Table of Contents

Free Speech in (college) crisis times: Thoughts and resources — First Amendment News 421

First Amendment News is a weekly blog and newsletter about free expression issues by Ronald K. L. Collins. It is editorially independent from FIRE.

The recent protests occurring on college campuses represent another one of those pinpoints in time — the kind that prompt us to pause and reflect upon the role of the First Amendment in our culture and our discourse.

The First Amendment was meant for crisis times that test our souls. It was designed to be vibrant in moments of conflict, when the urge for censorship is great. It calls on us to be tolerant when toleration wars with our repressive instincts. That, at least, is the ideal. That ideal is also a necessity if the coin of the Madisonian guarantee is to have meaningful value.

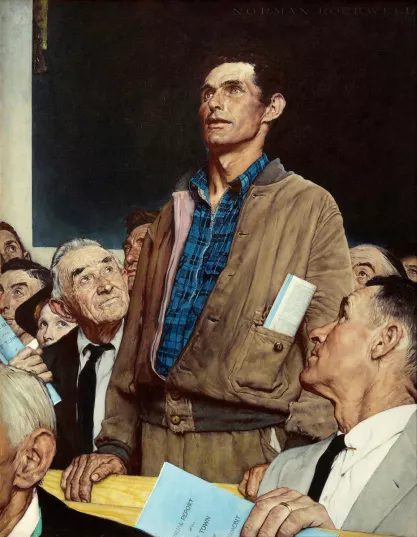

If the First Amendment did not have any staying power when ideological conflict was near its boiling point, what purpose would it serve? Wouldn’t it be a mere parchment freedom? After all, we don’t need a First Amendment to protect speech that offends none — the kind of guarantee that makes for an idealized Norman Rockwell painting sans any practical grit. Rather, we need that man on the canvas to inspire the liberty-loving impulse sometimes striving to survive.

Yes, the First Amendment is about testing limits. If you doubt it, reread Justice Brandeis’ powerful dissent in Whitney v. California:

“Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards.”

Indeed, they were not. They exalted freedom even when it came with a high cost.

In a constitutional evolutionary sense, when the First Amendment is applied robustly its freedoms inevitably rearrange the boundaries of the norms of the past. The current conflicts on college campuses over the safety of Israel and the plight of those in Gaza are most assuredly topics worthy of hardy debate. Compelled silence in the face of such conflicts is the trademark of tyranny. So let the debate unfold.

Still, there are limits; there are exceptions; and there are time, place, and manner requirements. The First Amendment is not a license for anarchy and criminal conduct. The very idea of a democratic constitution is antithetical to lawlessness. Yet, some — the violently self-righteous — act as if only their so-called rights and viewpoints matter. As they see it, opposing views need to be squashed. By their logic, if the government will not censor their opponents, then they will. Lawlessness in the name of free speech is no virtue . . . unless, like the civil rights protestors of the past, one is willing to accept punishment for their transgressions.

The name for such behavior is “civil disobedience.”

Two other points merit consideration: First, in crisis times there will always be excesses, such as government overreach and/or discriminatory enforcement. This is exactly the time when the First Amendment needs to do its work. Second — and this is not a legal point but an educational one: while the First Amendment stands to protect rights, its uninhibited exercise in the college student setting may sometimes conflict with the educational mission of a school. Ideally, the two missions would be in sync with one another. At other times, they may not — even though there is a First Amendment right to engage in a particular kind of protest. In other words, the educational concerns of a school are not perforce synonymous with the liberties exercised in the public square.

Rights are not a cost-free game. If we haven’t learned that already, we’re going to have to learn it now.

FIRE’s Alex Morey on campus free speech

- Jake Tapper, “College protests raise legal questions around free speech,” CNN (April 30)

Noteworthy quotes

Erwin Chemerinsky, “No One Has a Right to Protest in My Home,” (April 26)

[T]he rancorous debate over the Israel-Hamas war seems to be blurring some people’s sense of which settings are public and which are not. Until recently, neither my wife — Catherine Fisk, a UC Berkeley law professor — nor I ever imagined a moment when our right to limit a protest at a dinner held at our own home would become the subject of any controversy.

Jessie Appleby, “FIRE Letter to University of Texas at Austin,” FIRE (April 25)

FIRE is deeply concerned by the University of Texas at Austin’s outrageous and unnecessary use of riot police yesterday afternoon to forcibly disperse students and faculty engaged in a peaceful Gaza solidarity walk-out on campus, taking journalists covering the event with them. UT Austin, at the direction of Governor Greg Abbott, appears to have preemptively banned peaceful pro-Palestinian protesters due solely to their views rather than for any actionable misconduct. UT Austin’s inexcusable actions violate its binding First Amendment obligations as a public university, as well as its obligations under state law to keep all open, outdoor areas of public campuses free for all constitutionally protected protest. UT Austin must ensure all criminal trespassing charges against peaceful protesters are dropped, if not already dismissed, and forgo further pursuit of institutional or criminal punishment.

