Table of Contents

Whether you call it institutional ‘neutrality’ or ‘restraint,’ the Kalven Report is the best way forward

Stephen Lewellyn / University of Chicago Library / Special Collections Research Center

Harry Kalven Jr. delivers a lecture at the University of Chicago

Last week, FIRE, along with the Academic Freedom Alliance and Heterodox Academy, released an open letter urging universities to adopt the principle of institutional neutrality articulated by the University of Chicago’s 1967 Report on the University’s Role in Political and Social Action, also known as the “Kalven Report.” Our letter warns that colleges and universities staking out positions on social or political issues risk “establishing an orthodox view on campus, threatening the pursuit of knowledge for which higher education exists.”

The Kalven Report posits the best way to guard against establishing party lines on campus — and deterring those who disagree from speaking out — is for schools to remain “the home and sponsor of critics,” rather than the critics themselves. This requires committing to “an extraordinary environment of freedom of inquiry and maintain[ing] an independence from political fashions, passions, and pressures.”

Schools like the University of North Carolina System, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Wyoming have already adopted the Kalven Report’s principles, and recent developments show a promising trend among other universities as well. For example, last week the University of Virginia formed a committee to consider institutional neutrality, and on Feb. 2, Columbia University’s University Senate proposed a resolution stating:

The University and its leaders should refrain from taking political positions in their institutional capacity, either as explicit statements or as the basis of policy, except in the rare case when the University has a compelling institutional interest, such as a legal obligation, that requires it to do so.

Not everyone, however, is convinced that neutrality is the right way forward. Joseph Howley, a member of the Columbia University Senate’s committee on faculty affairs, academic freedom, and tenure, distinguishes “neutrality” from “restraint” and argues in favor of the latter. As reported in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

“There’s no language in there about neutrality,” said Howley, a classics professor. “Restraint and neutrality are two different things.”

“Neutrality implies that the institution does not have values,” Howley said. Restraint, on the other hand, simply “implies that the institution is very careful” about taking public positions, he said.

But Howley’s is a distinction without a difference. For one thing, the Kalven Report explicitly acknowledges that universities do, in fact, have values and that there may be occasions when those values are imperiled and require the institution to respond:

From time to time instances will arise in which the society, or segments of it, threaten the very mission of the university and its values of free inquiry. In such a crisis, it becomes the obligation of the university as an institution to oppose such measures and actively to defend its interests and its values.

The Kalven Report’s authors believed a university’s values stem directly from its fundamental purpose, which is to foster “the discovery, improvement, and dissemination of knowledge.” Far from conflicting with these values, institutional neutrality is meant to preserve them, and to further the core mission of our colleges and universities. As the report states:

The neutrality of the university as an institution arises then not from a lack of courage nor out of indifference and insensitivity. It arises out of respect for free inquiry and the obligation to cherish a diversity of viewpoints.

This “respect for free inquiry” and “obligation to cherish a diversity of viewpoints” is why the Kalven Report also strongly advocates for the same “restraint” Howley favors:

These extraordinary instances apart, there emerges, as we see it, a heavy presumption against the university taking collective action or expressing opinions on the political and social issues of the day, or modifying its corporate activities to foster social or political values, however compelling and appealing they may be.

The Kalven Report’s “heavy presumption” against involvement in social or political issues describes a university that is, to use Howley’s words, “very careful” about taking public positions.

The Chronicle notes Columbia University’s resolution was approved but nonbinding. Still, it is a good sign for campus free speech that institutions like Columbia are considering these policies in the first place.

Whether you call it “neutrality” or “restraint,” the point — and the best way forward — is for our institutions of higher learning to adhere to the Kalven Report’s call to “avoid the push and pull of particular political and social commitments.”

Universities have grown too accustomed to putting out political statements — a habit whose costs many schools are now recognizing. From now on the starting point should be guided by institutional neutrality, which will allow universities to return to their core mission of facilitating debate rather than engaging in it.

Learn more about the Kalven Report and why all colleges and universities should adopt institutional neutrality on FIRE’s new Adopting Institutional Neutrality landing page.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

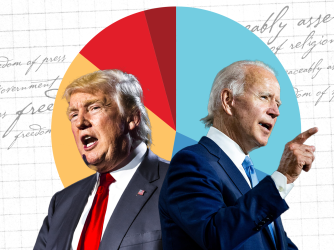

New FIRE poll: Americans equally skeptical Biden or Trump will protect First Amendment rights

Here’s what student journalists need to know about covering campus protests