Table of Contents

Are younger faculty really more tolerant of unpopular opinions than older faculty?

Shutterstock.com

Cancel Culture is getting worse. As FIRE President and CEO Greg Lukianoff has pointed out many times, more college faculty have been fired during the nine-and-a-half years (and counting) of Cancel Culture, which FIRE defines as roughly starting in 2014 and accelerating past 2017, than lost their jobs during the Red Scare of the 1950s. But who is driving this anti-speech trend on college campuses?

One recent study has pinned the blame on older faculty, but FIRE has its doubts.

The European Consortium for Political Research, an organization founded in 1970 that expands and supports the research of political scientists, recently published its second World of Political Science Survey in collaboration with the International Political Science Association and Pippa Norris, a political science lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School.

This survey samples political scientists from countries all over the world, collecting information on how they feel about their jobs, their experiences with Cancel Culture, the diversity of their colleagues, and the changes they have witnessed in the field in the last five years. This well-rounded study reveals how free speech and academic freedom have evolved within the field of political science.

However, a recent presentation of the data gives us cause for concern.

Free speech among young scholars

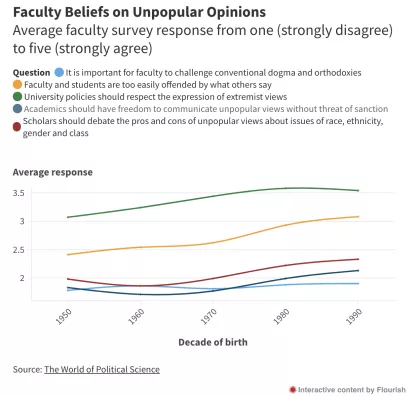

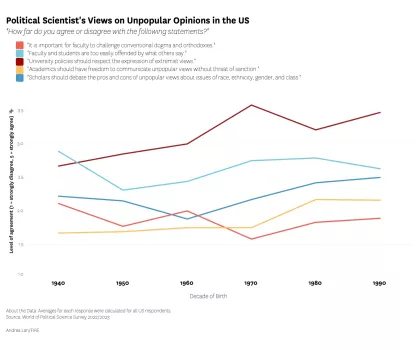

Norris summarized the results of the survey in an article for The Harvard Crimson, “Young Scholars Are Not the Enemies of Free Speech on Campus,” where she argued that, when compared to their older colleagues, “younger faculty were more favorable towards academic free speech, not less, when asked whether it was important to challenge conventional dogma, whether university policies should respect extremist views, and whether scholars should debate unpopular views about identity politics.”

So, are younger faculty — or, rather, younger political science faculty — really more supportive of free speech on campus than their older peers? A closer inspection of the graph above, cited by Norris, suggests her conclusion may not be warranted.

Each question on the graph uses a five-point response scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with 3 being neither agree nor disagree. Examining the graph reveals a frightening discovery — the only statement with which a clear majority of younger political science faculty agreed was: “University policies should respect the expression of extremist views.” This statement focuses on the support for free speech in the abstract, which a majority of academics around the word typically support.

NEW POLL: Americans continue to hold conflicting views about faculty speech rights

A new poll finds that Americans hold deeply conflicting views about free speech on campus — wanting colleges and universities to uphold free speech principles while supporting restrictions of student and faculty expression.

But a majority of younger (and older) political science faculty disagreed with each of the following less abstract statements:

- Scholars should debate the pros and cons of unpopular views about issues of race, ethnicity, gender and class.

- It is important for faculty to challenge conventional dogma and orthodoxies.

- Academics should have freedom to communicate unpopular views without threat of sanction.

These are not results to be excited about. Frankly, they are terrifying. They show that political scientists, both young and old, across the world are not only intolerant of controversial views, but are also opposed to what has long been considered a core practice in the academy — the challenging of conventional ideas.

And if one focuses solely on the Americans who were surveyed, one will come to the frightening realization that these values are lacking among political scientists right here in the U.S.

It is important for the advancement of research for scholars and students to freely debate contentious subjects, and if political scientists disagree on the fundamentals of free speech, then research in the field of political science is doomed.

It is also important to note that the survey sampled political scientists in higher education, not general faculty members. Harkening back to the title and framing of the report of these results in The Harvard Crimson, it is misleading to conflate what young political scientists think with what young scholars overall think.

Each discipline within academia may approach and view free speech and academic freedom differently, and these differences should not be ignored. For example, additional analyses of FIRE’s national survey of U.S. faculty suggest that faculty in business and STEM fields are more likely to support free speech than faculty in other fields.

Where will we be as a society if there’s no critical thinking, no analysis, no debate, if we all just toe the party line and have to repress what we believe?

Faculty members are increasingly facing political intolerance that threatens their reputations, careers, and livelihood, and existing research suggests that the primary sources of this intolerance are younger faculty and graduate students, not older faculty. This is concerning because as faculty retire and leave the academy, younger faculty and graduate students are set to take their place. If younger faculty and graduate students continue to hold anti-free speech values, these values will become embedded in the curriculum and campus environment, potentially exacerbating censorship issues in higher education. Furthermore, restrictions on communication in political research can influence academic work and, in turn, negatively impact the governmental policies being developed using this research.

The results of the WPS survey are interesting, but it’s unfortunate that Norris’s interpretations of the survey data do not match what the data actually shows. In fact, the data seems to indicate that young political science faculty are the opposite of stalwart defenders of free speech.

This raises an important question asked last year by Greg Scholtz, director of the Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure, and Governance for the American Association of University Professors: “Where will we be as a society if there’s no critical thinking, no analysis, no debate, if we all just toe the party line and have to repress what we believe?”

Thankfully, for faculty who are targeted or punished for their speech or scholarship, FIRE has a Faculty Legal Defense Fund that provides “first responder” assistance to protect the freedom of expression and academic freedom of faculty members at public institutions.

Much more work needs to be done, and FIRE is here to help.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

FIRE's 2025 impact in court, on campus, and in our culture

The trouble with banning Fizz

VICTORY: Court vindicates professor investigated for parodying university’s ‘land acknowledgment’ on syllabus