Table of Contents

‘Coddling’ the Afterword Part 5: International Coddling

Jon and Greg wrote an afterword for “The Coddling of the American Mind” in the summer of 2021 to be added to a second edition of the book in 2022, but it grew so long that it would have raised the page count and cost of the book substantially. Instead, the nine sections of the afterword will be released in seven parts in the coming weeks, here and at Persuasion.

- Part 1: Gen Z’s Mental Health Continues to Deteriorate

- Part 2: It’s Social Media — More Than Screen Time — That Matters for Mental Health

- Part 3: Increasing Persecution on Campus

- Part 4: The Polarization Spiral and the Great Awokening (published at Persuasion)

- Part 5: International Coddling

- Part 6: Corporate Coddling (published at Persuasion)

When we published our Atlantic article in August of 2015, many critics said we were cherry picking a few anecdotes from a handful of elite American universities. They said we were exaggerating, perhaps even catastrophizing. But in fact, the problems we described there and in this book have spread very rapidly since 2018 in two directions: out from the USA to many other countries; and out from campus into the workplace. These trends had already hit K-12 education, and K-12 may have been ground zero, or patient zero, for the trends in the first place — as Greg was quoted in a recent Atlantic article by Olga Khazan. Greg said that around 2013-2014 a critical mass of students were showing up to campus already believing what we dubbed "the three great untruths.” We cover the last two trends – K-12 and the workplace – in the next two installments of this afterword. This post is devoted to the international pandemic of untruth.

Our Atlantic article and our book were titled The Coddling of the American Mind, but within a year it was clear that nearly identical dynamics were emerging in the UK, Canada, and Australia. In all three countries, childhood freedom dropped precipitously in the 1990s or early 2000s and “concierge parenting” became common. A 2021 study of nearly 2000 British parents found that their children were not allowed to play unsupervised outside until they were nearly 11, while the parents themselves recalled having such freedom by the time they turned 9. The lead researcher lamented the fact that British children were not getting “enough opportunities to develop their ability to assess and manage risk independently,” and she feared that this might “have an impact on their mental health and overall wellbeing.”

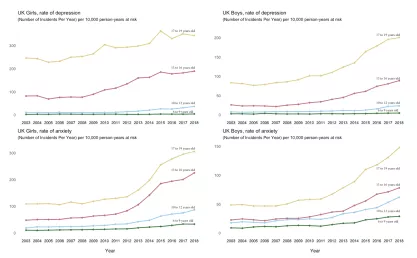

Just as in the USA, rates of depression, anxiety, and self-harm began to rise in the 2010s in all of the major English speaking countries as the oldest members of Gen Z became teenagers and then headed off to college. Changes in teen suicide rates were more variable.

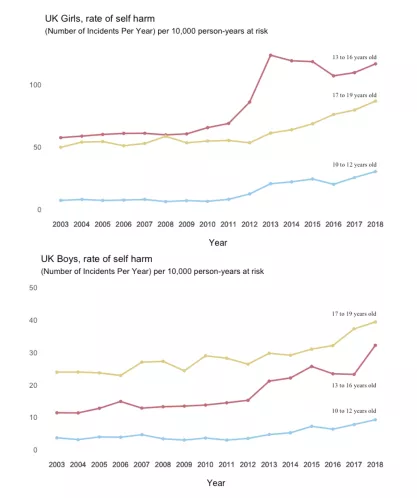

The graphs are just as shocking as those we showed for American adolescents in Chapter 7. Here are the trends in the UK, derived from analyses of medical records for a cohort of 9 million children and teens, from Cybulski et al. (2021).

As in the USA we see an elbow — a sharp upturn that begins around 2012 or 2013, that hits both sexes, and that is larger and sharper for girls. The trends for self-harm are even more horrific, and, as in the USA, the rise happens only for girls. (Jon believes that the sudden international rise in self-harm that hits girls around 2013 was caused in large part by the fact that their social lives moved onto Instagram in the two years prior; he’ll have an article on that out later this month.)

And, just as in the USA, this more anxious generation approached their university educations in a more defensive mindset than had the Millennials before them. Words, books, speakers, and even hand gestures came to be seen as harmful — sometimes even as “violence.” For example: in 2017, the student union at one of the Oxford colleges banned the Christian Union from having a table at an activities fair for first year students. A leader of the student union justified the ban in language that indicates endorsement of all three of the great untruths: “there is potential for harm to freshers who are already struggling to feel welcome in Oxford.”

The idea here was that Christianity is associated with colonialism, homophobia, and oppression, so if fragile freshmen merely see a Christian table, they might experience negative emotions, which they might interpret to mean that they are not wanted.

To take a more recent example, Kathleen Stock at the University of Sussex resigned her professorship after years of sustained campaigning by students for her firing, including protests, anonymous flyering, and social media excoriation including threats of violence — all due to Stock’s opposition to gender self-ID and statement that “many trans women are still males with male genitalia, many are sexually attracted to females, and they should not be in places where females undress or sleep in a completely unrestricted way.”

