Alito, dissenting)

Review granted

- Vidal v. Elster (argued Nov. 1)

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier (decided March 15, see below under “State Action”)

- Moody v. NetChoice, LLC and NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton (argued Feb. 26)

- National Rifle Association of America v. Vullo (argued March 18)

- Murthy v Missouri (argued March 18)

- Gonzalez v. Trevino (argued March 20)

Pending petitions

- No on E, San Franciscans Opposing the Affordable Care Housing Production Act, et al. v. Chiu

- Pierre v. Attorney Grievance Commission of Maryland

- O’Handley v. Weber

State action

- Lindke v. Freed (Barrett, J., 9-0: “The state-action doctrine requires Lindke to show that Freed (1) had actual authority to speak on behalf of the State on a particular matter, and (2) purported to exercise that authority in the relevant posts. To the extent that this test differs from the one applied by the Sixth Circuit, we vacate its judgment and remand the case for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.”)

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier (Per Curiam: 9-0: “We granted certiorari in this case and in Lindke v. Freed (2024), to resolve a Circuit split about how to identify state action in the context of public officials using social media. Because the approach that the Ninth Circuit applied is different from the one we have elaborated in Lindke, we vacate the judgment below and remand the case to the Ninth Circuit for further proceedings consistent with our opinion in that case.”)

Review denied

- Mckesson v. Doe (Separate statement by Sotomayor, J.)

- Brokamp v. James

- Griffin v. HM Florida-ORL (application for stay denied)

- M. C. v. Indiana Department of Child Services

- Spectrum et al v. Wendler

- Porter v. Martinez

- Molina v. Book

- Porter v. Board of Trustees of North Carolina State University

- NetChoice, LLC v. Moody

- Alaska v. Alaska State Employees Association

- X Corp. v. Garland

- Tingley v. Ferguson (Justice Kavanaugh would grant the petition for a writ of certiorari. Justice Thomas, dissenting from the denial of certiorari. (separate opinion) Justice Alito, dissenting from the denial of certiorari. (separate opinion))

- Jarrett v. Service Employees International Union Local 503, et al

- Sharpe v. Winterville Police Dept.

- Winterville Police Department v. Sharpe

- Stein v. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Inc., et al.

- Blankenship v. NBCUniversal, LLC

- Center for Medical Progress v. National Abortion Federation

- Frese v. Formella

- Mazo v. Way

Free speech related

- Miller v. United States (pending) (statutory interpretation of 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c) advocacy, lobbying and protest in connection with congressional proceedings) // See also Fischer v. United States (argued April 16)

Last scheduled FAN

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE or Mr. Collins.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

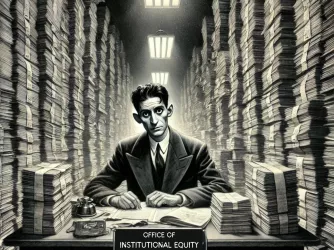

Navigating the Kafkaesque nightmare of Columbia's Office of Institutional Equity

A picture is worth a thousand words — unless a college district bans it

Intimidating abridgments and political stunts — First Amendment News 461