Table of Contents

At Yale, Political Expediency Trumps Basic Rights

Last week, The New York Times ran an article on Patrick Witt, the star quarterback at Yale University whose candidacy for a Rhodes scholarship was suspended after the Rhodes selection committee learned of an "informal" complaint of sexual assault lodged against him within Yale's judicial system.

Several days later, Yale released its first-ever "Report of Complaints of Sexual Misconduct," part of Yale's effort to overhaul its handling of sexual misconduct claims. The report provides details both about Yale's various methods for handling such claims (including the "informal complaint" process used by Patrick Witt's accuser) and about the actual claims brought. According to the official press release for the report,

The comprehensive report, which exceeds any legal mandate, provides a level of transparency expected to motivate the Yale community to improve the campus climate, administrators said. It reports all complaints of misconduct, including verbal harassment and sexual assault.

The Witt case and the new Yale report paint a picture of a university more concerned with protecting its reputation and its federal funding (which is threatened by the Department of Education's investigation into Yale's handling of sexual misconduct complaints) than with its students' rights to free speech and due process. KC Johnson has a brilliant piece at Minding the Campus on Yale's handling of the Witt affair. Whomever informed the Rhodes Trust about the allegations against Witt most likely violated Yale's confidentiality rules, but according to Johnson,

[T]here's no sign that Yale has undertaken an investigation as to whether a university employee violated Yale procedures and Witt's due process rights, and an e-mail to Yale's P.R. office asking if such an inquiry was planned went unanswered.

Worse yet, Johnson writes, is what the Witt affair and the Yale report reveal about the state of due process and fundamental fairness at Yale:

[T]he informal complaint procedure's ‘goal is to achieve a resolution that is desired by the [accuser]," so that accusers can ‘regain their sense of wellbeing,' even though the process provides no mechanism for determining whether the accuser is telling the truth. In fact, the process seems all but designed to ensure that the truth won't be discovered, especially if the accuser is less than truthful. According to [the report's author, Deputy Provost Stephanie Spangler], Yale wants the informal complaint procedure to give the accuser ‘choice of and control over the process.' This goal is incompatible with providing due process to the accused.

Yale's report sheds additional light on the problems with Yale's system for handling claims of sexual misconduct. The informal complaint system, by Yale's own admission, "does not include extensive investigation or formal findings." Although Yale reserves the right to override the complainant's wishes and require a formal investigation if it feels there are sufficient "risks to the safety of individuals and/or the community," it appears from the report as if all of the informal complaints were in fact resolved informally, with outcomes typically including restrictions on contact between the parties and counseling for the accused on "appropriate conduct." The contact restrictions and counseling were imposed on the accused students despite the fact that, according to the report, "no determination as to the validity of the allegations was made."

I should hope that if any of the informal complaints involved a credible claim of actual sexual assault, the Yale administration would have indeed pursued an actual investigation, rather than setting a potentially dangerous criminal free in the Yale community with nothing more than some administrative counseling on appropriate behavior. The fact that no such investigations seem to have ensued points at least in part to the fact that Yale, by its own admission, uses "a more expansive definition of sexual assault" than required by law—a definition so expansive that, as KC Johnson notes, "per capita reports of sexual assault on the Yale campus were 10-12 times greater than those in New Haven," which the FBI has rated the fourth most dangerous city in the country.

But as Johnson points out, anyone hearing or reading that a Yale student has been accused of sexual assault is unlikely to be aware of this more expansive definition, causing permanent harm to the reputation of the accused student. And while the identities of parties involved in these informal complaints are supposed to be kept confidential, the Witt case—and Yale's response to it—proves that this is not necessarily the case.

The report also reveals that Yale is investigating students and faculty members for sexual harassment based on allegations of nothing more than "inappropriate comments," in direct violation of the right to free speech promised in Yale's own policies (which provide that "[e]very official of the university ... has a special obligation to foster free expression and to ensure that it is not obstructed.) We already knew (from its decision to discipline the DKE fraternity for crude and tasteless but protected speech) that Yale was willing to throw its commitments to free speech under the bus for political expediency, but it is sad to see that trend continued in this report.

While KC Johnson offers the generous suggestion that Yale's sexual misconduct procedures are part of a well-intentioned but misguided effort to encourage more real victims of assault to step forward, to me the totality of the circumstances here paint a more cynical picture—one of a university far more concerned with its own reputation and financial well-being than with the rights of its students.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

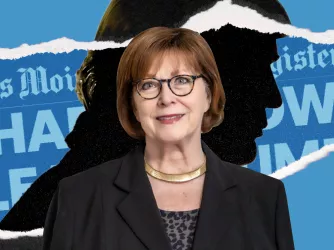

FIRE’s defense of pollster J. Ann Selzer against Donald Trump’s lawsuit is First Amendment 101

Cosmetologists can’t shoot a gun? FIRE ‘blasts’ tech college for punishing student over target practice video

China’s censorship goes global — from secret police stations to video games