While the resignation, though regretful, may not be surprising, the university’s response to the resignation was a too-rare pleasant surprise. The Vice Chancellor of Sussex issued a statement expressing regret, stating “We had hoped that Professor Stock would feel able to return to work, and we would have supported her to do so . . . Rigorous academic challenge is welcome. However, we have seen an intolerance of her as a member of our community because of her work. This is now - and will always be - in direct opposition to even the most basic principles of academia.”

We encourage you to compare the statement from Sussex with those that followed Bright Sheng stepping down at University of Michigan following his display of a 1965 version of Othello that included blackface. (Sheng’s case thankfully resolved in his favor on Oct. 19 thanks to the efforts of FIRE legal network and Faculty Legal Defense Fund attorney David Nacht).

Also in the UK, this week a Cambridge University debate society banned a historian for satrically mimicking Hitler (the second scenario we have seen this year of a fact pattern that mirrors the plot to the popular Netflix dramedy The Chair), and bragged it was creating a blacklist of speakers never to be invited back that it would share with other groups. In Canada, the Canadian Association of University Teachers censured the University of Toronto for rescinding a job offer from Valentina Azarova, allegedly following donor opposition to Azarova’s pro-Palestinian views. A professor in Australia lost a four-year legal fight following his termination from James Cook University for challenging the scientific consensus on climate change. In New Zealand, a University of Auckland professor faced a gag order and lengthy investigation for criticizing the ties between China and New Zealand universities. Each of these cases is uncannily similar to the sort that we see in the United States.

When Jon visited universities in Australia in 2019, he found all the same trends, just with a several year delay. Aussie parents were increasingly keeping their kids indoors, over-supervised, and protected from small risks (such as climbing trees or playing contact sports). Those kids were increasingly turning into anxious and depressed teens, and those teens were showing up at universities more keen than before to protest speakers and request trigger warnings. (More here.) (Kiwis seem to be doing a better job of raising free range kids, but their universities are suffering many of the same problems we wrote about in Coddling.)

What about the rest of the world? Is it immune, or is it just a few years behind the English-speaking countries? We have not found a good international assessment of teen mental health with data going back before 2010, but Jon and Jean Twenge conducted an analysis of a long-running international educational survey and found a global increase in feelings of loneliness at school since 2012.

Smartphones, social media, and the internet more generally have supercharged the populist and revolutionary movements described by Martin Gurri, leading to greater political instability and anger in many Western democracies. Some of this anger is being expressed on college campuses around the world, where students seem increasingly willing to shout down or de-platform visiting speakers whose messages or associations contradict their political beliefs. See here for multiple examples from Spain.

Many of the ideas about identity, race, gender, and intersectionality that were developed on American college campuses have spread beyond the English speaking world since 2018. In October 2020, French President Emmanuel Macron gave a speech warning about the dangers of “separatism” and urging a renewal of France’s traditional commitment to secularism and assimilation. He lamented the influence of “Anglo-Saxon traditions” and the effects of “social science theories imported directly from the United States.” A few weeks later, after a horrific beheading of a teacher, a debate erupted as to whether left-wing intellectuals were creating conditions that encouraged the spread of Islamist violence. The minister of education charged that some intellectuals and their “indigenist, racialist, and ‘decolonial’ ideologies” that were “imported from North American Campuses” were partly responsible for the violence.

What is happening in non-Western countries? We don’t know yet, but we are trying to find out. In fact, we have set up a page on our website to collect information about “international coddling.” There we have links to Google docs with a standard structure in which we invite residents of those countries to add links to studies and news articles about changes in parenting, rising anxiety/depression, callout-culture on campus, and political polarization — the toxic brew of trends that have severely damaged Gen Z and universities in the USA. Here is the list of Google docs. If you live in any of these countries, we invite you to visit the doc and add information, especially if you have information that disconfirms our hypothesis that the American disease of safetyism is spreading globally.

- The Coddling of the British Mind (the mental health data is already covered in this google doc)

- The Coddling of the Spanish Mind

- The Coddling of the European Mind (for all European countries other than Spain and the UK)

- The Coddling of the Canadian Mind

- The Coddling of the Australian Mind

- The Coddling of the Kiwi Mind

- The Coddling of the Chinese Mind

- The Coddling of the Japanese Mind

- The Coddling of the Korean Mind

In conclusion, we are seeing signs that some of the trends we described in this book are spreading internationally. If we publish a second edition, we could certainly retitle it The Coddling of the English Speaking Mind. We could probably retitle it The Coddling of the Western Mind. And, when we learn more about how the rising middle classes in Asia, Latin America, and Africa raise their children, we might even need to call it The Coddling of the Human Mind in Societies that Become Prosperous and Physically Safe.

Next week: Part 6: Corporate Coddling

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

LAWSUIT: Ex-cop sues after spending 37 days in jail for sharing meme following Charlie Kirk murder

‘Let them sue’: Iowa lawmakers scoffed at First Amendment in wake of Charlie Kirk shooting, records show

City Club of Cleveland rejects illiberal calls to disinvite speaker