Table of Contents

Free Speech in High School

Why is free speech in schools important?

In four landmark cases, the Supreme Court of the United States has provided a general outline of the First Amendment rights of high school students. Taken together, these four cases give public high school officials more leeway to regulate speech than public college administrators, although some states have passed laws to provide additional protection for free speech in schools. If the Supreme Court’s boundaries for high schoolers’ First Amendment rights were applied to the university setting, the effect on freedom of speech would be substantial. Fortunately, the Court has never held that the limitations on expression allowed in high school cases would pass constitutional muster at public universities.

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969)

Is there free speech for students?

After becoming aware of a plan among some students to protest the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands during school hours, school officials in Des Moines, Iowa, specifically banned wearing armbands in their schools. Previously, students had been allowed to wear “buttons relating to national political campaigns, and some even wore the Iron Cross, traditionally a symbol of Nazism.” The students wore the armbands in violation of the new policy, were suspended, and subsequently sued.

In the Supreme Court case Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the school district claimed that it feared the protest would cause a disruption at school, but it could point to no concrete evidence that such a disruption would occur or ever had occurred as a result of similar protests. The Supreme Court held: “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The Court affirmed that symbolic speech enjoys First Amendment protection, that students possess constitutional rights in public schools, and that “an undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance” is not enough to limit expressive rights. Additionally, the Supreme Court held that the protest did not seriously disturb learning or order at the school and that the ban on armbands “did not purport to prohibit the wearing of all symbols of political or controversial significance” but instead singled out these students’ particular viewpoint.

In declaring the regulation unconstitutional, the Court stated: “[U]ndifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance is not enough to overcome the right to freedom of expression.”

Since Tinker, the regulation of student speech (in public high schools) is generally permissible only when the school reasonably fears that the speech will substantially disrupt or interfere with the operation of the school or the rights of other students. However, Tinker was not the final word on student speech in public high schools.

Learn more about this case by watching FIRE’s interview with Mary Beth Tinker, the namesake of the Tinker decision.

Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986)

In Fraser, a high school student was suspended for giving a speech at a school assembly that included a number of sexual innuendos and double entendres. Prior to the assembly, several teachers warned the student against giving the speech because of the inappropriate content. The Court upheld the suspension, saying: "The schools, as instruments of the state, may determine that the essential lessons of civil, mature conduct cannot be conveyed in a school that tolerates lewd, indecent, or offensive speech and conduct such as that indulged in by this confused boy."

According to Fraser, there is no First Amendment violation when a school punishes, on a viewpoint-neutral basis, a student for “lewd,” “vulgar,” “indecent,” and “plainly offensive” speech during classes, assemblies, or other times when students are forced to listen.

Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988)

Three former editors of the Spectrum, a student newspaper run as part of a journalism class and funded by the Board of Educators in Hazelwood School District, sued after the principal removed two articles from the May 1983 issue that described student experiences with pregnancy and divorce. The principal believed that the students interviewed and parents discussed in the articles could be identified and found the discussions of birth control and sexual activity inappropriate for younger students.

In Hazelwood, the Court upheld a school principal’s decision to delete the stories before they appeared in the student newspaper. The Court reasoned that the publication of the school newspaper, which was written and edited as part of a journalism class, was a part of the curriculum and a regular classroom activity. It wrote: “[E]ducators do not offend the First Amendment by exercising editorial control over the style and content of student speech in school-sponsored expressive activities so long as their actions are reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns.”

Morse v. Frederick (2007)

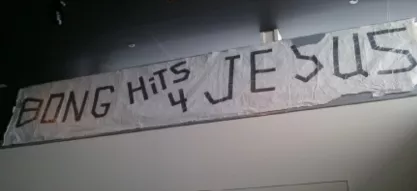

Student Joseph Frederick held up a sign that read "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" at a school-sponsored event. The public school's principal, Deborah Morse, took Frederick's sign and suspended him for 10 days. In Morse, the Supreme Court found that a public high school did not violate the First Amendment rights of the student. Determining that it could “discern no meaningful distinction between celebrating illegal drug use in the midst of fellow students and outright advocacy or promotion,” the Court found that public high schools may “restrict student speech at a school event, when that speech is reasonably viewed as promoting illegal drug use.”

In need of First Amendment resources for teachers? The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression has you covered. Our "First Things First" First Amendment textbook for college undergraduates explores the fundamentals of modern American free speech law. Meanwhile, our K-12 First Amendment curriculum modules help educators enrich and supplement their existing instruction on First Amendment and freedom of expression issues in middle and high school classrooms. Explore thefire.org for even more First Amendment educational resources.