Table of Contents

Cassie Conklin is asking questions.

Cassie Conklin used to stuff crumpled up copies of the student newspaper, left for trash, in her shoes.

“The Bottom Line was so lacking that my partner and I would take whole stacks of them to dry our boots.”

But Conklin doesn’t want to disparage the former journalists at Frostburg State University’s independent student reporting outlet.

“I just think there wasn’t a lot of engagement with the newspaper. It’s not like people were coming to the newspaper with tips.”

But that was before she joined.

In the last two years, Conklin’s surge of fresh investigative reporting for The Bottom Line — on topics like police brutality and race, controversial staff layoffs, state audit deficiencies, and the campus’ COVID-19 protocol — has sparked renewed interest in the paper and effected real change in the underserved Appalachian Mountain county where Conklin grew up. It’s one of the poorest counties in Maryland.

But Conklin’s watchdog-style reporting appears to have made her a target for Frostburg administrators facing duelling pressures to preserve the university’s brand: They’re one of the largest employers in a region with record- high unemployment, while also facing numerous controversies amid mammoth declines in enrollment.

Does Frostburg think The Bottom Line is bad for business?

It sure seems that way.

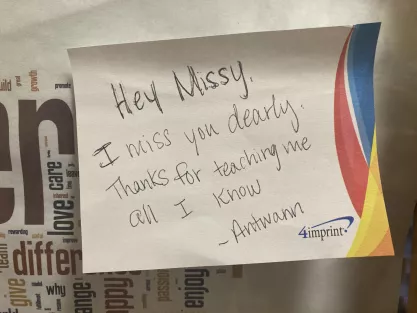

In November, just days after The Baltimore Sun cited Conklin’s critical reporting on the university’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, Frostburg brought her up on harassment charges — saying it discovered video footage of Conklin slipping a threatening note under a staff member’s door during a sit-in protest.

The footage, which the university possessed for a month but only acted on after the Sun report, shows a piece of paper with a sticky note attached falling off a door and coming to rest in the middle of an empty campus hallway.

Some time later Conklin comes along and notices. After pausing to chat with someone nearby, she walks back over to the note, reads the papers, and then re-sticks the note on the door and props the other paper near the door jamb.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=181&v=aCbdF6z172I&feature=youtu.be

Despite the video evidence showing her simply being a nice person, not engaging in harassing behavior whatsoever and, in fact, showing other students engaged in even more blatant note-sliding (and assuming, arguendo, that such behavior could rise to the level of actionable misconduct), Frostburg honed in on only Conklin. Frostburg’s president, Ronald Nowaczyk, also contacted The Bottom Line to demand the independent paper conduct its own investigation into Conklin’s actions.

FIRE and the Student Press Law Center wrote a joint letter to Frostburg with objections to Conklin’s retaliatory treatment, and raising questions about the state of Frostburg’s free press. The next day, administrators assured FIRE they were dropping the investigation.

But Conklin is not celebrating.

Her experience exemplifies troubling nationwide spikes in press censorship as colleges and universities attempt to manage controversies caused by COVID-19, intense political divisions, racial tensions, and more — by hushing them up.

In her last semester, and in a moment when Frostburg’s future is at a crossroads, Cassie Conklin says her investigation has already had a chilling effect on the university’s student press — one that threatens to unravel the progress her tenure at the paper has made.

Daughter of Appalachia

In 2018, Conklin returned to Frostburg State University after a 10-year hiatus. She’d had a marriage, a daughter, a divorce, and was climbing the ranks of a successful career in the restaurant industry. Then one day it simply dawned on her: She had to go back.

“I applied. I enrolled. I was set up for classes before I even told my partner and my daughter. It was just one of those decisions. I was like, ‘I’m going to do it.’”

Armed with a decade more life experience than her peers and a lifetime of dedication to her close-knit community — where she’d made a name for herself over the years fighting outsider elements like fracking and Starbucks — Conklin dove deep into campus life. She set her sights on a geography major, specifically social geography: the study of how a society’s relationships and divisions contribute to things like inequalities.

The area around Frostburg State is rife with those.

Allegany County, which includes the town of Frostburg where Conklin was born and nearby Cumberland where she now lives, is the middle of three counties in the remote Western Maryland panhandle. On a map, it’s the sliver of Appalachian Mountain range wedged between the bulk of West Virginia and Pennsylvania’s southern border. You might have to squint to see it. Just a two-hour drive from international hubs like Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Allegany County is worlds away in most other respects.

