Table of Contents

Would censorship have stopped the rise of the Nazis? Part 16 of answers to arguments against free speech from Nadine Strossen and Greg Lukianoff

WATCH VIDEO: Would hate speech laws have stopped the Nazis?

In May 2021, I published a list of “Answers to 12 Bad Anti-Free Speech Arguments” with our friends over at Areo. The great Nadine Strossen — former president of the ACLU from 1991 to 2008, and one of the foremost experts on freedom of speech alive today — saw the series and offered to provide her own answers to some important misconceptions about freedom of speech. My answers, when applicable, appear beside hers.

Earlier in the series:

- Part 1: Free speech does not equal violence

- Part 2: Free speech is for everyone

- Part 3: Hate speech laws backfire

- Part 4: Free speech is bigger than the First Amendment

- Part 5: You can shout ‘fire’ in a burning theater

- Part 6: Is free speech outdated?

- Part 7: Does free speech assume words are harmless?

- Part 8: Is free speech just a conservative talking point?

- Part 9: Free speech fosters cultural diversity

- Part 10: Why 'civility' should not trump free expression

- Part 11: ‘New’ justifications for censorship are never really new

- Part 12: Free speech isn’t free with a carveout for blasphemy

- Part 13: Does free speech lead inevitably to truth?

- Part 14: Shouting down speakers is mob censorship

- Part 15: Is counterspeech the best answer to bad speech?

Greg Lukianoff: Given the recent panic over what Elon Musk buying Twitter may mean for hate speech regulation on the platform, I thought it would be important to explain that arguments for hate speech codes are deeply flawed. As we have previously argued in this series, hate speech laws have proven to backfire in predictable and unpredictable ways. In this and a future entry, we’ll be addressing oft-cited arguments that hate speech laws would have prevented historical atrocities.

Assertion: The rise of Hitler and Nazism in Germany is an instructive example of why we should censor hateful and extremist speech.

Greg Lukianoff: Richard Delgado, an early champion of speech codes and now more famous as a founding scholar in the field of Critical Race Theory, cites the Rwandan genocide (more on this in a future entry), along with Weimar Germany, as cautionary tales against free-speech purism. The problem is that neither historical precedent supports the idea that speech restraints could have prevented a genocide.

As I explained in my review of Eric Berkowitz’s excellent book, “Dangerous Ideas: A Brief History of Censorship in the West, from the Ancients to Fake News,” Weimar Germany had laws banning hateful speech (particularly hateful speech directed at Jews), and top Nazis including Joseph Goebbels, Theodor Fritsch and Julius Streicher actually were sentenced to prison time for violating them. The efforts of the Weimar Republic to suppress the speech of the Nazis are so well known in academic circles that one professor has described the idea that speech restrictions would have stopped the Nazis as “the Weimar Fallacy.”

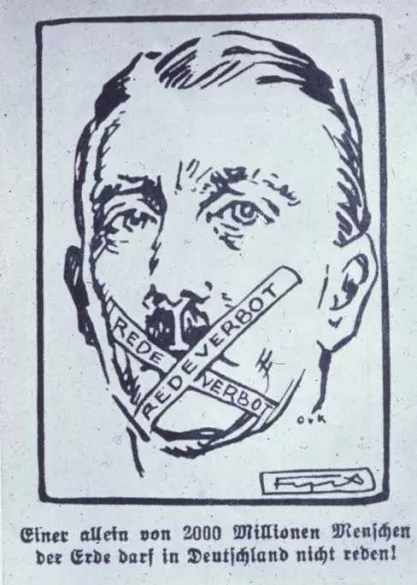

A 1922 law passed in response to violent political agitators such as the Nazis permitted Weimar authorities to censor press criticism of the government and advocacy of violence. This was followed by a number of emergency decrees expanding the power to censor newspapers. The Weimar Republic not only shut down hundreds of Nazi newspapers — in a two-year period, they shut down 99 in Prussia alone — but they accelerated that crackdown on speech as the Nazis ascended to power. Hitler himself was banned from speaking in several German states from 1925 until 1927.

Far from being an impediment to the spread of National Socialist ideology, Hitler and the Nazis used the attempts to suppress their speech as public relations coups. The party waved the ban like a bloody shirt to claim they were being targeted for exposing the international conspiracy to suppress “true” Germans. As one poster explained:

Why is Adolf Hitler not allowed to speak? Because he is ruthless in uncovering the rulers of the German economy, the international bank Jews and their lackeys, the Democrats, Marxists, Jesuits, and Free Masons! Because he wants to free the workers from the domination of big money!

Considering the Nazi movement’s core ideology, as espoused by Hitler in “Mein Kampf,” rested on an alleged conspiracy between Jews and their sympathizers in government to politically disempower Aryan Germans, it is not surprising that the Nazis were able to spin government censorship into propaganda victories and seeming confirmation of their claims that they were speaking truth to power, and that power was aligned against them.

Indeed, censorship that was employed ineffectively to stop the rise of the Nazis was a boon to the Nazis when it came to consolidating their power. The laws mentioned earlier that allowed Weimar authorities to shut down newspapers, and additional laws intended to limit the spread of Nazi ideology via the radio, had their reins turned over to the Nazi party when Hitler became chancellor. Predictably, the Nazis used these preexisting means of censorship to crush any political speech opposing them, allowing for an absolute grip on the country that would have been much more difficult or impossible with strong legal protections for press and speech.