Suggested guidelines

Anthony Romero and David Cole, “Open Letter to College and University Presidents on Student Protests,” ACLU (April 26)

- Schools must not single out particular viewpoints for censorship, discipline, or disproportionate punishment;

- Schools must protect students from discriminatory harassment and violence;

- Schools can announce and enforce reasonable content-neutral protest policies but they must leave ample room for students to express themselves;

- Schools must recognize that armed police on campus can endanger students and are a measure of last resort; and

- Schools must resist the pressures placed on them by politicians seeking to exploit campus tensions.

What forms of protest are not protected?

“Here’s what students need to know about protesting on campus right now,” FIRE (April 25)

The First Amendment does not protect unlawful conduct. If you engage in conduct while protesting that violates the law — such as violence, assault, vandalism, or underage drinking — you can face arrest and/or campus disciplinary proceedings. Other unprotected conduct (including speech) that can lead to arrest or disciplinary action includes:

- True threats and intimidation

- Incitement

- Discriminatory harassment

- Substantially disrupting events or deplatforming speakers

For a more detailed explanation of the First Amendment’s boundaries, see “As campuses reel, a reminder of the First Amendment’s boundaries,” by FIRE Legal Director Will Creeley.

Recent agreement between Northwestern University and pro-Palestinian protesters

Northwestern commits to the following:

- Free Speech

- The University will permit peaceful demonstrations on Deering Meadow through the end of spring quarter classes (June 1) provided all such activity immediately and continuously complies with University policies. The university will allow one aid tent to remain on Deering Meadow. All other tents at Deering Meadow must be removed.

- Any devices used to project or amplify sound must be approved in advance. The University commits to considering these requests in good faith.

- Only Northwestern students, faculty, and staff will be allowed in the demonstration area, except if otherwise authorized by the University.

- The University and student representatives will work to maintain safety and ensure participation in the demonstration area is limited to University community members and allows for other reserved events to occur on Deering Meadow. Participants may be asked by the University to show their Wildcard ID.

- The above applies to Deering Meadow. All other demonstrations on campus must also comply with University policies.

- The University will publicly condemn the doxing of any community member and will advise employers not to rescind job offers for students engaging in speech protected by the First Amendment.

Need clarification as to what doxxing means? We can help.

Volokh and Bambauer on college free speech

- Eugene Volokh, “Free Speech Unmuted: Free Speech on Campus,” Free Speech Unmuted (April 30)

When can colleges and universities discipline students based on the content of their speech? When can they impose content-neutral restrictions on the time, place, and manner of demonstrations? Given that the First Amendment applies only to government operations, what rules apply to private institutions?

Forthcoming book by Cass Sunstein on campus free speech

- Cass Sunstein, “Campus Free Speech: A Pocket Guide” Harvard University Press (Sept. 2024)

From renowned legal scholar Cass R. Sunstein, a concise, case-by-case guide to resolving free-speech dilemmas at colleges and universities.

Free speech is indispensable on college campuses: allowing varied views and frank exchanges of opinion is a core component of the educational enterprise and the pursuit of truth. But free speech does not mean a free-for-all. The First Amendment prohibits “abridging the freedom of speech,” yet laws against perjury or bribery, for example, are still constitutional. In the same way, valuing freedom of speech does not stop a university from regulating speech when doing so is necessary for its educational mission. So where is the dividing line? How can we distinguish reasonable restrictions from impermissible infringement?

In this pragmatic, no-nonsense explainer, Cass Sunstein takes us through a wide range of scenarios involving students, professors, and administrators. He discusses why it’s consistent with the First Amendment to punish students who shout down a speaker, but not those who chant offensive slogans; why a professor cannot be fired for writing a politically charged op-ed, yet a university might legitimately consider an applicant’s political views when deciding whether to hire her. He explains why private universities are not legally bound by the First Amendment yet should, in most cases, look to follow it. And he addresses the thorny question of whether a university should officially take sides on public issues or deliberately keep the institution outside the fray.

At a time when universities are assailed on free-speech grounds from both left and right, Campus Free Speech: A Pocket Guide is an indispensable resource for cutting through the noise and understanding the key issues animating the debates.

‘So to Speak’ podcast webinar on free speech and campus unrest

- “Campus unrest - live webinar,” FIRE (April 30)

Host Nico Perrino joins his FIRE colleagues Will Creeley and Alex Morey to answer questions about the recent campus unrest and its First Amendment implications.