An outpost of extreme poverty in a state that’s routinely named the country’s richest, food insecurity, lack of access to education, substance abuse, and some of the highest rates of preventable disease in the nation abound. Life expectancies in Allegany County are among the lowest in Maryland. And at Frostburg State, the area’s lone 4-year institution, which draws students from more diverse nearby cities, Conklin says racial inequality is a unique concern.

“Our campus is located in a really small tight-knit community of about 5,000 people. The town is predominantly white, almost exclusively, in a very rural, Trump-loving, conservative county,” Conklin said. “But then the campus population nearly doubles the population of the town for nine months. And our student body is 48 percent minorities, 30 percent of which are black students.”

The police force there is predominately white, Conklin says, along with almost all of Frostburg’s administration.

“So, there has been some conflict there.” Conklin says “Black students are getting the word out to their friends in D.C. and Baltimore: ‘Don’t go to Frostburg. These people are racist there. And there’s nothing to do.’”

“There’s a lot of work to do to serve the population that they currently serve and to increase the desirability.”

And Conklin, a self-proclaimed “daughter of Appalachia,” takes problems in her little slice of the world personally.

“I think about those things. Day and night. What can we do to make Frostburg State University the best place it can possibly be?”

The Social Geographer

When she returned to campus, Conklin was thinking about life as a geography professor. She found almost immediate success, as part of a team that won the American Association of Geographers national quizbowl. But then she started applying her growing social geography skill set to observations closer to home.

“I was just kind of paying attention. Watching what was going on on campus,” she says. “There are these small pockets of community that have all of these different motivations, different people, different funding sources. There is so much to think about in the campus environment and ecosystem. One of those things was the newspaper.”

“They were covering what the music department was doing, or what the theater department was doing. They were getting that stuff right, but nothing really investigative whatsoever. And just, sometimes pretty poorly written.”

Conklin realized the paper was being underutilized. And that she could do something about it.

“I had this whole epiphany where I was like ‘I’m a student and if I want this newspaper to be better, I can make it better. I can go and I can write. And at least I would feel comfortable that there’d be something worth reading in there.’”

“So, I joined. I started writing.”

Conklin’s first major story turned into a full-fledged police brutality investigation — and got people reading.

Average college reporters might have regurgitated the police blotter, on how authorities broke up a large student gathering with pepper spray, and called it a day. But Conklin doggedly sought witness statements from students who were there and interviewed the chief of police. When the accounts didn’t match up, she sought the responding officers’ body cam footage to see what happened for herself.

Conklin’s instincts that there was more to the story were right on.

“There was a lot in the police conduct that ultimately the chief had to apologize for,” Conklin says. “Her officers were cussing students out and spraying them at close proximity.”

That The Bottom Line was actually getting to the bottom of things that mattered, Conklin says, “got people excited about the newspaper again.” Then they started sending her scoops.

“Someone sent me an anonymous tip about our interim vice president for student affairs and a very dark past that he had.”

That administrator, Jeff Graham, was vying for the permanent placement in his interim role at Frostburg. Acting on the tip she got, Conklin’s November 2019 report detailed Graham’s involvement with child abuse at camps he ran for Department of Juvenile Justice. There were also allegations he was investigated for fraudulent billing practices during a subsequent turn as a social worker. What’s more, Frostburg administrators — including President Nowaczyk — knew about Graham’s mired past when they named him to the position.

“He ultimately withdrew his candidacy,” Conklin says. That was the story that made her realize the impact good reporting can have.

“And then from there that’s what I did. I haven’t written a geography paper in a year.”

The Enemy

It was the Monday before Thanksgiving 2020, with her last finals in sight, that Conklin realized she was in trouble.

“I was starting to pack up for the semester, mentally and emotionally. And we had had a good semester, lots and lots of great articles had come out from The Bottom Line. We had gotten a quick shout out in The Baltimore Sun and The Washington Post, which was a big deal.”

“And I get this very strange text message from our editor-in-chief and the adviser. Looking for contacts for the Student Press Law Center,” Conklin remembers. “They’re like, ‘Yeah it’s just private personnel matters that we’re getting directed on.’”