So policing Nazi speech was tried and factually did not avert the rise of the Nazis. Does that mean there was no way to stop the Nazis? The rise of Hitler and the Nazis wasn’t inevitable — there were likely a few historical off-ramps. Hitler’s niece, who had been living with him, and with whom he had been rumored to be in a romantic relationship, was found dead with a gunshot wound in her lung. The death was not seriously investigated before being declared a suicide, but it is not hard to imagine that had this been investigated or become a scandal, it could have stopped Hitler’s personal ascent.

The main and most obvious path that would have averted the rise of the Nazi party would have been the aggressive, or even just proportionate, prosecution of the political violence by the Nazi party before they had seized power.

In 1923, the government of Bavaria banned large public meetings of the Nazi party. In response, inspired by Mussolini’s march on Rome, Hitler and over 600 of his compatriots, including other future leaders of the Nazi party, attempted a violent coup in Munich, involving a firefight that led to the deaths of four police officers and 16 Nazi party members. Afterward, Hilter was tried and convicted for high treason.

Ultimately, it was a permissive attitude towards violence and the degradation of the rule of law that led to the greatest atrocity in history.

He was given, for the crime of a deadly attempted overthrow of the government, an absurdly lenient sentence of only five years — of which he served a total of eight months, during which he wrote “Mein Kampf” before being released on good behavior. The only other person sentenced for the coup, Rudolf Hess, was also sentenced to five years and, like Hitler, only served eight months. Similarly, other instances of political violence committed by Nazis went under-punished when they were punished at all, owing to the sympathy afforded to them by judges and juries that was not afforded to their leftist and communist counterparts.

It should not require the benefit of hindsight to understand that this was a grave error. For leading a deadly attempted overthrow of the government, by the standards of the time, Hitler should have been executed, given life in prison, or at the very least, permanently banned from holding public office.

Restrictions on speech failed to stop the Nazis and ultimately proved to be strong weapons in their hands. Ultimately, it was a permissive attitude towards violence and the degradation of the rule of law that led to the greatest atrocity in history.

For much greater detail on this, listen to this episode of Jacob Mchangama’s FIRE-sponsored podcast, “Clear and Present Danger,” on Weimar Germany and the rise of Hitler.

Greg’s Note: I’d like to recognize FIRE Research Programs Coordinator Ryne Weiss, for his help with this article. His contributions to this series as a whole have been indispensable, but he went especially above and beyond for this piece.

Nadine Strossen: Given the horrors of the Holocaust, even diehard free speech stalwarts would support “hate speech” laws if they would have averted that atrocity. That is certainly the case for me, as the daughter of a German-born Holocaust survivor, who nearly died at Buchenwald. That also is true for international human rights champion Aryeh Neier, who escaped from Nazi Germany as a child with his immediate family, while the Nazis slaughtered his extended family. Neier was the ACLU’s executive director in 1977–78, when the ACLU successfully defended the First Amendment rights of neo-Nazis to demonstrate in Skokie, Illinois, a town that had a large Jewish population, many of whom were — or were closely related to — Holocaust survivors. Because he is a renowned free speech absolutist, readers will be surprised to learn that Neier has said that he would support hate speech laws if they would have forestalled Nazism:

I am unwilling to put anything, even love of free speech, ahead of detestation of the Nazis. . . . I could not bring myself to advocate freedom of speech in Skokie if I did not believe that the chances are best for preventing a repetition of the Holocaust in a society where every incursion on freedom is resisted. Freedom has its risks. Suppression of freedom, I believe, is a sure prescription for disaster.

Proponents of hate speech laws assume that the enforcement of such laws might have prevented the spread of Nazi ideology in Germany, but the historical record belies this assumption. Throughout the Nazis’ rise to power, there were laws on the books criminalizing hateful, discriminatory speech, which were similar to contemporary hate speech laws. As noted by Alan Borovoy, general counsel of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, when he explained his/the CCLA’s opposition to Canada’s current hate speech legislation:

Remarkably, pre-Hitler Germany had laws very much like the Canadian anti-hate law. Moreover, those laws were enforced with some vigour. During the fifteen years before Hitler came to power, there were more than two hundred prosecutions based on anti-Semitic speech. And, in the opinion of the leading Jewish organization [in Germany] of that era, no more than 10% of the cases were mishandled by the authorities.

The German hate speech laws were enforced even against leading Nazis, some of whom served substantial prison terms. But rather than suppressing the Nazis’ anti-Semitic ideology, these prosecutions helped the Nazis gain attention and support. For example, Danish journalist Flemming Rose reports that between 1923 and 1933, the virulently anti-Semitic newspaper, Der Stürmer, published by Julius Streicher, “was either confiscated or [its] editors [were] taken to court on . . . thirty-six occasions.” Yet, “[t]he more charges Streicher faced, the greater became the admiration of his supporters. The courts became an important platform for Streicher’s campaign against the Jews.”

The major problem with Germany’s response to rising Nazism was not that the Nazis enjoyed too much free speech, but that the Nazis literally got away with murder. In effect, they stole free speech from everyone else, including anti-Nazis, Jews, and other minorities. As Aryeh Neier commented in his classic book about the Skokie case: “The lesson of Germany in the 1920s is that a free society cannot be . . . maintained if it will not act . . . forcefully to punish political violence. It is as if no effort had been made in the United States to punish the murderers of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr. . . . and . . . other victims” of violence during the civil rights movement.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

The American people fact-checked their government

Facing mass protests, Iran relies on familiar tools of state violence and internet blackouts

Unsealed records reveal officials targeted Khalil, Ozturk, Mahdawi solely for protected speech