Table of Contents

Disinvitation Season: Protected Counter-Speech or Heckler’s Veto?

It's graduation season again, and as expected, not all of the commencement speakers invited to speak at universities' ceremonies manage to make it to the stage. Earlier this month, FIRE reported on Morehouse College squeezing Rev. Dr. Kevin R. Johnson out of the commencement speaker lineup following critical comments he had made about President Obama, and several other speakers have withdrawn from graduation events after student objections over their views.

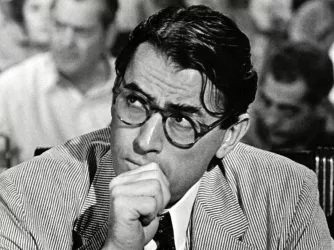

As FIRE President Greg Lukianoff told The New York Times for an article published yesterday, "It does appear that 'disinvitation season' incidents have accelerated in recent years, with this year inspiring an uptick of these episodes."

"These episodes" can include everything from protesters on campus, to online petitions asking schools to disinvite speakers, to students physically blocking speakers from the event's venue. So when are university community members engaging in counter-speech—protected by the First Amendment—and when are they censoring viewpoints with which they disagree?

That depends on whether protesters actively prevent the speaker's voice from being heard. For example, this past Saturday, students at the University of California, Berkeley protested Attorney General Eric Holder's speech at the law school, holding signs and even commissioning an airplane to fly a banner objecting to the Department of Justice's handling of state marijuana laws. But Holder was able to address the graduating class nonetheless, and students were able to hear both Holder's speech and that of students who disagree with him. This is commendable.

In many instances, though, speakers are unable to give their addresses as planned. The result is often that a vocal viewpoint (even if it represents a minority on campus) is heard instead of the viewpoint of a commencement invitee. This outcome runs contrary to what should be universities' ultimate goal of facilitating more speech, and is the kind of protest that amounts to censorship. For example, as the Times reports:

Ann Coulter was forced to cancel an appearance at the University of Ottawa in Canada in 2010 after about 2,000 students crowded the entrance to the hall at which she was scheduled to speak and protested her views on minorities.

The effect can be similar when schools bow to student demands to disinvite speakers. As Democratic strategist Bob Beckel wrote for USA Today:

Avoiding controversy and "playing it safe" by not inviting — or disinviting — speakers with "controversial" views stifles debate. Most protesters against a speaker usually represent a small minority of the student body. By giving in to protesters, colleges are denying the majority of students their right to hear controversial opinions and drawing their own conclusions about those opinions.

As FIRE President Greg Lukianoff noted in an email to me, disinvitations demonstrate students' decreasing tolerance for hearing opinions different from their own:

[O]n one hand, students have every right to protest or object to a speaker selection for any reason; on the other hand, universities want to show themselves off as institutions that value diverse points of view and function as a marketplace of ideas. Though students do have the right to object to whatever they wish, the apparent increase in the demands that speakers—commencement and otherwise—be disinvited says some very troubling things about student attitudes concerning "hearing the other side."

FIRE believes that students should always answer speech that they don't like with more speech, not censorship. The New York Times relayed this story of students making their views clear while allowing a visiting speaker to do the same:

In 2002, Syracuse students held up their wallets during the commencement speech by Rudolph W. Giuliani, the former mayor of New York City. The wallets were meant to recall Amadou Diallo, an unarmed West African immigrant who was shot 41 times by policemen in 1999 after he reached for his identification.

Students: As your graduation day approaches, continue to share your views regarding your school's visiting speakers. But remember that open debate requires more than one audible voice.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

Trump’s attack on law firms threatens the foundations of our justice system

Executive Watch: Trump’s weaponization of civil lawsuits — First Amendment News 462

The FCC's show trial against CBS is a political power play