Then she got her own cryptic email from the vice president for student affairs, saying Conklin had been seen in video footage sliding notes under a staff member’s door.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” Conklin remembers thinking.

Then she called the editor-in-chief.

“And I’m like, ‘This is bullshit. Don’t go down this path with them, you’re going to regret it. They’re strong-arming you. Don’t do it. They don’t have any right to even call you in that room.”

“So, anyway, the next day I go to the meeting with the vice president of student affairs and immediately I defend myself as if I’m in a court of law,” Conklin says. “I haven’t even seen the video footage. I don’t even need to. I just know: I didn’t do it. It doesn’t sound like me. Why would I do that? I didn’t do that.”

Conklin soon realized Frostburg State wasn’t even sure what they were accusing her of.

“They changed their story enough times that I’m kind of realizing ‘I’ve got the upper hand here.’” Conklin had been covering recent free speech controversies at the school from afar and knew her First Amendment rights.

Does Frostburg think The Bottom Line is bad for business? It sure seems that way.

Just days before being investigated herself, Conklin covered Frostburg’s intimidation of resident assistants who were speaking out about the university’s coronavirus response. FIRE, informed by Conklin’s reporting, formally notified Frostburg that its threats to give RAs an “attitude” adjustment for speaking about these issues as students violated the First Amendment.

Reporting on the situation as a journalist, Conklin felt powerless to do more than simply report on what was happening. But now, embroiled in a free speech controversy of her own, Conklin knew she could take action.

“I felt like, actually I can do something here and right now because this can’t stand. It’s happening to me, so I get to advocate for myself. I get to be unapologetically in my own corner and I’m not going to back down.”

Conklin has fears, though, about what other student journalists would have done in her position. And what they will do when she graduates this semester.

“I’m very concerned at the way that the university just feels complete freedom to intimidate writers and editors,” Conklin says. “I’m worried about what the future of the newspaper is, under this university leadership.”

And she questions whether the people in those leadership positions — who would accuse the student newspaper of stirring up trouble, of being “the enemy” — have the same genuine stake in the place as she does.

“When I think about those folks, I don’t think about them as being invested.”

Instead, Conklin wonders if she’s seeing a modern day vestige of the practices that have kept her community trapped in a cycle of poverty for decades. Is Frostburg State University just another lucrative Appalachian resource — like coal and timber — being exploited?

“It is strange that the entire Frostburg administration are people who didn’t grow up here,” Conklin says, noting the huge pay disparity between the university's president and most people in the region. In 2019, President Nowaczyk made $332,000; by contrast, the median income per capita in Allegany County was just over $23,000. "There’s something about those kinds of disparities that frustrate me, because it does feel extractive.”

In that sense, Cassie Conklin is the enemy.

“The newspaper is the enemy to all those with power. We are not supposed to protect the governors. We’re supposed to protect the governed.”

Transparency, and a better future for the people in her community, means everything to Conklin.

“Frostburg has DNA. People have lived there forever who have built this town up. Who really care about it. Who work their whole lives tirelessly to make it run, to make it better.”

“This is what I care about. And everyone who knows me knows that.”

Friday is Student Press Freedom Day, and FIRE is celebrating all week.

Register today for our virtual panel discussion on the state of student journalism.

Student Press Freedom Day 2021: Journalism Against the Odds

Friday, Feb. 26, 2021 | 1:30 PM EST – 2:30 PM EST

In honor of Student Press Freedom Day, join the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) President and CEO Greg Lukianoff and student journalist Cassie Conklin for a keynote address and panel discussion on campus press censorship.

- Press Freedom

- Faculty Rights

- Frostburg State University

- Frostburg State University: Administration Retaliates Against Student Journalist’s Critical Coverage by Dreaming Up Harassment Investigation

- Frostburg State University: RAs Who ‘Bad Mouth’ University’s Response to COVID-19 Face ‘Attitude’ Review

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

Is there a global free speech recession?

Podcast

We travel from America to Europe, Russia, China, and more places to answer the question: Is there a global free speech recession? Guests: - : FIRE senior scholar, global expression - : FIRE senior fellow - : FIRE senior fellow Timestamps: ...

‘Executive Watch’: The breadth and depth of the Trump administration’s threat to the First Amendment — First Amendment News 465

University of Wisconsin academic freedom panel back on after effort to disinvite speaker