Flashback: Chemerinsky on campus free speech

- “Chemerinsky: Navigating free speech on campus,” University of Tulsa (Feb. 27)

On Feb. 1, The University of Tulsa’s College of Law hosted Erwin Chemerinsky, a renowned constitutional law authority, as the keynote speaker at the annual John W. Hager Distinguished Lecture in Law. Attendees from different parts of the region gathered to hear Chemerinsky discuss the intricate nature of free speech on college campuses.

[ . . . ]

Chemerinsky delivered a compelling and timely address on the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. Although the subject matter was specifically designed for a university audience, the principles discussed were applicable and relevant across a wide range of applications. The dean of UC Berkeley Law delivered a captivating thesis recognizing how higher education encourages the exchange of diverse and sometimes conflicting perspectives. He also stressed that the U.S. Constitution safeguards the right to express any viewpoint or idea without fear of government repression.

Post on free speech rights of K-12 students

- Robert Post, “Managing Student Expression: A Constitutional Theory of Student Free Speech Rights,” SSRN (March 27)

Courts and commentators write as if the speech of K-12 students were endowed with full First Amendment protection, save in narrow circumstances when it is reasonably foreseeable that the speech will cause substantial disruption or materially interfere with the rights of others, when it is vulgar or lewd, when it involves school sponsored communication, or when it advocates for illegal drug use. But even the most superficial observation of student classroom expression reveals the fictional nature of this perspective. Student speech in classrooms is comprehensively and routinely subject to forms of regulation that violate the most elementary rules of what the Court has called “ordinary First Amendment standards.” Student classroom speech is controlled by official discretion; it is compelled; it is constrained by content and viewpoint discrimination; it is subject to prior restraints.

The goal of this article is to offer a constitutional account of student speech that can explain the contours of its actual regulation. Ordinary First Amendment standards are designed to protect participation in what the Court has called “the market of public opinion.” This market must remain perpetually free from state control so that, in the Court’s words, government authority can “be controlled by public opinion, not public opinion by authority.” The goal is to ensure that the state remain continuously responsive to “that public opinion which is the final source of government in a democratic state.”

Often government responds to popular will by creating institutions charged with implementing specific tasks. Government creates courts to apply justice or agencies to administer the social security system. It would be counterproductive in such circumstances to insist on the open-endedness that ordinary First Amendment standards are designed to protect. Instead mission-driven state institutions must effectively control the speech of those within the scope of their authority so that they can achieve their assigned objectives.

K-12 schools are mission-driven institutions of this kind. They are created to educate students. They are therefore empowered to regulate student speech to achieve the objective of education. Courts debate the nature of this objective. Case law reveals at least three different conceptions of the constitutional objective of education. The paper denominates these as democratic education, civic education, and critical education. Each distinct account of the educational mission of schools implies a different structure for the regulation of student speech. Courts also differ about whether courts should defer to school regulation of student speech or instead whether they should scrutinize it using independent judicial review. Much can be learned about the actual geography of student speech rights by systematically exploring the implications of these basic distinctions.

The article also evaluates how courts conceive the nature, scope, and force of school managerial authority. That authority receives highly deferential review insofar as students seek to speak qua students. But insofar as students seek to speak qua citizens, the paper assesses the variables and doctrine used by courts to weigh the prerogatives of school managerial authority against the free speech rights of students. Of particular concern in the past several years has been the efforts of schools to control off-campus student speech that might potentially undermine school functioning.

The paper argues that the general framework of speech regulation within managerial government organizations offers a coherent, consistent, and convincing way to explain the complexities of our actual constitutional jurisprudence of student speech. It seeks to substitute that cogent perspective for the fictional appeals to fictional rights that too often dominate contemporary scholarly and judicial discussion of student speech.

SCOTUS denies review in Musk social media case

- “Supreme Court rejects Musk appeal over social media posts that must be approved by Tesla,” Free Speech Center (April 30)

The Supreme Court on April 29 rejected an appeal from Elon Musk over a settlement with securities regulators that requires him to get approval in advance of some social media posts that relate to Tesla, the electric vehicle company he leads.

The justices did not comment in leaving in place lower-court rulings against Musk, who complained that the requirement amounts to “prior restraint” on his speech in violation of the First Amendment.

The case stems from messages Musk posted on Twitter in 2018 in which he claimed he had secured funding to take Tesla private. The tweets caused the company’s share price to jump and led to a temporary halt in trading.

Forthcoming book by Helen Norton

- Helen Norton, “Advanced Introduction to US First Amendment Law,” Elgar Advanced Introductions series (Forthcoming, July 28)

Elgar Advanced Introductions are stimulating and thoughtful introductions to major fields in the social sciences, business and law, expertly written by the world’s leading scholars. Designed to be accessible yet rigorous, they offer concise and lucid surveys of the substantive and policy issues associated with discrete subject areas.

This Advanced Introduction discusses the scope of US First Amendment law, considering the available tools and approaches for thinking about constitutional problems involving the government’s regulation of speech, religion, and more. Focusing specifically on the First Amendment as interpreted by the US Supreme Court, it explores the evolution and implementation of the doctrine regarding the freedoms of speech, press, petition, assembly, association, and religion.

More in the news

- “Protesters Take Over Columbia University Building in Escalation of Campus Demonstrations,” First Amendment Watch (April 30)

- Anders Hagstrom, Bradford Betz, Landon Mion, and Chris Pandolfo, “Universities crack down on anti-Israel agitators as protesters call for 'amnesty',” Fox News (April 30)

- “Judge Holds Trump in Contempt, Fines Him $9K, Raises Threat of Jail in Hush Money Trial,” First Amendment Watch (April 30)

- Eugene Volokh, “Alleged ‘QAnon John’’s Libel Lawsuit Against Anti-Defamation League Can Go Forward,” The Volokh Conspiracy (April 30)

- Eugene Volokh, “If He Did Not Want to Be Called a 'Rioter,' Plaintiff Should Not Have Admitted … to 'Participation in … [a] Riot',” The Volokh Conspiracy (April 30)

- Ali Harb, “US advocacy groups back Palestine solidarity campus protests amid Gaza war,” Aljazeera (April 29)

- Talia Barnes, “Freedom or safety? College admins don’t need to choose,” FIRE (April 29)

- “Judge Acquits Lacey on 50 Counts,” Front Page Confidential (April 29)

2023-2024 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Cases Decided

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier

- Speech First, Inc. v. Sands (certiorari granted, judgment re the bias policy claims vacated, and case remanded to the Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit with instructions to dismiss those claims as moot) (Thomas and Alito, dissenting)

Review granted

- Vidal v. Elster (argued Nov. 1)

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier

- Moody v. NetChoice, LLC and NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton (argued: Feb. 26)

- National Rifle Association of America v. Vullo (argued: March 18)

- Murthy v Missouri (argued: March 18)

- Gonzalez v. Trevino (argued: March 20)

Pending petitions

- No on E, San Franciscans Opposing the Affordable Care Housing Production Act, et al. v. Chiu

- Pierre v. Attorney Grievance Commission of Maryland

- O’Handley v. Weber

State action

- Lindke v. Freed (Barrett, J., 9-0: “The state-action doctrine requires Lindke to show that Freed (1) had actual authority to speak on behalf of the State on a particular matter, and (2) purported to exercise that authority in the relevant posts. To the extent that this test differs from the one applied by the Sixth Circuit, we vacate its judgment and remand the case for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.”)

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier (Per Curiam: 9-0: “We granted certiorari in this case and in Lindke v. Freed (2024), to resolve a Circuit split about how to identify state action in the context of public officials using social media. Because the approach that the Ninth Circuit applied is different from the one we have elaborated in Lindke, we vacate the judgment below and remand the case to the Ninth Circuit for further proceedings consistent with our opinion in that case.”)

Review denied

- Mckesson v. Doe (Separate statement by Sotomayor, J.)

- Brokamp v. James

- Griffin v. HM Florida-ORL (application for stay denied)

- M. C. v. Indiana Department of Child Services

- Spectrum et al v. Wendler

- Porter v. Martinez

- Molina v. Book

- Porter v. Board of Trustees of North Carolina State University

- NetChoice, LLC v. Moody

- Alaska v. Alaska State Employees Association

- X Corp. v. Garland

- Tingley v. Ferguson (Justice Kavanaugh would grant the petition for a writ of certiorari. Justice Thomas, dissenting from the denial of certiorari. (separate opinion) Justice Alito, dissenting from the denial of certiorari. (separate opinion))

- Jarrett v. Service Employees International Union Local 503, et al

- Sharpe v. Winterville Police Dept.

- Winterville Police Department v. Sharpe

- Stein v. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Inc., et al.

- Blankenship v. NBCUniversal, LLC

- Center for Medical Progress v. National Abortion Federation

- Frese v. Formella

- Mazo v. Way

Free speech related

- Miller v. United States (pending) (statutory interpretation of 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c) advocacy, lobbying and protest in connection with congressional proceedings) // See also Fischer v. United States (argued: April 16)

Previous regularly scheduled FAN

FAN 420: “Back into the FIRE: Hasen’s response to FIRE and Rohde: Don’t read the press clause out of the Constitution.”

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE or Mr. Collins.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

Can the government ban controversial public holiday displays?

The trouble with banning Fizz

FIRE's 2025 impact in court, on campus, and in our culture